Laparoscopic Ovarian Surgery

Douglas N. Brown MD, Shaghayegh M. DeNoble MD, Daniel Barraez-Masroua MD, and Farr R. Nezhat MD, FACOG, FACS

Laparoscopic surgery of the ovary can be performed for a variety of indications ranging from simple, benign, and common general gynecological problems to complicated, difficult, or rare pathologies specific to gynecologic oncology or reproductive endocrinology. Although laparoscopic ovarian surgery carries the attendant risks of minimally invasive surgical procedures of the abdomen and pelvis, occasional problems specific to ovarian surgery may arise. We review the utility of and indications for laparoscopic surgery of the ovary as well as specific problems associated with these procedures.

ADNEXAL MASSES

Laparoscopic management of an adnexal mass should be considered the standard treatment for symptomatic, persistent, or high-risk ovarian pathology detected on physical examination and/or radiologic evaluation. The basic technique is well described in detail in the literature.1 Over the last 20 years, compared with laparotomy, laparoscopy has consistently demonstrated decreased blood loss, decreased adhesion formation, less post-operative pain, and shorter hospital stay.2 Although the advantages of managing an ovarian mass laparoscopically are well supported throughout the literature, there remains the uncertainty of encountering a malignancy and consequently performing inadequate staging.

A meta-analysis by Medeiros et al. reviewed laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumors in the nonpregnant patient.1 All 6 studies were randomized controlled trials and included 324 patients. Results showed a longer surgical duration for laparoscopy by 11 minutes. There was a decrease in febrile morbidity; adverse effects, pain, and hospital stay (by 2.79 d) for the laparoscopy patients. One of the studies in this meta-analysis described cost of the interventions. When factoring in hospital stay, the total cost of laparoscopy was significantly lower compared with laparotomy.

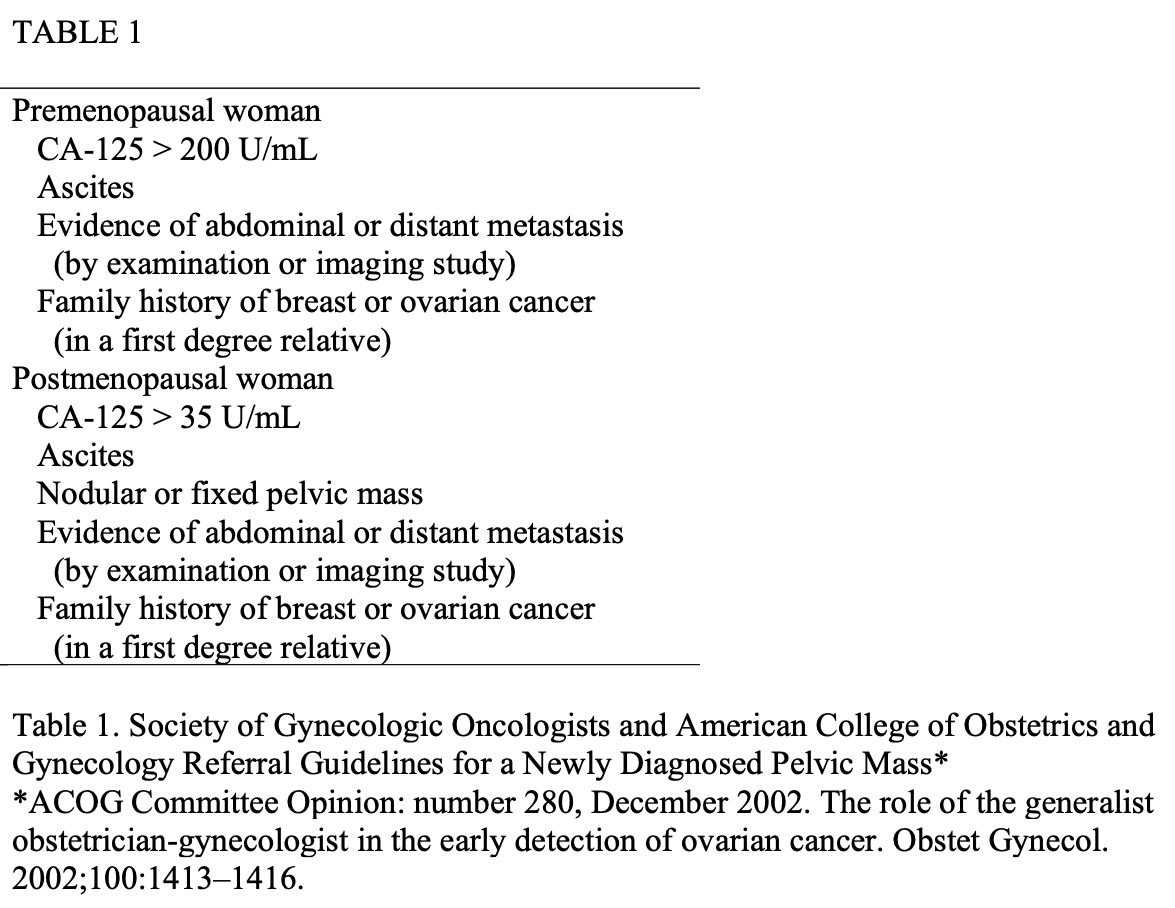

To date, there is no single pre-surgical evaluation, blood test, radiologic evaluation, or algorithm that will absolutely identify an adnexal mass as malignant. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists jointly published referral guidelines for a newly diagnosed pelvic mass to a gynecologic oncologist in 2002 (Table 1). There are numerous studies, however, that clearly demonstrate that after a thorough pre-operative evaluation (clinical exam, radiologic studies, & laboratory values), the relative frequency of encountering a malignancy during laparoscopic evaluation remains very low.3 Nezhat et al. have performed one of the largest studies to date in which 1011 patients underwent laparoscopic management of an adnexal mass.4 Of the 1011 patients, ovarian cancer was discovered intraoperatively in only four. Moreover, their findings indicated that with consistent use of frozen sections of all cyst walls and suspicious tissue, laparoscopic management did not alter the prognosis. Neither CA 125 level, pelvic ultrasonography, nor peritoneal cytologic testing had sufficient diagnostic specificity to predict malignancy. Thus, for the most accurate diagnosis, the surgeon must next be able to laparoscopically evaluate and remove the mass or cyst. Table 1.

