Laparoscopic Management of Suspicious Adnexal Masses

Bulent Berker, MD, Emre Goksan Pabuccu, MD

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian neoplasms are one of the most common pathologies among women of all age groups. The prevalence of adnexal masses differs according to their clinical manifestations. It has been estimated that 5% to 10% of women in the United States will undergo a surgical procedure owing to a suspected ovarian mass during their lifetime, and 13% to 21% of these women will suffer from malignancy.1 Up to 300 000 women are hospitalized each year for evaluation of an adnexal mass. The majority of these patients undergo surgery. The prevelance of adnexal masses is 0.17% to 5.9% in asymptomatic and 7.1% to 12% in symptomatic patients.2

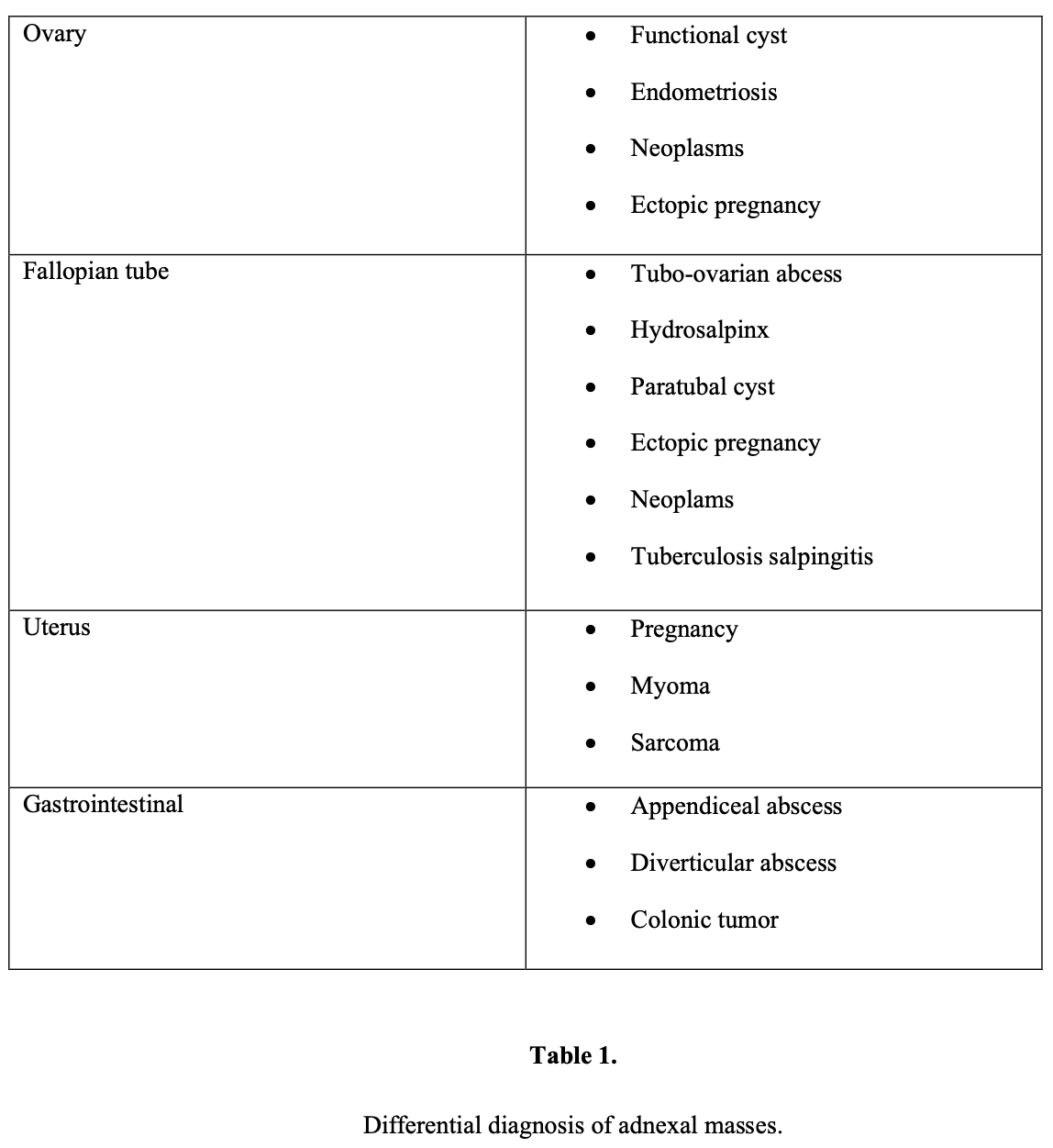

Adnexal mass refers not only to ovarian abnormalities but also to masses originating in the fallopian tube, uterus, bowel, urinary system, and retroperitoneum.

The clinical evaluation of an adnexal mass should focus on determining whether the mass is benign or malignant and whether the mass can be removed without any complications.

No single test is available to evaluate these parameters; therefore, age, history, symptoms, physical examination, laboratory findings, and diagnostic imaging should be important 6- step evaluation parameters before the management of an adnexal mass in every age group.

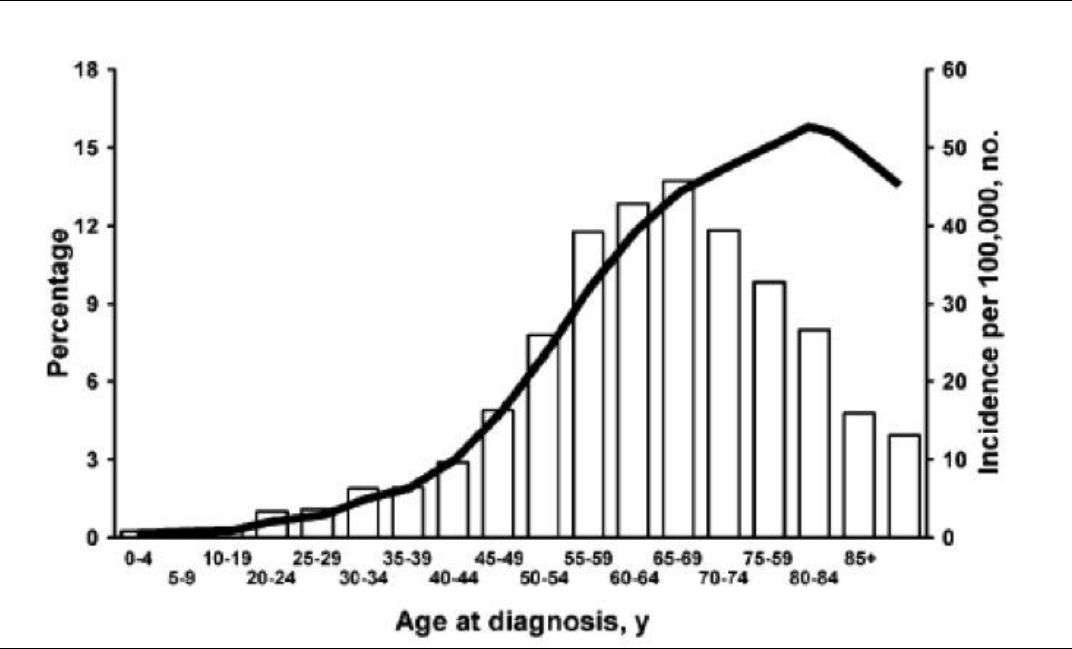

Figure 1. Malignant lesions are more common in the postmenopausal age group.

Figure 1. Malignant lesions are more common in the postmenopausal age group.

