Subtotal Hysterectomy:

Classic Intrafascial Supracervical Hysterectomy (CISH Technique) and Laparoscopic Supracervical Hysterectomy (LASH)

Liselotte Mettler, Prof. Dr. med., Thoralf Schollmeyer, Dr. med., John Morrison, MD, Ibrahim Alkatout, Dr. med.

INTRODUCTION

The first carefully and fully described abdominal supracervical hysterectomy was performed by Wilhelm Alexander Freund in 1878.1 This was the leading technique of hysterectomy for over 80 years until Tervilä2 described the danger of cervical cancer as 0.3% to 1.9% following supracervical hysterectomy. From 1950 onwards, hysterectomy was performed almost exclusively as total hysterectomy, until Kurt Semm revived interest in supracervical hysterectomy in the 1990s by introducing the Classic Intrafascial Supracervical Hysterectomy (CISH technique) to be performed by pelviscopy or laparotomy.3-9

ANATOMY

The blood supply to the uterus is by the uterine arteries with their ascending and descending branches supplying the tubes, bladder, and vagina. In the region of mesosalpinx, these blood vessels anastomose with branches of the ovarian artery in the utero-ovarian rete. The ovarian vessels pass through the infundibulopelvic ligament to the ovary. Rare cases of developmental malformations of the uterus, such as absence of the uterine cavity or malunion of the Mullarian ducts, eg, uterus subseptus, arcuate uterus, uterus bicornis, unicollis uterus, or uterus duplex, must be ruled out preoperatively.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Preservation of the cervix implies the existence of a healthy cervix. All cases with the slightest pathology on the cervix, be it a precancerous situation, endometriosis, or a frozen pelvis (postinfectious situation), exclude cervical preservation. The technique is also only applicable if the patient comes back for regular gynecological checkups, including PAP smears and palpation. Thus, it is not advisable to perform this surgery on patients who do not fulfil these criteria. Technically, both the CISH and the LASH (Laparoscopic Supracervical Hysterectomy) technique are applicable.

PRINCIPLES OF THE CISH TECHNIQUE using the Calibrated Uterine Resection Tool (CURT)

Today, the CISH technique, as one method of supracervical or subtotal hysterectomy, is unique and performed as follows (see attached educational video CISH):

To reduce or exclude the possible development of a cervical stump malignancy in the remaining cervical functional tissue, the transformation zone is resected. This can be accomplished by transvaginal cylindrical coring of the cervical tissue by using a 15-mm, 20-mm, or 24-mm CURT Set (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CURT Set: Guide Rod; Calibrated Stabilizing Tool; Morcellator.

Figure 1. CURT Set: Guide Rod; Calibrated Stabilizing Tool; Morcellator.