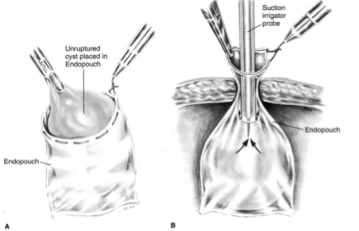

Two to three operative ports are generally utilized to introduce 1 or 2 grasping instruments in addition to an operative instrument that can be utilized to separate the cyst from the remaining ovary. An Endobag or pouch introduced into the pelvis can prevent spillage of cyst contents and is used to remove the specimen without bringing it into contact with the abdominal wall (Figure 1). Successful excision of the cyst and preservation of the ovary depends on the type of pathology encountered as well as the size and location of the portion to be excised, and concurrent oophorectomy and salpingectomy may be indicated and/or necessary.

Figure 1. (A) The unruptured cyst is placed in an Endopouch to prevent spillage of cyst contents and to remove the specimen without bringing it into contact with the abdominal wall. (B) The plastic bag is pulled to the level of the anterior abdominal wall. If the mass is cystic and too large to be pulled through the cannula, a suction-irrigator probe is used to aspirate the cystic fluid. If the excised tissue is solid, it can be cut into pieces or morcellated.

Figure 1. (A) The unruptured cyst is placed in an Endopouch to prevent spillage of cyst contents and to remove the specimen without bringing it into contact with the abdominal wall. (B) The plastic bag is pulled to the level of the anterior abdominal wall. If the mass is cystic and too large to be pulled through the cannula, a suction-irrigator probe is used to aspirate the cystic fluid. If the excised tissue is solid, it can be cut into pieces or morcellated.

Issues that must be considered include the desirability of complete removal of the pathology as well as the potential risks of chemical peritonitis, malignant cell dissemination, and parietal implantation into the laparoscopic port sites from spillage of cyst contents or contact between pathologic tissue and sites in the abdomen and pelvis. In a series of over 500 women who underwent laparoscopic surgery for ovarian cysts, Lok et al encountered cysts that averaged 5.5±2.9 cm in size.5 Endometriomas (44. 5%) and dermoids (24.3%) accounted for over two thirds of the cases, with functional cysts comprising an additional 6.6% of the sample. The pathologic distribution in another large series included, in descending order of frequency, endometriomas, benign adenomas, follicular cysts, corpus luteum cysts, and dermoid tumors.6 In Lok et al’s series, only 5 cases were converted to laparotomy.5 They reported a complication rate of 13% including 5 inferior epigastric vessel injuries, 4 incisional hernias at the 10-mm lateral port site, 2 ureteral injuries, and 1 small bowel injury. In a prospective randomized study, Yuen et al. compared laparoscopy with laparotomy in 100 patients thought to have benign ovarian pathology.7 Regardless of the route of surgery, there was no significant difference in surgical success rate. There was however, a significantly shorter postoperative recovery period noted in the laparoscopy group. These finding was corroborated by Hidlebaugh in a retrospective review of 400 patients who underwent either laparoscopy or laparotomy for ovarian pathology.8

The use of preoperative screening tests has been suggested to reduce the incidence of unexpected malignancy if the tumor markers and ultrasonographic appearance suggest malignancy is present. The negative predictive value of normal testing, however, is not as well established. Moreover, in Nezhat et al’s review of the surgical management of 1011 adnexal masses, they report encountering only 4 ovarian carcinomas noting that preoperative CA-125, sonography, and cytology did not reliably predict malignancy.4 Sadik et al. found 1 ovarian carcinoma and 1 borderline tumor in a series of 220 patients who underwent laparoscopic management of ovarian pathology after preoperative assessment suggested benign pathology.9 Mettler and Semm addressed the evolution of indications for laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy in early and recent reports reviewing several thousand laparoscopic procedures in Kiel, Germany, since the 1970s.10 In 641 ovarian tumors managed between 1992 and 1995, 77% were treated laparoscopically, with preoperative transvaginal, transabdominal, and color Doppler ultrasonography used to classify the ovarian pathology as likely to be benign or potentially malignant. Low-risk features included size 10 cm, small cyst volume, few loculations, thin septa, and echonegative contents. Serum measurement of tumor markers CA-125 and CEA was also obtained. In the low-risk group managed laparoscopically, 98.5% of the pathology was benign, 4 of the 493 tumors were carcinoma, and 4 were borderline tumors. Cysts in this group averaged 4.5 cm compared with 8.2 cm in the laparotomy group; in the laparotomy group, 31% of the 193 tumors were not benign. In the time covered by this group’s work, laparoscopic treatment of ovarian pathology evolved from controversial to the preferred method of evaluation and treatment.

In cases where the pathology is highly likely to be a benign functional cyst or corpus luteal cyst, aspiration can be considered. This treatment is comparatively less likely, however, to prevent recurrence when compared with laparoscopic cyst excision, and is only appropriate for these types of benign findings.11 If it is indicated, a single-port laparoscopic approach may be possible.12,13 With respect to spillage of benign ovarian cyst contents, Berg et al presented the results of 83 cases of dermoid cysts removed laparoscopically.14 In 59 cases, the ovary was preserved, and salpingo-oophorectomy was performed in the remaining 24 cases. Spillage of cyst contents occurred in 66% and 24% of cases, respectively. Nezhat et al. reviewed 81 cases of laparoscopic removal of dermoid cysts, of which 23 included salpingo-oophorectomy.15 Of the 3 techniques utilized, laparoscopy alone, with Endobag, or with colpotomy, spillage occurred least frequently with use of the Endobag (13%) versus laparoscopy alone (62%) and with colpotomy (40%). Their review of other reports of dermoid removal suggested a rate of chemical peritonitis of 0.2%. To prevent this complication after cyst rupture, copious irrigation of the pelvis is strongly advised.