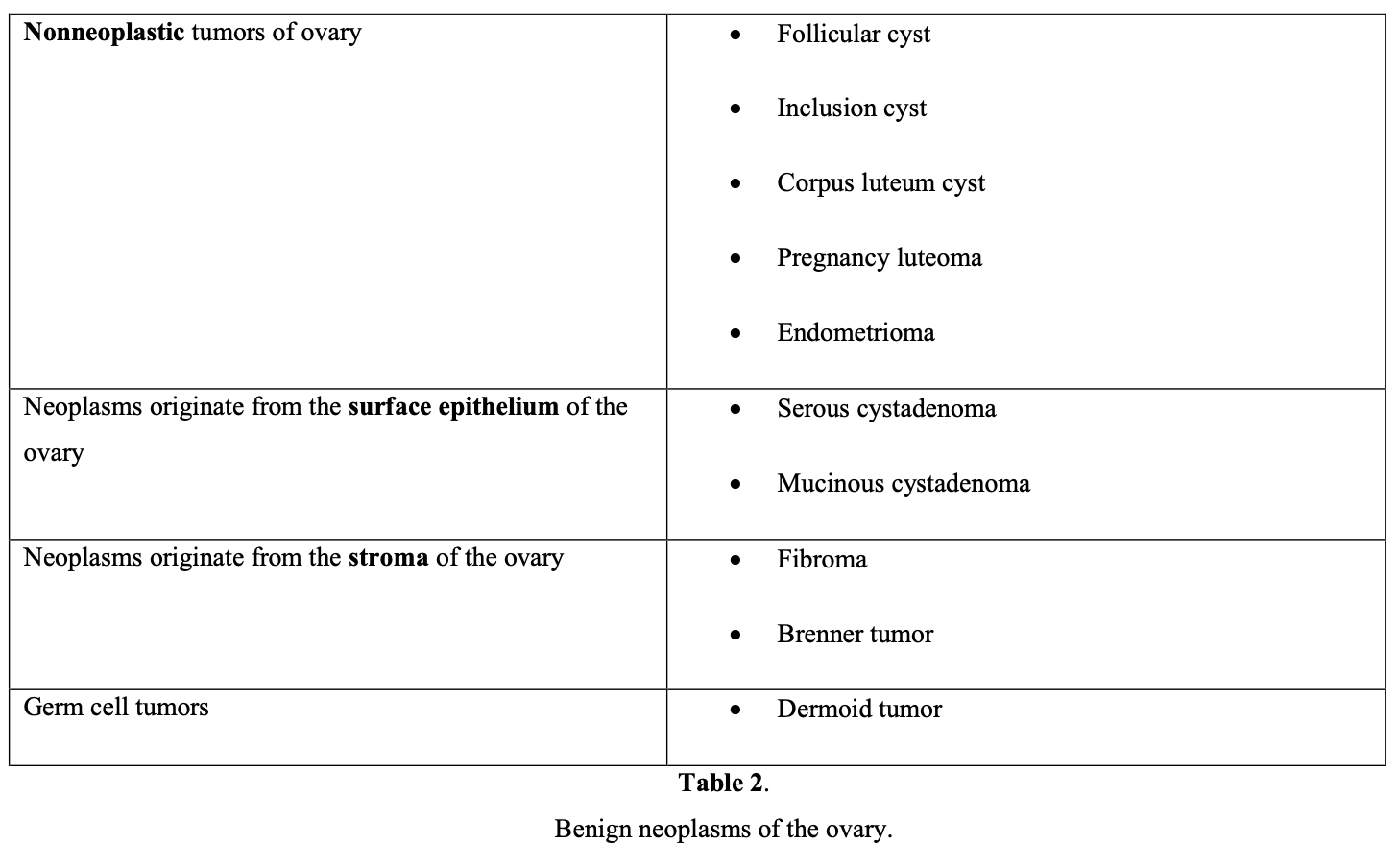

Large series reported that the vast majority of adnexal masses (80%) seen in women under age 55 are hormone dependent, such as functional cysts and endometriomas; approximately 8% are benign neoplasms, such as teratomas, cystadenomas, and leiomyomas; and 0.4% are malignant tumors.3 The age of the patient should always be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of adnexal masses, because the incidence of ovarian cancer increases from 15.7 to 54/100 000 at the age of 40 to 65.4

In childhood, nearly 65% of adnexal masses are functional cysts, 28% are benign ovarian tumors, and 8% are malignant ovarian neoplasms (dysgerminomas and immature teratomas). Dermoid cysts that originate from germ cells represent 65% of benign tumors in this age group.

In the reproductive age group, the majority of adnexal masses are benign, with malignancy found in only 7% to 13%.5 Functional cysts remain the most common type of adnexal mass found in this age group. In the differential diagnosis of the reproductive age patient, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, hydrosalpinx, and leiomyoma should always be kept in mind.

A large prospective study involving 15,106 asymptomatic patients age 50 or older reported that 18% of patients had unilocular cysts <10cm in diameter. Of all cysts, 69.4% resolved spontaneously, but 29.1% persisted or became complex. Pathologic tests identified serous cystadenoma (52%), serous cystadenofibroma (12%), mucinous cystadenoma (8%), paraovarian or paratubal cyst (8%), fibrothecoma (6%), endometrioma (4%), cystic teratoma (3%), mucinous cystadenofibroma (0.9%), or other benign lesions (7%).6 Patient age is crucial in diagnosing the probable cause of adnexal mass.

HISTORY

Obtaining a complete medical history of the patient and her family plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of adnexal masses. Risk factors for ovarian cancer include family history of epithelial ovarian cancer, breast cancer, BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, hereditary cancer syndromes, and a background of infertility. The incidence of ovarian cancer in patients with no family history of the disease is nearly 1.4%. A family history of ovarian cancer should alert the clinician in the management of adnexal masses of women especially between 35 and 45 years of age, because inherited forms of ovarian cancer represent 5% of all ovarian malignancies.7 In this age group, ultrasound screening should begin at a younger age. Women with a first-degree relative with ovarian cancer have a 5% risk of malignancy, but the 1994 National Institutes of Health consensus conference on ovarian cancer did not recommend routine screening of these patients.

Furthermore, there is a 30% lifetime risk for women with 2 affected relatives.8 In families with multiple cases of ovarian cancer, the risk approaches nearly 50% observed in dominantly inherited syndromes. The women with a family history of multiple ovarian cancer cases have a 3% to 10% risk of having 1 of the 3 forms of hereditary ovarian cancer syndrome below:

- site-specific syndrome

- breast-ovarian cancer syndrome

- Lynch syndrome II

Many studies have implicated 2 germline mutations, BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes, as a possible cause of hereditary ovarian cancer syndromes. Carriers of the BRCA1 mutation have an 80% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer and a 45% risk of ovarian cancer.

SYMPTOMS

The majority of adnexal masses are unfortunately asymptomatic unless they have been complicated with the rupture of cystic lesion or torsion of the mass. No specific symptoms indicate an ovarian mass that would lead women to seek medical care.

Dissemination of ovarian cancer in the peritoneal cavity may be asymptomatic at early stages of the disease, until ascites causes abdominal distention. Owing to the silent clinical expression of adnexal masses, especially malignancies, such cases have been defined as “silent killers,” but recent studies refute this situation. Olson et al9 reported that of 168 cases of ovarian cancer, 93% of women had at least one symptom, compared with 42% of controls. The most common symptoms among these patients compared with the control subjects included unusual abdominal bloating or pressure in the abdomen or pelvis (71% vs. 9%, respectively), abdominal or back pain (52% vs.15%, respectively), and generalized lack of energy (43% vs. 16%, respectively). The patients with cancer had a more recent onset of symptoms compared with controls. In another study, Goff et al10 prospectively evaluated 128 patients presenting with either a benign or malignant adnexal mass. Patients in the ovarian cancer group had a higher rate of symptoms for pelvic, abdominal, back pain, bloating, and increased abdominal size. Women with malignant masses had more symptomatic episodes, more severe symptoms, and more recent onset of symptoms. Consequently, when obtaining a history from a patient with an adnexal mass, the physician should carefully discuss any current symptoms.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A complete physical examination is necessary for every patient with signs and symptoms of an adnexal mass, because palpation of an asymptomatic adnexal mass during routine pelvic examination is still the most common method for the detection of neoplasms. The Clinicians Handbook of Preventive Services11 recognizes the bimanual examination as part of the routine gynecologic examination but does not recommend it as an ovarian cancer-screening tool. Bimanual and rectovaginal examinations are the basic and the common components of an initial physical examination. Bimanual examination helps to determine the size, location, mobility, and consistency of the mass; the rectovaginal examination allows for assessment of the Douglas pouch, rectum, posterior surface of the uterus, and the parametria. Benign tumors are generally unilateral, cystic, and mobile. On the other hand, malignant adnexal masses are usually fixed, solid-irregular shaped, accompanied by ascites, and rapidly increase in size.12