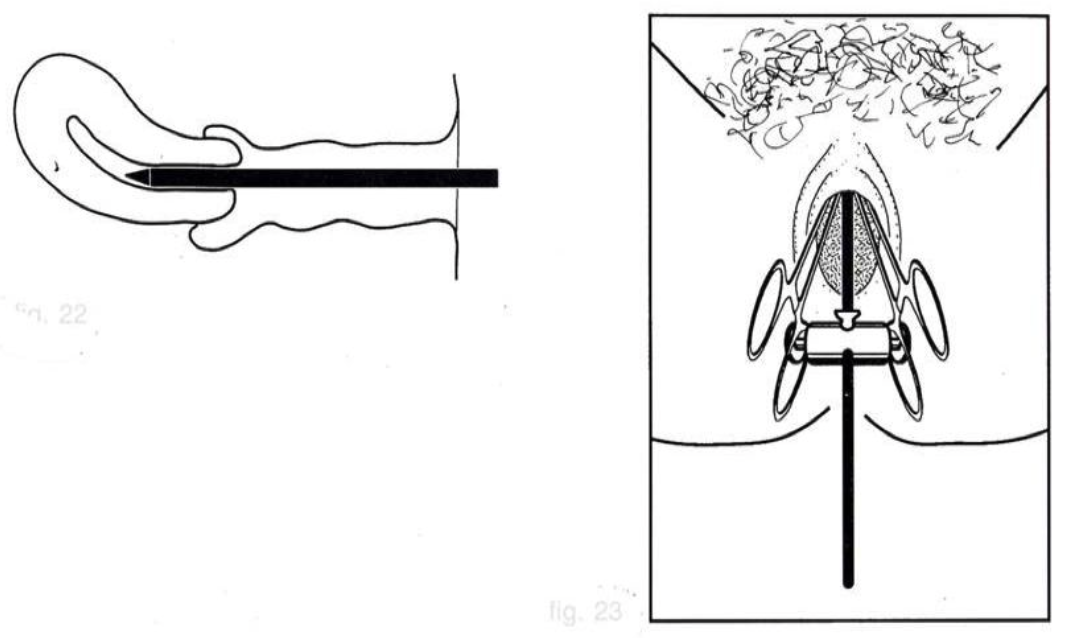

This coring involves transvaginal excision of the functional cervical tissue from the muscular and connective tissue components of the uterine cervix. To ensure the safety of this excision without endangering ureters or the uterine artery, it is necessary to manipulate the uterus, which normally lies in an ante- or retroflexed position into a straight position. This is done by introducing a 5-mm perforation rod into the external cervical os and pushing it through the internal os into the endometrial cavity and finally perforating the uterus in the middle of the fundus. Even in cases of large uterine fibroids, it is possible to safely insert the guide rod and find the uterine cavity. The coring out of a tissue cylinder is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Insertion of CURT Set and Coring.

Figure 2. Insertion of CURT Set and Coring.

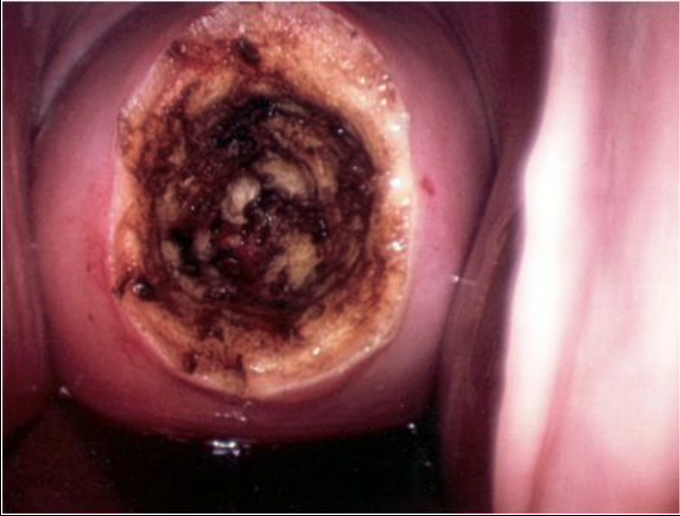

Once a straight line has been established between the cervical canal and the uterine fundus, a preselected CURT may be applied over the perforation rod to cut out the appropriate cylinder of tissue leaving the cervical outer shell intact. The transition zone and endocervical canal can also be removed alternatively by using high cervical conization that is especially useful in patients who have distortion of the cervical os secondary to multiple child births (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Cervical conization specimen.

Figure 3. Cervical conization specimen.

Figure 4. Cervical stump after conization.

Figure 4. Cervical stump after conization.

Ensuring that the entire endocervical canal and transition zone are removed is the step in the CISH supracervical hysterectomy that makes it different from other supracervical techniques. Four steps characterize the procedure, 2 from the vaginal side and 2 transabdominally.