TORSION

Rotation of the adnexa around its vascular pedicle can result in total or partial occlusion of the blood supply, resulting in physical signs and symptoms consistent with an acute abdomen that can potentially progress into a surgical emergency. This is especially common in conjunction with benign neoplastic or functional ovarian cysts.15 Prompt laparoscopic surgical evaluation and treatment is indicated to prevent further damage to the ovary. Descargues et al. reviewed 41 cases of ovarian torsion in women who presented with pain, nausea, vomiting, and a mild leukocytosis.16 Thirteen patients were treated laparoscopically, 11 of whom underwent conservative treatment with detorsion, and 2 with oophorectomy. None of these patients had surgical complications. Shalev and Peleg managed 41 patients with ovarian torsion by laparoscopic rotation of the adnexa, reporting an uneventful recovery postoperatively and return of ovarian function in 14 of the 19 patients.17 Cohen et al. reviewed 58 cases of ovarian torsion in which a blackened, ischemic adnexa was encountered at laparoscopy and managed conservatively.18 Fifty-four of the patients exhibited follicular development on follow-up sonographic imaging of the affected side; 9 showed morphologically normal ovaries seen during subsequent unrelated surgeries; and 4 patients underwent successful in vitro fertilization with oocyte retrieval from the previously ischemic ovary. Oelsner et al. analyzed a total of 102 patients, 67 by laparoscopy and 35 by laparotomy, to determine if the ovary resumes normal function after preservation by simple detorsion only.19 Ninety-three percent of the patients treated by laparoscopy exhibited complete recovery of follicular function assessed by transvaginal ultrasonography, noting significantly less operative complications in the laparoscopic group compared to the laparotomy group. Oelsner et al. also reported in a separate study that 88 to 100% of patients recover ovarian function regardless of the initial appearance of the affected ovary.20

Figure 2. Ovarian torsion.

Figure 2. Ovarian torsion.

In cases of recurrent torsion, oophoropexy, laparoscopic plication of the utero-ovarian ligament, or shortening of the utero-ovarian ligament by an endoloop has been described as a preventive surgical option.21,22,23 Ovarian torsion during pregnancy is a rare condition that has been estimated to occur with a frequency of 1:1000 to 1:5000 pregnancies.24-29 Although the first trimester has been sited as the most common period for ovarian torsion, it may occur in any trimester.24-29

LAPAROSCOPIC OVARIAN SURGERY IN PREGNANCY

While appendectomy and cholecystectomy are the most common surgical procedures performed during pregnancy, the most common gynecologic indication for surgery in a pregnant patient is adnexal pathology.30 The reported incidence of an adnexal mass complicating pregnancy is approximately 1 in 600 pregnancies. Corpus luteal cysts and benign cystic teratomas represent two thirds of cases, whereas malignancy rates range from 2% to 5% in these patients. The main indication for intervention in pregnancy, however, is adnexal torsion.25-28

Hasiakos et al. reported four cases of adnexal mass torsion during pregnancy treated successfully by laparoscopy during the first and second trimester. In each case the pregnancy progressed to term with uneventful deliveries.31 Ovarian torsion has also been reported after successful in vitro fertilization (IVF). Källen reported an ovarian torsion rate of 8 per 10,000 cycles.32 Moreover, Rackow found an incidence of 0.08% to 0.13% ovarian torsion after IVF, noting that patients with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome have an additional increased risk for torsion ranging from 1% to 33%.33

Soriano et al. compared the results of laparoscopy and laparotomy for the management of adnexal pathology in pregnancy, including patients with torsion, pelvic pain, and complex masses, and found no statistically significant difference in fetal outcome between laparotomy and laparoscopy in the first trimester, noting no operative complications in the laparoscopic group.25

The diagnosis of adnexal masses (0.2% to 2.9%) is increasing secondary to increased utilization of first trimester ultrasounds.34 If managed conservatively, 70% to 85% of these masses will resolve as they are functional in nature.34 A retrospective study by Mathevet et al. reviewed 48 laparoscopic procedures in all trimesters over a 12 year period. Indications for surgery included persistent/suspicious ovarian mass, torsion, cyst rupture, and symptomatic pelvic mass.29 For the first 4 years of the study, abdominal entrance was gained by Veress needle placement in the left-upper quadrant. For the last 8 years, entrance was by open technique. There were two conversions to laparotomy for dense adhesions and hemostasis. There was one fetal death at 17 weeks gestation. Three preterm deliveries occurred between 35.5 and 36.5 weeks gestation. These patients had surgery in the first and second trimesters.

Moore and Smith retrospectively reviewed 14 cases of patients with an adnexal mass managed laparoscopically during the second trimester.26 They reported one case of mild peritonitis and one fetal demise at 31 weeks. Stepp et al. performed a similar study involoving 11 cases of laparoscopic adnexal surgery in pregnancy.35 There were no complications, and all patients underwent uneventful deliveries at term.

Yuen et al. reported one of the largest retrospective case series from a single institution. Sixty-seven antepartum patients had laparoscopic removal of adnexal masses in the first and second trimester over a 9-year period.36 Surgeries performed included cystectomy (82.1%), oophorectomy (13.4%), and fenestration (4.5%). All patients in the study underwent an open entry technique with a pneumoperitoneum maintained at 12 mmHg. Two laparoscopies were converted to laparotomy for severe adhesions. There was one fetal demise at 22 weeks. Four of the 67 patients had preterm deliveries, 1 for bleeding placenta previa at 33 weeks, and 3 for preterm labor between 36 and 37 weeks gestation.