LABORATORY FINDINGS

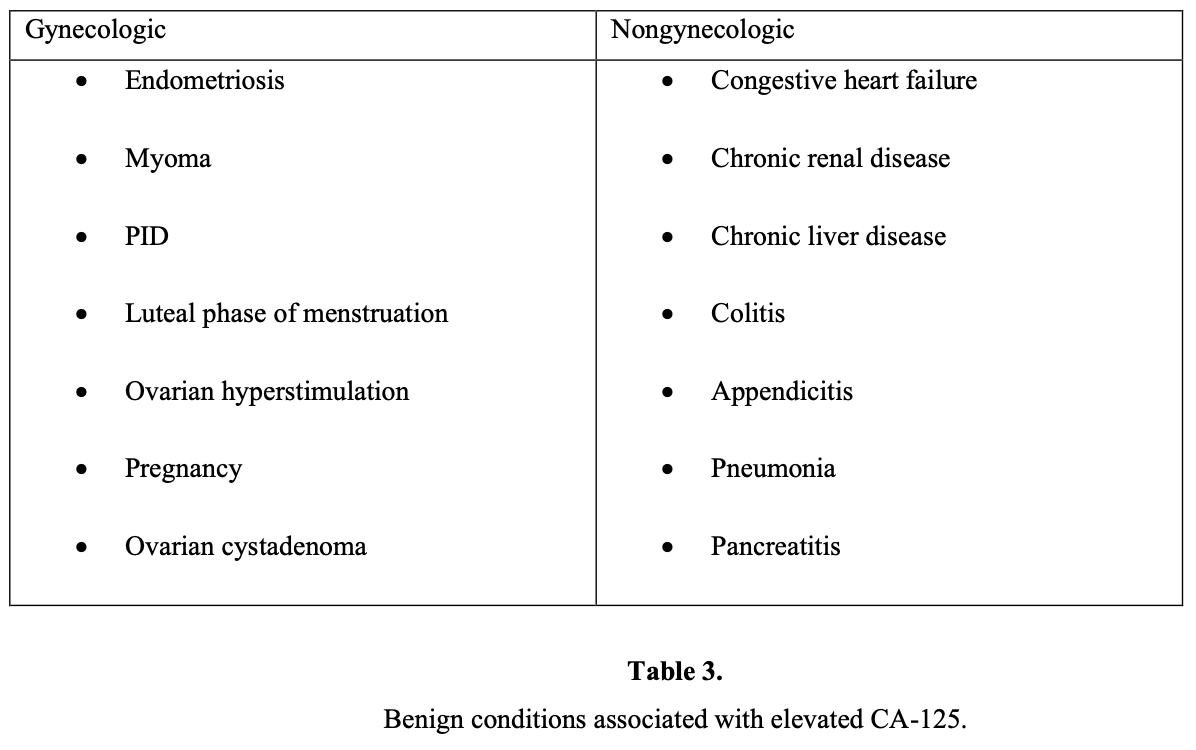

No single marker has been shown to be sufficiently sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer currently. CA-125 has been studied extensively as a screening tool. It has been shown to be elevated in 90% of patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer,13 50% of patients with stage I ovarian cancer, and 1% of the normal population. An additional problem with serum CA-125 as a screening test is that several benign conditions may cause an increase in serum levels (false-positivity) as shown in below:

An elevated CA-125 is also found in several other carcinomas, for example pancreas, colon, lung, and breast. The sensitivity and false-positive rate of the CA-125 range between 50% and 83% and 14% and 36%, respectively.14 CA-125 is more useful in the postmenopausal population. Another study found that a preoperative CA-125 examination of >65 IU/mL accurately predicted ovarian cancer in 49% of premenopausal women and in 98% of postmenopausal women.15 Another study revealed that levels >65 IU/mL in postmenopausal women with an ultrasonographically suspicious pelvic mass have been shown to have a positive predictive value of 97%.16 Changes in the level of CA-125 can be used as a reliable indicator of response or progression, but it does not yet have a clear place in diagnosis or prognosis.17

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

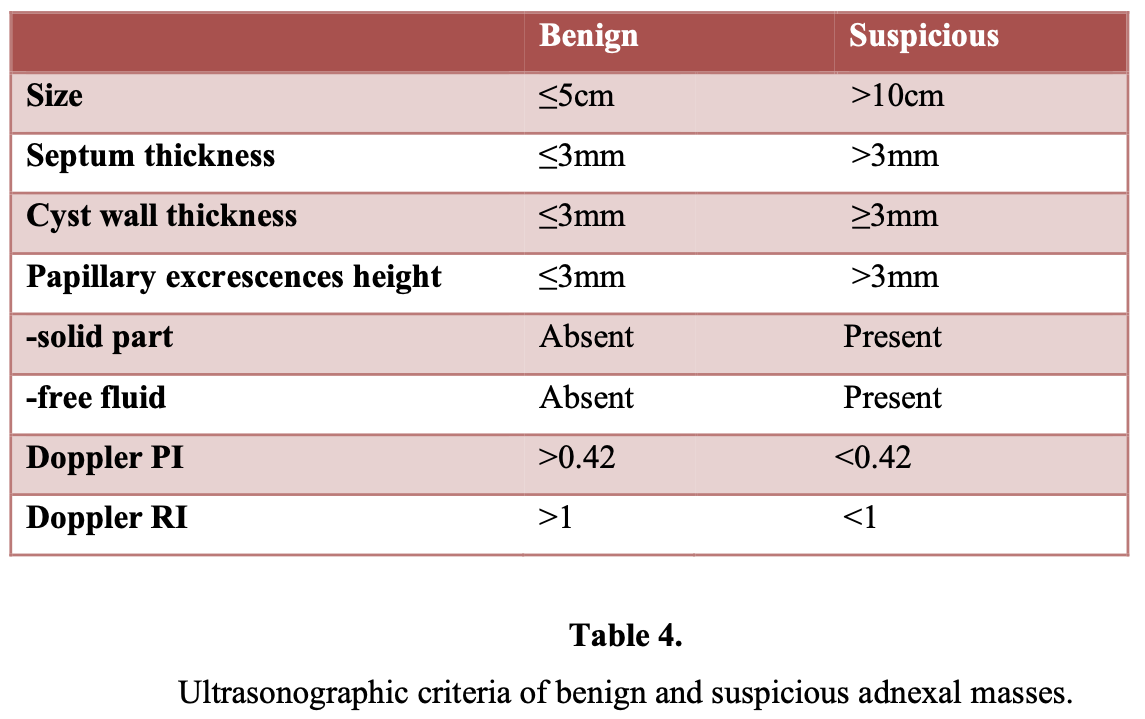

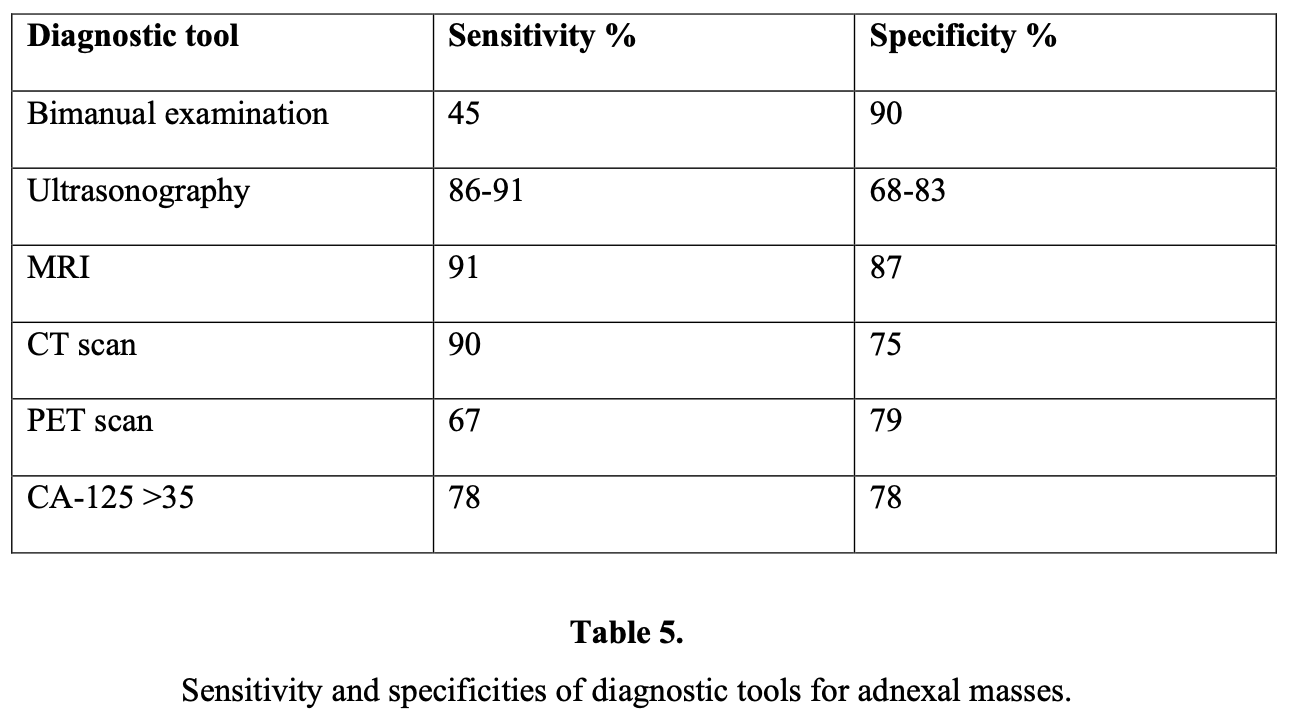

Pelvic ultrasound is currently considered as the most useful technique for diagnostic evaluation of the adnexal mass. In particular, transvaginal ultrasound provides better resolution than abdominal ultrasound does.18 The sensitivity and specificity of transvaginal ultrasound varies between 48% and 100% and 65% and 98%, respectively. On the other hand, sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasound varies between 60% and 93%, and the specificity varies between 42% and 95%. This discrepancy is related to the experience of the doctor and the criteria for malignancy that have been chosen.19

The parameters of ultrasonographic evaluation of adnexal mass are:

- Size

- Septum thickness

- Cyst wall thickness

- Number of loculi

- Presence of papillary or solid excrescences

- Overall echo density

- Pulsatility index (PI)

- Resistivity index (RI)

Sassone et al20 proposed a morphologic ultrasonographic scoring system to distinguish benign lesions from malignant ones. Transvaginal sonographic pelvic images of 143 patients were correlated with surgical and pathologic findings. The variables included in the scoring system were the wall thickness of the adnexal cyst, the inner wall structure, presence and thickness of septa, and echogenicity. Morphologic analysis with ultrasound has a reported sensitivity of 85% to 97% and a reported specificity of 56% to 95%. Other studies21,22 found that the risk of malignancy in simple cysts defined as unilocular with smooth inner wall increases from 0.8% in premenopausal women to 9.6% in postmenopausal women. In a prospective study, the positive predictive value of the sonographic evidence of malignancy was 73%, whereas benign tumors were predicted correctly in 95.6%.23

Most recently, Alcazar and Jurado24 developed a logistic model to predict malignancy based on menopausal status, ultrasound morphology, and color Doppler findings in 79 patients with adnexal masses. The authors derived a mathematical formula to estimate preoperative risk of malignancy. When this formula was applied prospectively, 56 of 58 (96.5%) adnexal masses were correctly classified.

There is no consensus about the sensitivity and specificity of Doppler ultrasound in the assessment of vascularity of adnexal masses, because it varies from 50% to 100%.25 It has been reported that 82.7% of benign adnexal masses may have peripherally and pericystically located vessels with resistance (RI) and pulsatility indexes (PI) of moderate to high (RI>0.42 and PI>1, respectively). On the contrary, malignant adnexal masses usually have centrally located vessels with low resistance and pulsatility indexes (RI<0.42 and PI<1, respectively).26

CT and MRI are not indicated routinely for evaluation of an adnexal mass. CT is probably better for localization of metastasis, but the major limitation of CT in detecting early ovarian cancer is its inability to detect lesions <2cm in diameter. Several studies have proved that MRI is superior to CT and Doppler ultrasound for diagnosing malignant ovarian masses, because it has a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 88%.27 In addition, the gadolinium-enhanced MRI increased the sensitivity to 100% and specificity to 98%, achieving an accuracy of 99%.28 However, the high cost of MR imaging is a disadvantage of applying this method.

Over the last decade, advances in laparoscopic techniques have led to increased use of laparoscopy in gynecologic surgery. As the technology improved, low complication rates for operative laparoscopy in such procedures as adnexectomy have been reported.29 Recently, scientific data have supported the concept, and the laparoscopic approach for treating adnexal masses is now considered the preferred treatment.

There is a growing body of evidence in the literature30-32 supporting the advantages of laparoscopy over laparotomy, because it is associated with the following:

- less de novo adhesion formation

- decreased febrile morbidity

- less postoperative pain

- less analgesic requirements

- shorter length of hospital stay

- faster recovery

- better cosmetic results

- reduced overall cost on the gynecologic health care of women

Despite the advantages of using laparoscopy to manage adnexal masses, there remains the fear of encountering cancer and performing inadequate staging or, worse yet, upstaging of the disease by tumor seeding. Careful patient selection for the appropriate use of laparoscopy in the management of adnexal masses is a critical issue.

DEFINITION OF SUSPICIOUS ADNEXAL MASS

Suspected ovarian neoplasms are a common problem in clinical practice. Although the majority of adnexal masses are benign, the physician’s primary goal should be excluding any malignant situations. The methods commonly used in the evaluation of a woman with a suspected adnexal mass are physical examination, ultrasound, and serum CA-125 levels, but no standard definition of suspected adnexal mass has been established.

Ultrasonographic evaluation of an adnexal mass can indicate that the lesion is either benign or suspicious.

The definition of a suspected adnexal mass was proposed by Childers et al33 in their prospective trial as:

- Abnormal appearance on ultrasonographic imaging, elevated CA-125 levels, or both of these;

- Absence of ascites or absence of malignant cells on paracentesis if ascites was present;

- Absence of upper abdominal masses on physical examination or on CT scan.

SURGICAL APPROACH FOR SUSPECTED ADNEXAL MASSES

Role of Laparoscopy

Although laparotomy is touted to be the standard, the advances in modern laparoscopy have made physicians reconsider the appropriate surgical approach to adnexal masses. Published opinion regarding the role of laparoscopic surgery in the management of a mass at moderate/high risk of malignancy is divided between those supporting its use3,34-38 and those advising laparotomy when malignancy is suspected.39-44 Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses has been controversial since its inception, and new questions have arisen in recent years about the limits of laparoscopy as follows:

- The role of laparoscopy in gynecologic oncology?

- The rate of malignancy?

- The risk of tumor spillage?

- The risk of inadequate resection and surgical staging?

- The incidence of port-site metastasis?

- The risk of leading to reexploration?

- The risk of delay in chemotherapy?

- Amount of training required to perform operative laparoscopy safely and efficiently?

On the other hand, the benefits of the laparoscopic approach to all adnexal masses results in avoiding unnecessary laparotomy overtreatment. Reduced hospital stay, low morbidity, decreased postoperative pain and recovery time,45 less adhesion formation,46 and lower cost to the patient and the hospital47 are other advantages of this laparoscopy.

Most adnexal masses are benign, with malignancy found in only 7% to 13% of premenopausal and 8% to 45% of postmenopausal patients.48 Combining ultrasonographic techniques with serum tumor markers has established criteria to differentiate benign and malignant masses, which helps physicians to decide on the surgical procedure. However, none of the above-available modalities can offer 100% specificity and sensitivity in differentiating malignant from benign adnexal masses, but they do help to minimize the incidence of unsuspected malignancy at laparoscopy.

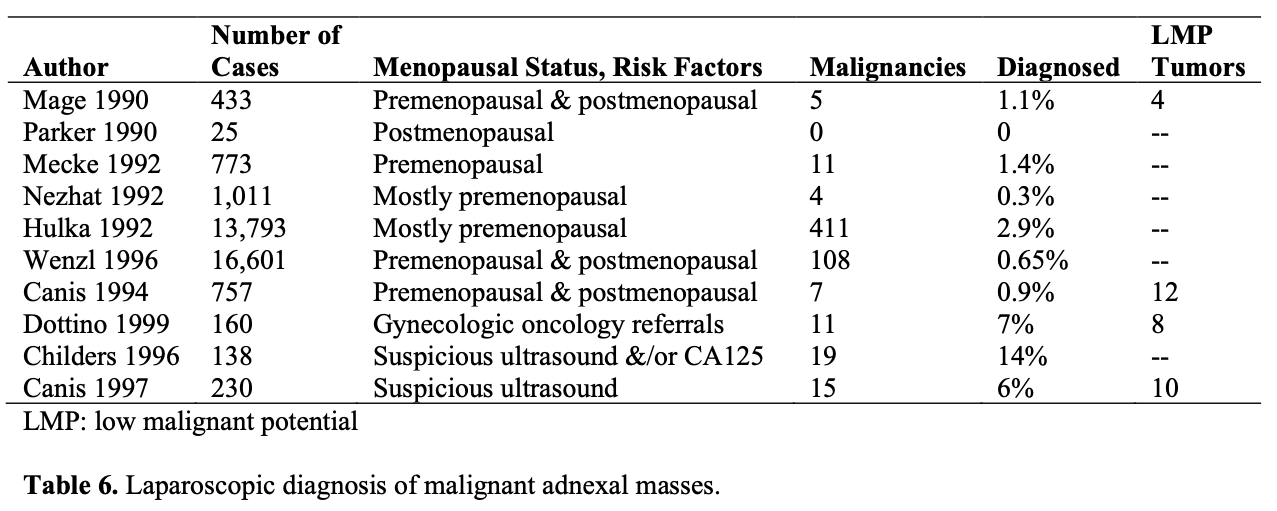

Laparoscopy as a Diagnostic Tool and Management of Suspicious Masses

The incidence of unsuspected malignancies at laparoscopy is only 0.04% according to the 1990 survey of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.49 The rate at which these malignancies are discovered intraoperatively depends on risk factors, such as patient age, size and complexity of the mass, and the patient’s preoperative serum CA- 125 level. Maiman et al42 reported that laparoscopic visualization might fail to identify cancer in one-third of the cases. However, to become a standard for the management of gynecologic malignancies, the procedure should be proven to be a safe alternative for the current management and must not compromise accurate surgical staging or diagnosis of malignancy.

The main goal of surgery in the management of adnexal masses should be complete and immediate treatment of the mass. Benign tumors should be treated using ovarian- preserving procedures, and malignant tumors should be staged as soon as possible.

During the examination of a mass, the procedure should include careful inspection of:

- all peritoneal surfaces

- pelvis

- pouch of Douglas

- diaphragm

- paracolic gutters

- omentum

- bowel surfaces

It is recommended that peritoneal washings be obtained and that great care should be taken to remove the cyst without rupture or spillage of cyst contents into the peritoneal cavity. Procurement of intraperitoneal washings for cytologic testing should be accomplished before the initiation of any operative procedure. Avoidance of capsular rupture should be attempted.