Several case reports support laparoscopy in the management of adnexal masses during all trimesters.36 Most authors recommend that open laparoscopic techniques be used on the pregnant patient to prevent injury to the gravid uterus during the introduction of the Veress needle and the potential complication of intrauterine insufflation. One of the surgical goals in pregnancy is minimal manipulation of the uterus to avoid preterm contractions. Laparoscopy does allow this goal with the added benefit of a shorter recovery. Overall these studies show that laparoscopic adnexal surgery can be performed successfully in pregnancy.

FERTILITY

In the field of reproductive endocrinology, laparoscopic drilling of the ovary has been utilized to treat women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) by resecting cystic ovarian tissue in an effort to restore normal cyclic ovarian function (Figure 3). Generally, a 3-puncture technique is utilized, with a grasper and either a diathermy needle or intraperitoneal laser introduced through the 2 operative ports.38-41 Laparoscopic wedge ovarian resection has been reported as an alternative. Duleba et al. performed a prospective analysis and reported that 67% of their patients who underwent laparoscopic ovarian wedge resection became pregnant within 4.9 months of the surgical intervention.42 There is also a theoretical risk of premature ovarian failure from aggressive wedge resection of healthy ovarian tissue. This has not been encountered, however, in long-term follow-up studies of patients who have undergone this procedure.43

Figure 3. Ovarian surface after drilling CO2 laser.

Figure 3. Ovarian surface after drilling CO2 laser.

Farquhar et al., performed a retrospective analysis of 16 separate trials comparing medical therapy versus laparoscopic ovarian drilling in patients with clomiphene-resistant PCOS.44 The authors reported no differences in the rate of live birth, clinical pregnancy, or spontaneous miscarriage between the two groups. Of note, laparoscopic ovarian drilling decreased the risk of multiple gestation from 16% (with gonadotropins alone) to 1%. Malkawi et al., in a recent series, found equivalent results when comparing medical management of PCOS with laparoscopic ovarian drilling.45 Pirwani and Tulandi reported similar results but recommend that surgery should be utilized only when medical therapy proves unsuccessful.46

Several studies allude to an inherent risk of postoperative adhesion formation after laparoscopic ovarian drilling with rates ranging from 19% to 43%.47-49 Mercorio et al., performed a randomized prospective study to determine the incidence, site, and grade of ovarian adhesion formation after laparoscopic ovarian drilling and analyze the association between the number of punctures made and the incidence and grade of adhesions.50 Adhesion formation was detected in 54 of the 90 women (60%) and in 83 of the 180 ovaries treated (46%). There was a statistically significant increase in dense adhesion formation associated with the left ovary as opposed to the right ovary independent of the number of ovarian punctures performed. The authors concluded that although the incidence of ovarian adhesion formation after laparoscopic ovarian drilling was high, the number of ovarian punctures performed did not influence the extent and severity.

PROPHYLAXIS

In patients at high risk of developing ovarian carcinoma due to hereditary factors, prophylactic oophorectomy has been advocated. Patients with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations or with familial Lynch syndrome II are at an increased risk of developing ovarian carcinoma; with lifetime risks approaching 45%, 25%, and 10% respectively.51,52 Although patients with these mutations remain at risk for developing primary peritoneal cancer, prophylactic oophorectomy at the conclusion of childbearing should be strongly considered (Figure 4).53 Kauff et al. prospectively studied 170 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations over a 6- year period, who underwent either surveillance or prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, finding a substantially decreased risk of breast and ovarian carcinoma (RR = 0.25) in the oophorectomy group;54 concurrently, Rebeck et al. prospectively studied over 250 patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who underwent prophylactic oophorectomy, comparing them with matched controls under observation.55 They found significant reductions in the rate of coelomic epithelial cancer (RR = 0.04) and breast cancer (RR = 0.47) in the surgical group. Leeper et al. noted a high rate of occult malignancy (17%) in high risk women who underwent prophylactic laparoscopic oophorectomy and salpingectomy.56 Seventy patients with breast disease had laparoscopic oophorectomy between January 2000 and June 2007. Willsher et al. retrospectively reviewed forty-three patients whom had laparoscopic oophorectomy for adjuvant endocrine treatment of early breast cancer, 13 for prophylaxis, 7 for endocrine and prophylactic reasons and 7 for treatment of metastatic breast cancer.57 Sixteen of the patients underwent laparoscopic oophorectomy and breast surgery at the same time. Of note, four BRCA mutation carriers had prophylactic mastectomies, bilateral breast reconstruction, and bilateral laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy. No patient required conversion to an open procedure, including 29 patients with previous abdominal surgery. There were no significant complications. The authors conclude that breast oncological and/or reconstructive surgery and prophylactic laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy can be reliably carried out as a combined procedure.

Figure 4

*Cho JE, Liu C, Gossner G, Nezhat FR. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;52(3):313-26.

*Cho JE, Liu C, Gossner G, Nezhat FR. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;52(3):313-26.

ONCOLOGY

Management of gynecologic cancers or suspicious masses should be performed utilizing the principles of oncologic surgery.58-60 Although still in its infancy, laparoscopy is perhaps the most valuable tool for evaluating the operability, either primarily or at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery. It should therefore be used to triage candidates for either 1) initial optimal cytoreduction, or for 2) neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Borderline ovarian tumors represent 10% to 20% of epithelial ovarian cancers and typically have an excellent prognosis. The incidence of borderline tumors is predominantly among reproductive age patients. Fertility-sparing options may range from cystectomy to adnexectomy. Laparoscopic staging in borderline ovarian tumors has become increasingly common with advances in endoscopic techniques and instruments. The first case reports of laparoscopic treatment in borderline ovarian tumor were reported by Reich et al. and Nezhat et al.61,62 Subsequently, multiple case series studies have emerged to further evaluate the clinical outcomes and feasibility of laparoscopic treatment of borderline ovarian tumors. The largest case series to date was conducted by Fauvet et al. in which 107 patients underwent the laparoscopic treatment of borderline ovarian tumors.63 The mean follow-up was 27.5 months with 100% survival and only 4 with evidence of disease. Thus, to date, the preliminary data regarding borderline ovarian tumors suggest that laparoscopic management of borderline ovarian tumors is a feasible and efficacious approach.