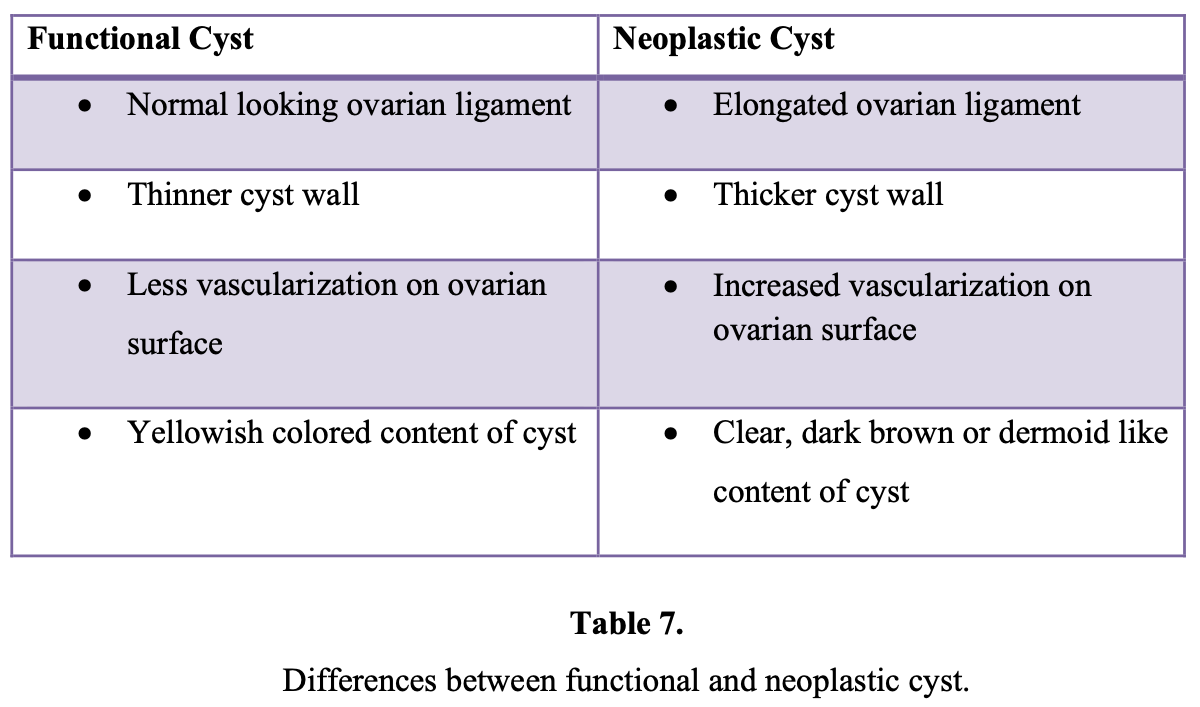

Several methods are currently used by clinicians to manage adnexal masses. These are aspiration, cystoscopy, biopsy directly from the lesion, cystectomy, oophorectomy, and adnexectomy. A metaanalysis50 showed that aspiration cytology of ovarian cysts had a negative predictive value of 58% to 98% in the diagnosis of malignancy. Also, cyst aspiration may result in the slow leak of malignant cells and increase the chance of malignant tumor cell implantation on peritoneal surfaces.51 Aspiration of ovarian cysts is ineffective in achieving resolution, because 11% to 67% of cysts will recur.50 Therefore, laparoscopic aspiration of ovarian cysts should not be performed as an aid to diagnosis and treatment of suspected malignant lesions.

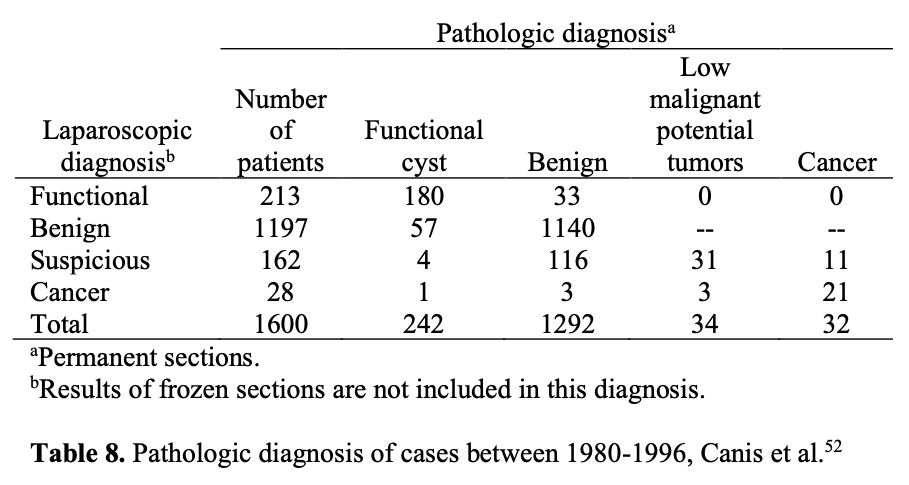

Given that there is no way to preoperatively identify malignant adnexal masses with 100% sensitivity and specificity, laparoscopy has been used to aid in the triage of these patients and improve the accuracy of assessment. In a study including 1600 adnexal mass cases managed laparoscopically for 16 years of follow-up revealed that sensitivity of laparoscopy was 100%, the positive predictive value was 34.7%, and the negative predictive value was 100%.52 The author reported that laparoscopic treatment appears to be safe, effective, nontraumatic, and preserves ovarian tissue and fertility.

The same investigators prospectively managed 247 suspicious masses laparoscopically, as long as there was no evidence of disseminated cancer in the pelvis or abdomen. They found that 85% of the suspicious adnexal masses proved benign, sparing laparotomy in nearly 94% of patients with a benign mass. The remaining 37 suspicious adnexal masses were malignant, and 19% of them were surgically managed by laparoscopy alone.

Overall, the authors treated nearly 83% of the women with suspicious adnexal masses by laparoscopic approach and avoided 41 laparotomies. Others have verified their data.34,53

In another study,33 138 patients with suspicious adnexal masses underwent laparoscopic surgery. Masses >10cm required laparoscopic drainage. Masses <10cm were removed with endoscopic sacs either through the anterior abdominal wall or through colpotomy incisions. A benign pathologic condition was found in 86% (119/138) of the patients.

Nineteen malignancies were diagnosed; 16 were adnexal primaries and 3 were nongynecologic. Ninety-five percent (113/119) of the benign masses and 74% (14/19) of the malignant masses were managed laparoscopically. Investigators in this study reported significant advantages with laparoscopic management, such as a short hospital stay and less overtreatment.33 To reduce the unnecessary laparotomies for suspicious adnexal masses according to preoperative evaluation, Canis et al54 suggested the following algorithm:

- Preoperative evaluation of adnexal masses is accomplished by using ultrasonography, Doppler, and tumor markers, while MRI should be applied only in the case of suspicious masses, because it provides additional information about the specific characteristics of the tumor.

- Then the adnexal masses that are considered benign can be managed effectively laparoscopically.

- The remaining suspicious masses can be managed laparoscopically, only by experienced laparoscopic surgeons, thus resulting in a 40% reduction in laparotomies for benign adnexal masses according to permanent histological results. After careful inspection of the upper abdomen, ovaries, and peritoneum, peritoneal washings are obtained for immediate cytologic examination.

- In low suspicious masses, especially in young women <40 years old, puncture followed by endocystic examination is performed with the use of a strong aspiration system and peritoneal lavage to minimize spillage. Then any suspicious mass should be sent for frozen section analysis. With this approach, the ultrasonographicallysuspicious masses declined from 6% to 12.1% at diagnostic laparoscopy.

- In highly suspicious masses, laparoscopic adnexectomy without puncture is performed. Adnexal mass is extracted in an endoscopic bag to prevent spillage into the peritoneal cavity.

In the case of malignancy, an immediate staging procedure should be performed whenever possible if the frozen section confirms the laparoscopic diagnosis.

IF A MALIGNANCY IS DIAGNOSED DURING OR AFTER A LAPAROSCOPIC PROCEDURE

Two management options are available at the diagnosis of apparent stage I ovarian cancer at laparoscopy usually after frozen-section analysis:

- immediate surgical staging

- reschedule definitive surgical staging later

The decision will depend on the availability of a trained surgeon and the patient’s preoperative counseling and expectations. Formal surgical staging is undoubtedly necessary because 28% of cases of apparent stage I ovarian cancer will be upgraded when a definitive staging procedure is performed.57 Therefore, patients with an ovarian malignancy will have improved survival if the malignancy is appropriately staged during the initial surgical procedure by a gynecologic oncologist.

A delay in appropriate staging is one of the controversial subjects affecting survival rates. There have been no published studies regarding the effect of surgical delay on survival in ovarian cancer. Most of the available data involve surgical delay before laparotomy and are conflicting. One study shows a correlation between surgical delay and increasing stage56 and others do not.57-59 The unknown negative effect of laparoscopic procedures, which may include inspection only, cystectomy, or adnexectomy before delayed definitive staging, is another controversy. A retrospective analysis of the effect of delayed staging laparotomy after laparoscopic removal of ovarian masses later found to be malignant reported that in 24 of 48 cases staging laparotomy was performed within 17 days of laparoscopy, and in the other 24 cases, there was a delay of more than 17 days.60 On univariate analysis, there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of advanced stage tumors (both malignant and LMP) among patients in whom laparotomy was delayed for more than 17 days. However, on multivariate analysis, this difference was statistically significant only for LMP tumors.

In another retrospective survey40 of 192 ovarian malignancies managed laparoscopically, it was reported that when the delay between laparoscopic biopsy and definitive surgery was more than 8 days, port-site metastases developed in 56% (5/9) of cases of apparent stage IC–II (but unstaged) ovarian cancer and in 47% (8/17) of cases of stage III ovarian cancer.

Of 72 cases of apparent stage 1A (unstaged) ovarian cancer, there was rapid progression to stage III disease at laparotomy in 39% (28/72). Unfortunately, it is not possible to isolate surgical delay as the main factor causing disease progression, but spill from the ovarian capsule and delay until definitive surgery can be associated with the rapid progression of tumor stage.

The optimal timing of surgery for staging after a laparoscopic procedure has not been clearly established; however, Canis et al61 have suggested that this be considered an “oncologic emergency” and should be performed as soon as possible. According to the same authors, delayed staging after unilateral adnexectomy seems acceptable,52 whereas biopsy or partial resection followed by a delayed adnexectomy and restaging are probably associated with a higher risk of postoperative dissemination.

Maiman et al42 surveyed members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists and reported 42 referred cases of laparoscopic management of ovarian carcinoma, delayed laparotomy as a second procedure was noted in 71% of patients, with an average delay of 4.8 weeks between procedures. Crawford et al62 surveyed members of the British Gynaecologic Cancer Society, and 21 cases of ovarian cancer in which laparoscopy had been performed were identified. None of these patients underwent immediate laparotomy for staging, and the mean delay between diagnosis and staging was 6.5 weeks.

The mean time interval between the initial laparoscopic procedure and surgical staging has been reported as 2.5 weeks in a study in Finland41 and 12.5 weeks in a study in Austria.39

Management of Masses in Reproductive Age Patients

In reproductive age patients, functional cysts are the most common adnexal masses, usually ultrasonographically benign looking, are <10cm in diameter, and patients have normal CA-125 levels. Usually in 50% to 90% of patients, they resolve spontaneously in 4 weeks to 6 weeks with or without oral contraceptives.63 Persistence, torsion, recurrence after aspiration, or persistence of symptoms requires laparoscopic evaluation.

Indications for surgery

- Masses >8cm diameter

- Failure to resolve within 2 months to 6 months

- Persistent pain

- Family history

- Lesions found incidentally while surgery for other indications is being performed

The principles of cancer surgery should apply to the treatment of benign-appearing or suspected lesions, because masses thought to be benign will be diagnosed as malignant with the rate of 0%, 4%, 2%, and 9%, and masses thought to be suspicious will be diagnosed as malignant with the rate of 6%, 5%, to 14%.3,33,52,55 Canis52 reported the results of a 12-year study of laparoscopically managed benign ovarian cysts that demonstrated a low complication rate of 1.5%, effectiveness of the procedure with a recurrence rate of 1.8%, and preservation of fertility after laparoscopic management.

Over the last decade, the management of non cystic masses has been one of the biggest controversies about the management of adnexal mass. According to the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, the majority of clinicians consider laparotomy the safest treatment for non cystic masses.49 On the other hand, Dottino et al34 reported laparoscopy to be safe in 88% of 160 pre- and postmenopausal patients with suspicious adnexal masses of which 9% were found to be malignant and 5% were LMP. They reported a 3% rate of intraoperative complications.34 Chapron et al19 reported that 11% of 228 masses evaluated preoperatively as “high risk” were found not to have features of malignancy during laparoscopy; all 26 patients were spared unnecessary surgery because a frozen section diagnosis of the excised adnexa was obtained.19 All authors pointed out the importance of preoperative evaluation of the mass, availability of immediate frozen section analysis, the ability to convert to laparotomy, and surgical expertise.

Management of Masses in Postmenopausal Age

An adnexal mass in a postmenopausal woman needs to be evaluated carefully, and the physician has to exclude malignancy, especially in this age group owing to the high incidence rate (up to 45%64). The standard operative approach to adnexal masses in postmenopausal women has been exploratory laparotomy to achieve adequate exposure for the treatment of ovarian cancer. But in the last 2 decades, many authors have questioned the use of standard laparotomic management. In some series, up to 75% of tumors were found to be histologically benign, as Dottino et al34 reported in their prospective study. Cystectomy in postmenopausal woman is not recommended; removal of the entire adnexa according to a frozen section diagnosis instead is warranted.

Removal of a normal-appearing contralateral ovary should be performed according to preoperative consultation and patient history.

The decision to perform laparotomy may be made in the following instances:

- If an adnexal mass is found to be highly suspicious due to ultrasonographic imaging with high serum levels of CA-125 before surgery;

- If the mass is macroscopically considered as suspicious during surgery;

- If malignancy is confirmed by frozen sections;

- If technical insufficiencies occurred during surgery.

Frozen Section Analysis

To provide optimal management of a patient with an adnexal mass, it is important to differentiate between malignant and benign pathology before and during surgery. In case of doubt about the state of malignancy before surgery, frozen section diagnosis might give additional information during surgery and help the surgeon decide which surgical procedure to use. This technique has been known since 1891, but studies on its diagnostic accuracy have only been performed beginning 2 decades ago.6

Chapron et al19 designed a prospective study to find out the effectiveness of frozen- section analysis concerning 228 patients who underwent an adnexectomy for an ovarian mass. Twenty-six of the masses were considered suspicious according to preoperative evaluation and intraoperative-laparoscopic examination. All 26 patients underwent a laparoscopic adnexectomy with extraction of the excised tissues with an endoscopic bag, followed by frozen section. In all 26 cases, the results of frozen section concluded that the lesion was benign, and in every case the results of the frozen examination were confirmed by the final histological results. According to the study, it is possible that frozen-section analysis of macroscopically suspicious lesions during laparoscopy could help to avoid unnecessary laparotomies. But according to this study, the use of frozen sections must be carried out according to certain well-defined rules:

- The sample must be taken using an endoscopic bag to avoid any risk of parietal contamination;

- Reliability of the frozen section is correlated directly with the tissues examined; it is essential that the histopathologist has an adequate quantity of tissue.

Sampling during surgery is another controversial subject. Most false-negative diagnoses of malignancy in frozen sections are the consequence of inadequate tumor sampling, according to some authors.66,67 According to Canis et al68, frozen sections should not be used to determine the treatment of the ovary and/or of the adnexa. If the mass is macroscopically suspicious, the entire adnexa should be removed and sent to the pathologist. The only exception to this rule concerns adnexal masses with a small (<5mm) solitary vegetation, when the local conditions (diameter of the mass, pelvic adhesions, and others) allow satisfactory macroscopic inspection of the inner cyst wall. In this way, some younger patients (<40 years) may be treated by cystectomy, despite a small amount of intracystic vegetation. However, this approach should be used very cautiously, and if there is any doubt, or if dissection is difficult, an adnexectomy should be performed.

On the other hand, in a prospective study of 160 patients with adnexal masses treated at a gynecologic oncology service, Dottino et al34 found a discrepancy between the frozen section and final pathologic assessment in 3% of the cases. However, Nezhat et al3 reported that the most reliable indicators of malignancy in their study concerning laparoscopic management of 1011 adnexal mass cases were the combination of laparoscopic visualization of the whole peritoneal cavity and frozen-section analysis. It seems, therefore, that 2 controversial situations exist regarding the accuracy of frozen- section analysis: (1) cases with very large tumors and (2) tumors with borderline characteristics. In both cases, accuracy depends on the relative risk of the sampling.

Risks of Laparoscopy

Improvements in the laparoscopic surgery technique make this approach more universal day by day, but many authors have recently reported the risks of this procedure. These risks include the following:

- Failure to diagnose malignancy and subsequent delay in adequate treatment;

- Cyst rupture and spillage;

- Port-site metastases;

- Intraperitoneal tumor dissemination.

Cyst Rupture and Spillage

The rate of cyst rupture with laparoscopy is 6% to 27%, according to several studies.69-71 However, few studies differentiate between cyst rupture with cystectomy and with adnexectomy. According to some authors, the rate of rupture and spillage with laparoscopic adnexectomy is minimal and equivalent to that for laparotomy.69,72

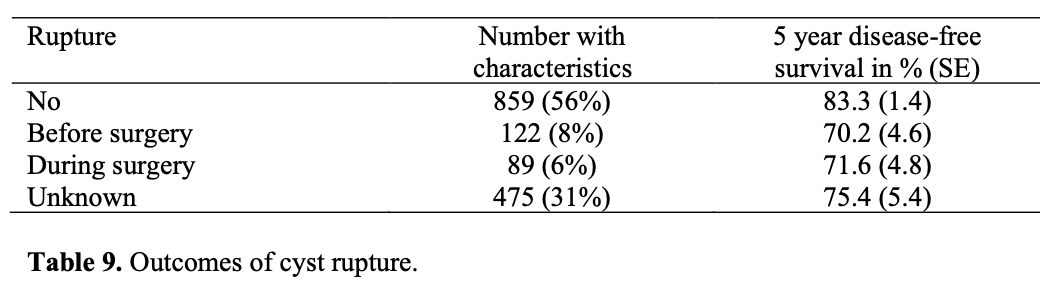

Laparoscopic cystectomy may ultimately be proven to have a higher rate of spillage than laparotomy, although the data are not conclusive. There is a theoretical relation suggesting that in early ovarian cancer cases, intraoperative rupture of the capsule might lead to intraperitoneal dissemination of malignant cells, which makes the prognosis poorer. This view was proposed by Webb et al73 who showed that a ruptured cyst was associated with reduced 5-year survival in stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Also, Sjövall et al74 showed that there was a statistically significant decrease in survival in the group whose cysts ruptured before surgery compared with the group with intraoperative cyst rupture (78% vs 85%).