Early-stage invasive ovarian cancer requires complete surgical staging to obtain important prognostic information, avoid understaging of patients, and dictate postoperative management. This traditionally involves total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, peritoneal biopsies, pelvic and para- aortic lymph node dissection, and peritoneal washings. If complete staging was not performed at the initial time of diagnosis, a restaging procedure that may be accomplished through laparoscopy or laparotomy is typically recommended to stage these patients. Nezhat et al. reported the longest mean follow-up in a case series of 36 patients with an invasive ovarian carcinoma managed with laparoscopic staging/restaging.64 Mean duration of followup time was 55.9 months, and there was a demonstrated 100% overall survival rate. Importantly, this study had the largest number of primary staging procedures. Few retrospective case series have compared laparoscopy to laparotomy regarding the feasibility and overall outcomes. Chi et al. conducted a case control study of staging in early ovarian cancer with 20 patients staged by laparoscopy compared with 30 patients staged by laparotomy.65 There were no differences in the omental specimen size or number of lymph nodes obtained. Blood loss and hospital stay were lower for the laparoscopy group, but the operating time was longer. There were no conversions to laparotomy or other intraoperative complications in the laparoscopy group. It was concluded that laparoscopic staging of early ovarian cancers appears to be feasible and comprehensive without compromising survival when performed by gynecologic oncologists experienced with advanced laparoscopy.

Owing to the rarity of early ovarian cancer, diagnosis and challenges with preoperative diagnosis, a randomized control trial has not been feasible. Alternative evaluations of accuracy can be inferred by comparing upstaging rates between laparoscopic and laparotomy cases. The feasibility of laparoscopic completing surgical staging in patients with incompletely staged ovarian, fallopian tube, endometrial, and primary peritoneal cancers was demonstrated in the GOG protocols 9302 and 9402.66 Fifty-eight patients underwent complete laparoscopic staging, confirmed with photographic documentation. Nine patients were incompletely staged laparoscopically due to the lack of peritoneal biopsies, cytology, or bilateral lymph nodes. Seventeen patients underwent laparotomy. In comparing patients who managed laparoscopically with those managed with laparotomy, the laparoscopic group demonstrated a significantly less blood loss, hospital stay, and Quetlet index and also comparable nodal yields.

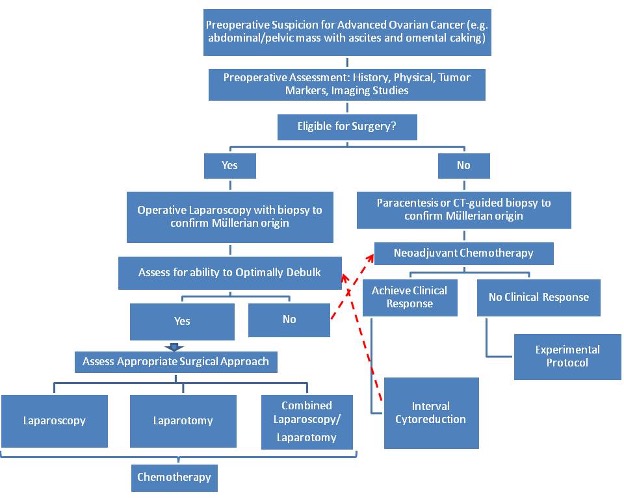

As the use of laparoscopy has increased in gynecologic oncology, 3 applications in advanced ovarian cancer have emerged in the literature: a triage tool for resectability, second look evaluation, and select cases of primary or recurrent cytoreduction. In Figure 4, we have outlined a potential algorithm to incorporate the current applications of laparoscopy in the management of advanced ovarian cancer.

A review of the current literature suggests that survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval cytoreductive surgery does not differ significantly from those treated with primary debulking surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy. The challenges to this approach include the limitations of current tools such as CA- 125 and computed tomography scanning to predict respectability. Laparoscopy has been demonstrated to have a higher sensitivity than these other tools. Vergote et al. reported a series of 285 patients using open laparoscopy to determine whether the patient could be optimally debulked.67 They found a 96% accuracy of resectability. Fagotti et al. described 64 patients that underwent laparoscopy followed by immediate laparotomy and compared the intraoperative impressions.68 They found that no patients deemed unresectable on laparoscopy were found to be candidates for optimal debulking on subsequent laparotomy, yielding a negative predictive value of 100%. In fact, 87% of patients categorized as resectable on the laparoscopic assessment were optimally debulked.

The second-look procedure consists of a systematic pathologic assessment of the abdominal/pelvic cavity in a patient who is clinically without evidence of disease after the completion of primary staging and frontline chemotherapy. Although controversial in the clinical setting of ovarian carcinoma, this procedure can provide important prognostic information for the patient and represents the most accurate method to evaluate the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy protocols.

Littell et al. conducted a study directly comparing second-look laparoscopy with laparotomy evaluations.69 This study consisted of 70 patients who underwent second-look laparoscopy with a plan for immediate laparotomy if the laparoscopic impression was negative for disease. The authors found that a negative second-look laparoscopy with negative cytology carries a 91.5% prediction of negative laparotomy. Laparotomy was associated with a higher morbidity including small bowel injuries, small bowel obstruction, fever, cardiac ischemia, wound cellulites, and pneumonia. The laparoscopy only group had 3 vaginal cuff dehiscences intraoperatively during vaginal preparation before the initiation of surgery. No other complications intraoperatively or postoperatively were noted. Thus, although laparotomy may offer a small increase in sensitivity and negative predictive value, this study concluded that it does not warrant the increased morbidity.69