Tumor dissemination after laparoscopic management of early ovarian malignancies has always included spillage and delay according to the literature. From the other point of view, intraoperative rupture will upstage some malignant case from stage IA to IC and therefore necessitate the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients who may not otherwise have required it.75

Vergote et al76 designed a retrospective study in 2001 including 1545 patients from 6 countries who had epithelial ovarian cancer stage I. They revealed that ruptures before or during surgery were found to be independent and strong prognostic factors.

Controversially, several multivariate analyses did not confirm the risk related to puncture of malignant ovarian tumors.77-81 Sevelda et al77 found a 5-year survival of 76% in 30 patients with stage I ovarian cancer with capsular rupture and 76% in 30 similar patients who did not have capsular rupture. The multivariate analysis of 519 patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer by Dembo et al78 showed that tumor grade, ascites, and tumor adherence were significant predictors of 5-year disease-free survival but that tumor rupture was not predictive.

As a result, there is no consensus about the rupture of suspected adnexal masses, but it would be prudent to take every care during surgery to attempt to maintain capsular integrity to minimize any possible risk of tumor dissemination and when deciding whether to puncture, the surgeon has to be alert because there are potential but unknown consequences for the prognosis.

Port-Site Metastases

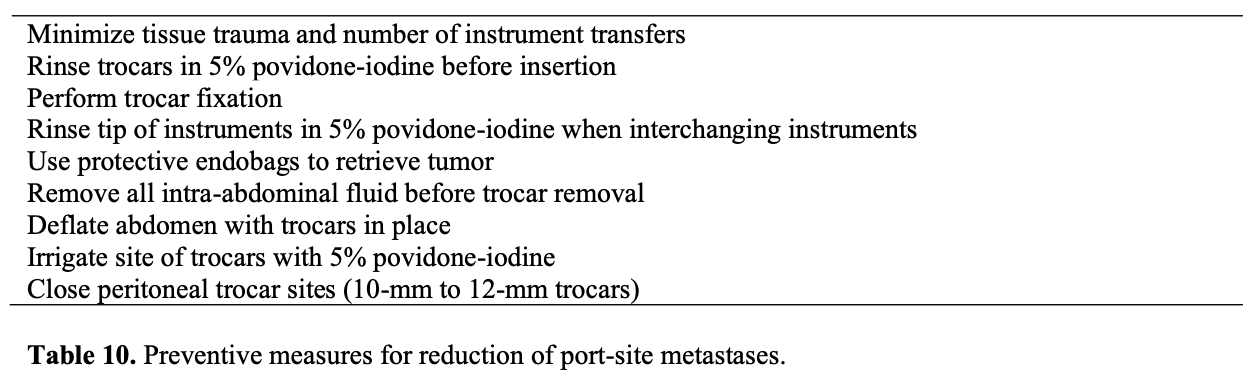

One concern with removing malignant lesions from the abdomen through laparoscopic port sites is the possibility of metastasis and recurrence at the sites. Some authors have noted that port-site metastasis may occur not only with higher-stage malignancies but also with tumors with low malignant potential. Port-site metastases, also called wound- site metastases, have been reported after both laparoscopy and laparotomy. The incidence of these complications has been 1% after laparotomy and 1% to 2% after laparoscopy, with a single study reporting an incidence of 16%.82,83 The most likely mechanism for port-site metastases seems to be direct contamination by the surgical procedure during tumor extraction, the postoperative withdrawal of contaminated ports and loss of abdominal insufflation, aerosolization of tumor cells, local immune reactions, which have been reported in colon and gallbladder surgery as well.84 Although port-site recurrences may be difficult to treat, no prospective evidence exists that metastases worsen the prognosis. In the only retrospective study addressing this issue, Kruitwagen et al82 failed to find a significant survival difference between patients with and without abdominal wall metastasis after adjusting for age, stage, grade, and the amount of residual disease after primary debulking. Ramirez et al85 proposed preventive measures for reduction of port- site metastases:

Intraperitoneal Tumor Dissemination

Several animal studies61 suggest increased tumor dissemination after a CO2 pneumoperitoneum. Voltz et al86 reported diffuse intraperitoneal tumor spread after laparoscopy in nude mice injected intraperitoneally with a human lung cancer cell line. The survival time was the shortest in the group of mice in which CO2 was used, compared with heated CO2 or helium. Canis et al87 used immune competent rats injected intraperitoneally with rat ovarian carcinoma cells and divided them into 4 groups. In the high-pressure pneumoperitoneum group (10mm Hg), tumors were disseminated more diffusely than in the low-pressure pneumoperitoneum (4mm Hg) group. Canis et al52 also reported a case of pelvic dissemination found at a restaging procedure 3 weeks after initial adnexectomy for a well-differentiated serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary.

CONCLUSION

With growing interest in operative laparoscopy, management of the adnexal mass with this method offers the potential for safe, effective minimally invasive surgery. Indeed, laparoscopy is considered safe and effective in the initial surgical evaluation of adnexal masses if strict guidelines are used, frozen-section analysis is available, and principles of cancer surgery are respected. It is now accepted practice in the routine management of benign adnexal masses; however, laparotomy remains the gold standard for the management of ovarian cancer.

References

- Pejovic T, Nezhat F. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses: the opportunities and the risks. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;943:255-268.

- Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Accuracy of the pelvic examination in detecting adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:593-598.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Welander CE, Benigno B. Four ovarian cancers diagnosed during laparoscopic management of 1011 women with adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:790-796.

- Donnez J, Nisolle M, Gillet N, Smets M, Bassil S, Casanas-Roux F. Large ovarian endometriomas. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(3):641-646.

- Disaia PJ, Creasman WT. The adnexal mass and early ovarian cancer. In: Clinical Gynecologic Oncology. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;1997:253-281.

- Modesitt SC, Pavlik EJ, Ueland FR, DePriest PD, Kryscio RJ, van Nagell JR Jr. Risk of malignancy in unilocular ovarian cystic tumors less than 10 centimeters in diameter. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:594-599.

- Lynch HT, Albano WA, Lynch JF, Lynch PM, Campbell A. Surveillance and management of patients at high genetic risk for ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:589-596.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Statement. Ovarian cancer: screening, treatment, and follow-up. JAMA. 1995;273:491-497.

- Olson SH, Mignone L, Nakraseive C, Caputo TA, Barakat RR, Harlap S. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:212-217.

- Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004;291:2705-2712.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, Office of Public Health and Science, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Clinician’s Handbook of Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 1998.

- Paula JAH. Benign diseases of the female reproductive tract: symptoms and signs. In: Novak’s Gynecology. 13th ed. Jonathan SB, ed. Philadelphia: E. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:351-420.

- Jacobs I, Bast RC Jr. The CA 125 tumour-associated antigen: a review of the literature. Hum Reprod. 1989;4:1-12.

- Knudsen UL. Management of ovarian cysts. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:1012-1021.

- Malkasian GD Jr, Knapp RC, Lavin PT, et al. Preoperative evaluation of serum CA 125 levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients with pelvic masses: discrimination of benign from malignant disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:341- 346.

- Brooks SE. Preoperative evaluation of patients with suspicious ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55:80-90.

- Meyer T, Rustin GSJ. Role of tumor markers in monitoring epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1535-1538.

- Kurjak A, Predanic M, Kupesic S. Transvaginal color and pulsed Doppler assessment of adnexal tumor vascularity. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:3-8.

- Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Fritel X, Rambaud D. Diagnosis and management of organic ovarian cysts: indications and procedures for laparoscopy. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2(5):435-446.

- Sassone AM,Tımor Tritsch IE, Artner A.et.al.Transvaginal sonographic characterization of ovarian disease:evaluation of a new scoring system to predict ovarian malignancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:70-76.

- Osmers RG, Osners Nm von Maydell B, Wagner B, Kuhn W. Preoperative evaluation of ovarian tumors in the premenopause by transvaginosonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:428-434.

- Osmers RG, Osmers M, Von Maydell B, Wagner B, Kuhn W. Evaluation of ovarian tumors in postmenopausal women by transvaginal sonography. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;77:81-88.

- Herrmann UJ, Locher GW, Goldrisch A. Sonographic patterns of ovarian tumors: prediction of malignancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:777-781.

- Alcazar JL, Jurado M. Prospective evaluation of a logistic model based on sonographic morphologic and color Doppler findings developed to predict adnexal malignancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18:837-842.