To date, limited studies have been published describing laparoscopic advanced ovarian cancer debulking. Amara et al. first reported a small case series that included complete laparoscopic management of advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer.70 In this series, 3 patients underwent primary staging or cytoreductive procedures to yield stages IA, IIA, and IC malignancies. Four cases of second-look laparoscopy with interval debulking were performed. All patients did well postoperatively with 1 patient who expired due to recurrent disease declining further intervention. Nezhat et al. reported their experience in laparoscopic primary and secondary debulking for advanced ovarian cancer.71 The study evaluated 32 patients who were subdivided into 2 groups: group 1 consisted of 13 patients who underwent primary cytoreduction, and group 2 consisted of 19 patients who underwent secondary/tertiary cytoreduction. Operative time and mean blood loss in group 1 compared with group 2 were 277 minutes and 240 mL, and 191 minutes and 126 mL, respectively. No patient required blood transfusion or developed subsequent port-site metastases. In group 1, after 13.7 months of mean follow-up, 2 patients had expired, 9 patients were alive with no evidence of disease and 2 patients were alive with disease. In group 2, after 26.9 months mean follow-up, 6 patients had expired, 10 patients were alive with no evidence for disease and 3 patients were alive with disease. Although these results are encouraging and the role of laparoscopy in managing advanced ovarian cancer will continue to expand, more long-term studies are needed to fully appreciate the role of this technology in advanced ovarian cancerstaging.

Several main concerns have limited the widespread use of laparoscopy in ovarian cancer: the potential for inadequate staging, tumor cell peritoneal dissemination with carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum, possibly a higher incidence of cyst rupture, and port-site metastases.

Inadequate staging may occur in cases with low-intraoperative suspicion for malignancy, not performing or inaccurate frozen section evaluation, or in institutions in which gynecologic oncology support may be limited. However, in cases where frozen section confirms cancer (and in the appropriately consented patient), complete laparoscopic staging should be possible in the hands of an experienced gynecologic oncologist.

The adverse effect of cyst rupture in laparoscopy and laparotomy approaches is conflicting. Currently, the largest study addressing the effect of cyst rupture consists of a retrospective, multicenter study of over 1500 patients. Vergote et al. found that a cyst or mass rupture was an independent predictor of disease-free survival.72 However, this study is limited as a majority of patients had incomplete staging procedures, which may influence disease-free survival. In contrast, Sjövall et al. found no difference in survival among a retrospective review of 394 patients.73 An additional confounding variable is the use of iatrogenic controlled cyst decompression. These techniques may include a controlled drainage of the mass while contained in the endoscopic bag to prevent spillage. Importantly, studies that compare tumor rupture rates do not account for those that may have occurred in such a controlled manner. Regardless of these study limitations, one should aim to maintain oncologic principles and avoid spillage of cancer cells during the extraction of an ovarian mass.

Port-site metastases have been largely reported as case reports in the literature for both borderline and early invasive pathologies. The etiology of port-site metastases is uncertain. Several hypotheses include tumor cell entrapment, direct spread from instrumentation, direct spread from the trocar in which instruments are exchanged, and the “chimney effect,” which suggests that tumor cells travel along the sheath of the trocars with the leaking gas.

In cases of borderline ovarian tumors, only a few cases of port-site metastases have been reported. Of the 9 reported cases, surgical excision was performed with a 100% overall survival at 6 to 72 months follow-up.74 In contrast, invasive ovarian cancer has port-site metastases reported in up to 16% of cases. In one study, the risk of port-site metastases was highest (5%) in patients with recurrence of ovarian or primary peritoneal malignancies undergoing procedures in the presence of ascites.75 The overall prognosis has not been affected with these metastatic lesions as they tend to respond to chemotherapy without relapse. In fact, one study reported no survival differences among port-site metastases patients compared with no port-site metastases patients.76 Techniques that may minimize the likelihood of port-site metastases include removal of an intact specimen and layered closure of the trocar sites.77,78

When advanced pelvic cancers require radiation therapy, laparoscopic ovarian surgery may be indicated to preserve ovarian function in women of reproductive age.

Laparoscopic oophoropexy can be performed in patients who will receive radiotherapy to the abdomen and who may wish to preserve fertility. Potential sites for repositioning include the pelvic sidewall, paracolic gutters, base of the round ligament, and lower pole of the right kidney. Typically, division of the utero-ovarian ligament is followed by dissection of the mesosalpinx and lateral traction on the freed ovary. Suspension sutures are then placed through the ovary and peritoneum to fix the ovary into position away from the radiation field. A recent case report by Visavanathan et al. describes endoscopic suturing of the ovary to the round ligament without disrupting the ovarian ligament or the tubo-ovarian relationship, permitting a return to normal tubo-ovarian function after the sutures are divided.79 Clough et al. prospectively studied 20 patients who had successful laparoscopic suspension of the ovary into the right paracolic gutter prior to undergoing pelvic radiotherapy, with 100% success in preservation of ovarian function in the patients under 40 years of age.80 A review of laparoscopic reports of oophoropexy by Bisharah and Tulandi describes an overall success rate of 88.6%.81

RARE INDICATIONS

Ovarian pregnancy is an uncommon form of ectopic pregnancy; published reports exist of laparoscopic oophorectomy performed to treat this condition.82-83

SUMMARY

Laparoscopic surgery of the ovary has several distinct advantages over laparotomy, has been shown to be safe and effective, and can be performed for a variety of indications ranging from simple, benign, and common general gynecological problems to more complicated, difficult, or rare pathologies specific to gynecologic oncology and reproductive endocrinology. The role of laparoscopy in advanced ovarian, fallopian, and primary peritoneal cancers is 1) to rule out benign and non-Müllerian malignancies, and 2) to assess the extent of resectability either by laparoscopy or laparotomy, or the need for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cytoreduction. The algorithm in Figure 4 may be used as a guide in future studies to evaluate the continuously expanding role of laparoscopy in patients with ovarian, fallopian, and primary peritonealcancers.

References

- Medeiros LR, Stein AT, Fachel J, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:387–399.

- Nezhat CR, Nezhat FR, Metzger DA, Luciano AA. Adhesion reformation after reproductive surgery by videolaseroscopy. Fertil Steril. 1990 Jun;53(6):1008-11.

- Whiteside JL, Keup HL. Laparoscopic Management of the ovarian mass: A practical approach. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;53(3):327-334.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, welander CE, et al. Four ovarian cancers diagnosed during laparoscopic management of 1,011 adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:790.

- Lok IH, sahota DS, Rogers MS, Yuen PM. Complications of Laparoscopic surgery for benign ovarian cyst. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000; 7(4): 529-534.

- Mettler L, Semm K Shiver K. Endoscopic management of adnexal masses. JSLS. 1997;1:103-112.

- Yuen PM, Yu KM, Yip SK, Lau WC, Rogers MS, chang A.A. randomized prospective study of laparoscopy and laparotomy in the management of benign ovarian masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177: 109-114.

- Hidlebaugh Da, Vulgaropulos S, Orr RK, treating adnexal masses. Operative laparoscopy vs. laparotomy. J Reprod Med. 1997;42(9): 551-558.

- Sadik S, Onoglu AS, Gokdeniz R, Turan E, Taskin O, Wheeler JM.Laparoscopic management of selected adnexal masses. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999; 6(3): 313- 316.

- Mettler L, Semm K, endoskopiche operationsmöglichkeiten beim corpus-und ovarial-karzinom. Geburtsh Gynäkol Deutschland Frankreich. 1994;8:39-40.

- Marana R, Caruana P, Muzii L, Catalano GF, Mancuso S. Operative laparoscopy for ovarian cyst. Excision vs. aspiration. J reprod Med. 1996;41(6): 435-438.

- Kosumi T, Kubota A, Usui N, Yamauchi K, Yamasaki M, Oyanagi H. Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy using a single umbilical puncture method. Sug Laparosc endosc Percutan tech. 2001;11(1):63-65.

- Eltabbakh GH, Kaiser JR, Laparoscopic management of a large ovarian cyst in an adolescent. A case report. J reprod Med. 2000;45(3):231-234.

- Berg C, Berndorff U, Diedrich K, Malik E. Laparoscopic management of aovarian dermoid cyst.A series of 83 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;266(3):126-129.

- Nezhat CR, Kalyoncu S, Nezhat CH, Johnson E, Berlanda N, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic management of ovarian dermoid cyst: ten years’ experience. JSLS. 1999; 3 (3): 179-184.

- Descargues G, Tinlot-Mauger F, gravier A, Lemoine JP, Marpeau Adnexal torsion: a report on forty-five cases. Eur J Obtet gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98(1):91-96.

- Shalev E, Peleg D.Laparoscopic treatment of adnexal torsion. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176(5):448-450.

- Cohen SB, Oelsner G, Seidman DS, Admon D, Mashiach S, Goldenberg M. Laparoscopic detorsion allows sparing of the twisted ischemic adnexa. J Am Assoc gynecol laparosc. 1999;6(2):139-143.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003 Dec;18(12):2599-602.

- Oelsner G, shashar D. Adnexal torsion. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep; 49(3): 459- 63.

- Germain M, Rarick T, Robins E.Management of intermittent ovarian torsion by laparoscopic oophoropexy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(4 pt 2):715-717.

- Righi RV, McComb PF, Fluker MR. Laparoscopic oophoropexy for recurrent adnexal torsion. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(12):3136-3138.

- Weitzman VN, DiLuigi AJ, Maier DB, Nulsen JC. Prevention of recurrent adnexal torsion. Fertil Steril. 2008 Nov;90(5):2018.

- Bassil S, Steinhart U, Donnez J. Successful laparoscopic management of adnexal torsion during week 25 of a twin pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1999; 14: 855–857.

- Soriano D, Yefet Y, Seidman D, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:955–960.

- Moore RD, Smith WG. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnant women. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:97–100.

- Akira S, Yamanaka A, Ishihara T, et al.Gasless laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy during pregnancy: Comparison with laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:554– 557.

- Mashiach S, Bider D, Moran O, et al. Adnexal torsion of hyperstimulated ovaries in pregnancies after gonadotropins therapy. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:76–80.

- Mathevet P, Nessah K, Darget D, Mellier G. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003; 108: 217–222.

- Condous, A. Khalid, E. Okaro and T. Bourne, Should we be examining the ovaries in pregnancy? Prevalence and natural history of adnexal pathology detected at first-trimester sonography, Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:62–66.

- Hasiakos D, Papakonstantinou K, Kontoravdis A, Gogas L, Aravantinos L, Vitoratos N.Adnexal torsion during pregnancy: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008 Aug;34(4 Pt 2):683-7.

- Källén B. Maternal morbidity and mortality in in-vitro fertilization. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008 Jun;22(3):549-58.

- Rackow BW, Patrizio P. Successful pregnancy complicated by early and late adnexal torsion after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2007 Mar;87(3):697.

- Kilpatrick CC, Monga M. Approach to the acute abdomen in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin NorthAm. 2007;34:389–402.

- Stepp KJ,Tulikangas PK, Goldberg JM,Attaran M, Falcone T. Laparoscopy for adnexal masses in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(1):55-59.

- Yuen PM, Ng PS, Leung PL, et al. Outcome in laparoscopic management of persistent adnexal mass during the second trimester of pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1354-1357.

- Jackson H, Granger S, Price R, et al.Diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of surgical diseases during pregnancy: an evidence-based review. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1917–1927.

- Gjonnaess H. Polycystic ovarian syndrome treated by ovarian electrocautery through the laparoscope. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:20-25.

- Li TC, Saravelos H, Chow MS, Chisabingo R, Cooke ID. Factors affecting the outcome of laparoscopic ovarian drilling for polycystic ovarian syndrome in women with anovulatory infertility. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(3):338-344.

- Kovacs G, Buckler H, Bangah M, et al.Treatment of anovulation due to polycystic ovarian syndrome by laparoscopic ovarian electrocautery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:30-35.

- Keckstein G, Rossmanith W, Spatzier K, Schneider V, Borchers K, Steiner R. The effect of laparoscopic treatment of polycystic ovarian disease by CO2-laser or Nd:YAG laser. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:103-107.