- Exacoustos C, Romanini ME, Rinaldo D, et al. Preoperative sonographic features of borderline ovarian tumors. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:50-59.

- Kurjak A Predanic M, Fleischer A, Kupesic S. Malignant adnexal masses. In: Doppler Ultrasound in Gynecology. Kurjak A, Fleischer AC, eds. Lancashire, UK: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 1998:47-60.

- Kurtz AB, Tsimikas JV, Tempany CM, et al. Diagnosis and staging of ovarian cancer: comparative values of Doppler and conventional US, CT, and MR imaging correlated with surgery and histopathologic analysis–report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1999;212:19-27.

- Komatsu T, Konishi I, Mandai M, et al. Adnexal masses: transvaginal US and gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging assessment of intratumoral structure. Radiology. 1996;198:109-115.

- Semm K, Mettler Technical progress in pelvic surgery via operative laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:121-127.

- Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Bozzetti MC, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;20(3):CD004751.

- Pados G, Devroey P. Adhesions. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;4:412-418.

- Deckardt R, Saks M, Graeff H. Comparison of minimally invasive surgery and laparotomy in the treatment of adnexal masses. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc.1994;1:338-339.

- Childers J, Nasseri A, Surwıt EA. Laparoscopic management of suspicious adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1171-1179.

- Dottino P, Levine D, Ripley D. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:223-228.

- Pomel C, Provencher D, Dauplat J, et al. Laparoscopic staging of early ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;58:301-306.

- Childers J, Lang J, Surwit E, Hatch KD. Laparoscopic surgical staging of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:25-33.

- Magrina JF. Laparoscopic surgery for gynecologic cancers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:619-640.

- Kadar N. Laparoscopic management of gynecologic malignancies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:247-255.

- Wenzl R, Lehner R, Husslein P, Sevelda P. Laparoscopic surgery in cases of ovarian malignancies: an Austria-wide survey. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;63:57-61.

- Kindermann G, Massen V, Kuhn W. Laparoscopic management of ovarian tumors subsequently diagnosed as malignant. J Pelvic Surg. 1996;2:245-251.

- Leminen A, Lehtovirta P. Spread of ovarian cancer after laparoscopic surgery: report of eight cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:387-390.

- Maiman M, Seltzer V, Boyce J. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian neoplasms subsequently found to be malignant. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:563-565.

- Chi D, Curtin J. Gynecologic cancer and laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1999;26:201-215.

- Parker WH. Management of adnexal masses by operative laparoscopy. Selection criteria. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:603-606.

- Davidson JW. Comparative study of operative laparoscopy vs. laparotomy: analysis of the financial impact. Reprod Med. 1993;38:357-360.

- Lundorff P, Thorburn J, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, Thorburn J, Lindblom B. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomized trial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:911-915.

- Maruiri F, Azziz A. Laparoscopic surgery for ectopic pregnancies: technology assessment and public health implications. Technol Steril. 1993;59:487-498.

- Parker WH, Berek JS. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 1994;21:79-92.

- Hulka JT, Parker WH, Surrey MW. American Association of Gynecologists and Laparoscopists. Survey of management of ovarian masses in 1990. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:599-602.

- Nicklin J, Eijkeren M, Athanasatos P. A comparison of ovarian cyst aspirate cytology and histology. The case against aspiration of cystic pelvic masses. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;34:546-549.

- Trimbos J, Hacker N. The case against aspirating ovarian cysts. Cancer. 1993;72: 828-831.

- Canis M, Pouly JL, Wattiez A, Mage G, Manhes H, Bruhat MA. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses suspicious at ultrasound. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89: 679- 683.

- Biran G, Golan A, Sagiv R, Glezerman M, Menczer J. Conversion of laparoscopy to laparotomy due to adnexal malignancy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;23:157-160.

- Canis M, Rabischong B, Houlle C, et al. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses: a gold standard? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:423-428.

- Herrmann UJ, Locher G, Goldhirsch A. Sonographic patterns of ovarian tumors: prediction of malignancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:777-781.

- Wikborn C, Pettersson F, Moberg P. Delay in diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;52:263-267.

- Fruchter R, Boyce J. Delays in diagnosis and stage of disease in gynecologic cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 1981;4:481-486.

- Smith E, Anderson B. The effects of symptoms and delay in seeking diagnosis on stage of disease at diagnosis among women with cancers of the ovary. Cancer. 1985;56:2727-2732.

- Flam F, Einhorn N, Sjovall K. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1988;27:53-57.

- Lehner R,Wenzl R,Heinzl et. al.Influence of delayed staging laparotomy after laparoscopic removal of ovarian masses later found malignant. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:967-971

- Canis M, Botchorishvili R, Wattiez A, et al. Cancer and laparoscopy, experimental studies: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91:1-9.

- Crawford R, Gore M, Shepherd J. Ovarian cancers related to minimal access surgery. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:726-730.

- Drake J. Diagnosis and management of the adnexal mass. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:2471-2476, 2479-2480.

- Mahdavi A, Berker B, Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2002;31:581-592.

- Slavutin LS, Rotterdam HZ. Frozen section diagnosis of serous epithelial tumours of the ovary. Am J Diagnostic Gynecol Obstet. 1979;1:89-94.

- Twaalfhoven FC, Peters AA, Trimos JB, Hermans J, Fleuren GJ. The accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;41:189-192.

- Obiakor I, Maiman M, Mittal K, Awobuluyi M, DiMaio T, Demopoulos R. The accuracy of frozen sections in the diagnosis of ovarian neoplasms. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;43:61-63.

- Canis M, Botchorishvill R, Manhes H, et al. Management of Adnexal Masses, the role and risks of laparoscopy. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:28-35.

- Yuen PM, Yu KM, Yip SK, Lau WC, Rogers MS, Chang A. A randomized prospective study of laparoscopy and laparotomy in the management of benign ovarian masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:109-114.

- Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Ercoli A, et al. A prospective randomized study of laparoscopy and minilaparotomy in the management of benign adnexal masses. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2367-2371.

- Havrilesky LJ, Peterson BL, Dryden DK, Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Berchuck A. Predictors of clinical outcomes in the laparoscopic management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:243-251.

- Gal D, Lind L, Lovecchio JL, Kohn N. Comparative study of laparoscopy vs. laparotomy for adnexal surgery: efficacy, safety, and cyst rupture. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:153-158.

- Webb M, Decker D, Mussey E. Factor influencing survival in Stage I ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;116:222-228.

- Sjövall K, Nilsson B, Einhorn N. Different types of rupture of the tumor capsule and the impact on survival in early ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1994;4: 333- 336.

- Berek J. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Berek J, Hacker N, eds. Practical Gynecologic Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:457-522.

- Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in invasive stage 1 epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176-182.

- Sevelda P, Vavra N, Schemper M, Salzer H. Prognostic factors for survival in stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 1990;65:2349-2352.

- Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, Berle EJ, Bush RS, Kjorstad K. Prognostic factors in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:263-273.

- Finn CB, Luesley DM, Buxton EJ, et al. Is stage I epithelial ovarian cancer overtreated both surgically and systemically? Results of a five-year cancer registry review. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:54-58.

- Vergote IB, Kaern J, Abeler VM, Pettersen EO, De Vos LN, Tropé CG. Analysis of prognostic factors in stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma: importance of degree of differentiation and deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy in predicting relapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;160:40-52.

- Sjövall K, Nilsson B, Einhorn N. Prognostic incidence of intraoperative rupture of malignant ovarian tumor with immediate surgical treatment. In: Bruhat MA, ed. Proceedings of the 1st European Congress on Gynecologic Endoscopy. London: Blackwell; 1994:107-108

- Childers J, Aqua KA, Surwit EA, Hallum AV, Hatch KD. Abdominal wall tumor implantation after laparoscopy for malignant conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:765- 769.

- Kruitwagen R, Swinkels BM, Keyser KG, Doesburg WH, Schijf CP. Incidence and effect on survival of abdominal wall metastases at trocar puncture sites following laparoscopy or paracentesis in women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:233- 237.

- Paolucci V, Schaelf B, Schneider M, Gutt J. Tumor seeding following laparoscopy: international survey. World J Surg. 1999;23:989-997.

- Ramirez PT, Wolf JK, Levenback C. Laparoscopic port-site metastases: etiology and prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:179-189.

- Voltz J, Paolucci V, Schaeff B. Laparoscopic surgery: the effects of insufflation gas on tumour-induced lethality in nude mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:793-795.

- Canis M, Botchorishvili R, Wattiez A, Mag G, Pouly JL, Bruhat MA. Tumor growth and dissemination after laparotomy and CO2 pneumoperitoneum: a rat ovarian cancer model. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:104-108.

- Manolitsas T, Fowler J. Role of laparoscopy in the management of adnexal mass and staging of gynecologic cancers. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;44(3):495-521.

- Hilger WS, Magrina JF, Magtibay PM. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49 (3):535-548.

- Pados G. Laparoscopic management of the adnexal mass. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006; 1092:211-228.