- Duleba AJ, Banaszewska B, Spaczynski RZ, Pawelczyk L. Success of laparoscopic ovarian wedge resection is related to obesity, lipid profile, and insulin levels. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(4):1008-

- Amer SA, Gopalan V, Li TC, Ledger WL, Cooke ID. Long term follow-up of patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome after laparoscopic ovarian drilling: clinical outcome. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(8):2035-2042.

- Farquhar C, Lilford RJ, Marjoribanks J, Vandekerckhove P.Laparoscopic ‘drilling’ by diathermy or laser for ovulation induction in anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD001122.

- Malkawi HY,Qublan HS, Hamaideh AH. Medical vs. surgical treatment for clomiphene citrate-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23(3):289-293.

- Pirwany I, Tulandi T. Laparoscopic treatment of polycystic ovaries: is it time to relinquish the procedure? Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):241-251.

- Gurgan T, Urman B. Adhesions after ovarian drilling and intercede. Fertil Steril. 1994;2:424-426.

- Saravelos H, Li TC. Post-operative adhesions after laparoscopic electrosurgical treatment for polycystic ovarian syndrome with the application of Interceed to one ovary: a prospective randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:992-997.

- Gurgan T, Kisnisci H,Yarali H, Develioglu O, Zeyneloglu H, Aksu T. Evaluation of adhesion formation after laparoscopic treatment of polycystic ovarian disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:1176- 1178,

- Mercorio F, Mercorio A, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Barba GV, Pellicano M, Nappi C.Evaluation of ovarian adhesion formation after laparoscopic ovarian drilling by second-look minilaparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 2008 May;89(5):1229-33.

- Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424-428.

- Burke W, Petersen G, Lynch P, et al. Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. I. Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cancer Genetics Studies Consortium JAMA. 1997;277(11):915-919.

- Swisher E. Prophylactic surgery and other strategies for reducing the risk of familial ovarian cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4(2):105-110.

- Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1609-1615.

- Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616-1622.

- Leeper K, Garcia R, Swisher E, Goff B, Greer B, Paley P. Pathologic findings in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens in high-risk women. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87(1):52-56.

- Peter Willsher,*† Ahmad Ali and Lee Jackson. Laparoscopic Oophorectomy in the managmanet of breast disease. ANZ J surg. 2008;78:670-672.

- Cho JE, Liu C, Gossner G, Nezhat FR. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;52(3):313-26.

- Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176-182.

- Argenta PA, Nezhat F. Approaching the adnexal mass in the new millennium. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(4):455-471.

- Reich H, McGlyn F, Wilkie W. Laparoscopic management of stage I ovarian caner: a case report. J Reprod Med. 35:601–604.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Burrell M. Laparoscopically-assisted hysterectomy for the management of a borderline ovarian tumor: a case report. J Laparoendosc Surg. 2:167– 169.

- Fauvet R, Boccara J, Dufournet C, et al. Laparoscopic management of borderline ovarian tumors: results of a French multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:403–410.

- Nezhat F, Ezzati M, Rahaman J, et al. Laparoscopic management of early ovarian and fallopian tube cancers: surgical and survival outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:83.e1–83.e6.

- Chi DS, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, et al. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgical staging of apparent stage I ovarian and fallopian tube cancers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1614–1619.

- Spirtos NM, Eisekop SM, Boike G, et al. Laparoscopic staging in patients with incompletely staged cancers of the uterus, ovary, fallopian tube and primary peritoneum: a gynecologic Oncology group(GOG) study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005193:1645-1649.

- Vergote I, De Wever I, Tjalma W, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary debulking surgery in advanced ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 285 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:431–436.

- Fagotti A, Fanfani F, Ludovisi M, et al. Role of laparoscopy to assess the chance of optimal cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer: a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:729–735.

- Littell RD, Hallonquist H, Matulonis U, et al. Negative laparoscopy is highly predictive of negative second-look laparotomy following chemotherapy for ovarian, tubal and primary peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:570–574.

- Amara DP, Nezhat C, Teng NN, et al. Operative laparoscopy in the management of ovarian cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6:38–45.

- Nezhat FR, Datta MS, Lal N, et al. Laparoscopic cytoreduction for primary advanced or recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:S60.

- Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176–182.

- Sjövall K, Nilsson B, Einhorn N. Different types of rupture of the tumor capsule and the impact on survival in early ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994;4:333.

- Morice P, Camatte S, Larregain-Fournier D, et al. Port-site implantation after laparoscopic treatment of borderline ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1167– 1170.

- Nagarsheth NP, Rahaman J, Cohen CJ, Gretz H, Nezhat F. The incidence of port-site metastases in gynecologic cancers. JSLS. 2004;8:133-9.

- Vergote I, Marquette S, Amant F, Berteloot P, Neven P. Port-site metastases after open laparoscopy: a study in 173 patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Int K Gynecol Caner. 2005;15(5):776-779.

- Ramirez PT, Wolf JK, Leveback C. Laparoscopic port-site metastases: etiology and prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:179–189.

- Van Dam PA, DeCloedt J, Tjalma WA, Buytaert P, Becquart D, Vergote Trocar implantation metastasis after laparoscopy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: can the risk be reduced? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:536–41

- Visvanathan DK, Cutner AS, Cassoni AM, Gaze M, Davies MC.A new technique of laparoscopic ovariopexy before irradiation. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(5):1204-1206.

- Clough KB, Goffinet F, Labib A, et al. Laparoscopic unilateral ovarian transposition prior to irradiation: prospective study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1996;77(12):2638-2645.

- Bisharah M,Tulandi T. Laparoscopic preservation of ovarian function: an underused procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):367-370.

- Sijanovic S,Topolovec Z, Sijanovic I. Laparoscopic treatment of primary ovarian pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(2):221-222.

- Erenus M, Gokaslan H, Ozer K. Successful laparoscopic treatment of a ruptured primary ovarian pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(1):87-88.