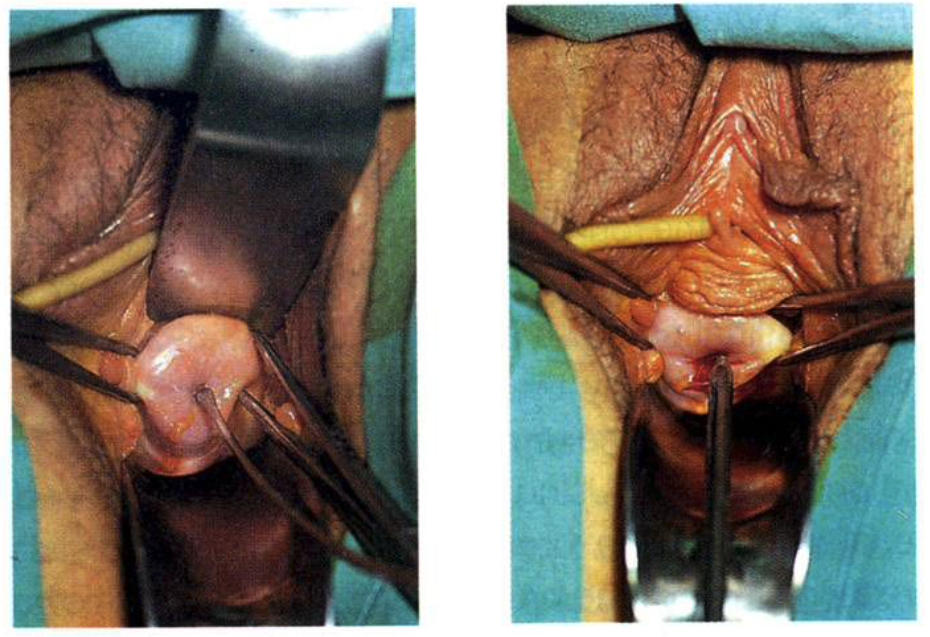

First Vaginal Step

Preoperatively, the vagina is disinfected; the cervix is grasped at 3 and 9 o’clock by 2 single-toothed tenacula. Following this, the uterus length is measured; the cervical canal is dilated up to Hegar 5. A high cervical conization may be performed at this time utilizing electrocautery or the LEEP technique, or the 50-cm long perforation rod is introduced into the uterus to a depth, depending on the uterine length. The perforation rod is part of the CURT set and is fixed vaginally to the previously placed 2 tenacula by using a specifically designed clamp and screw. With large uterine fibroids, this can be difficult and is sometimes more easily performed following transsection of the supracervical uterus. The correct diameter of the CURT is selected based on the ultrasound measurement of the cervix and upon visual inspection. The proper selection of CURT is important, because if the cylinder is too wide, it would cut outside the cervical fascia. A cylinder that is too narrow would not remove all of the functional cervical tissue. The center of fixation of the uterus allows for a 3-dimensional maximal mobilization of the uterus transvaginally (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Vaginal placement of guide rod.

Figure 5. Vaginal placement of guide rod.

Figure 6. Schematic of guide rod placement.

Figure 6. Schematic of guide rod placement.

If the surgeon chooses to perform a high cervical conization, a uterine manipulator, such as the Humi, can be introduced into the endometrial cavity for manipulation of the uterus during dissection. During this procedure, the uterus is continually observed on the video screen.

First Laparoscopic Step

Trocar placement is dependent on surgeon preference. The optic is usually placed in the midline at the umbilicus with 2 lateral ports for instrument placement and possibly a third in the midline just above the pubis.

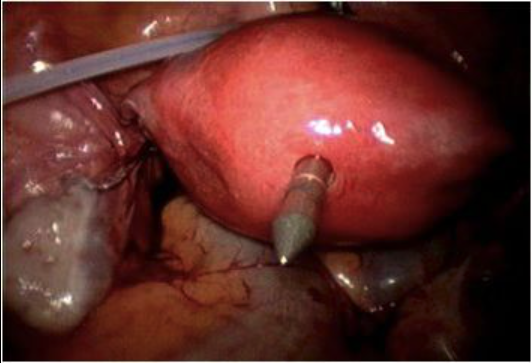

After a clear endoscopic view into the pelvis is established with no bowels adherent to the structures of the uterus, the perforation of the uterine funds by the guide rod is performed under direct vision (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Guide rod perforation of uterus.

Figure 7. Guide rod perforation of uterus.

The uterus can now be anteverted, retroverted, and lateralized for maximal exposure of the structures to be dissected. The Trendelenburg position and utilization of an angled laparoscope assist in exposure of the pelvis and related structures as well.

The adnexa are separated from the pelvic sidewall by using ligatures, sutures, staplers, ligasure, ultrasound, or whatever hemostatic technique is available. When the stapling device is used, placement of the stapler in the suprapubic midline port with mobilization of the uterus to the contralateral side where the stapler is to be applied, allows for good visualization of the lateral pelvic sidewall to ensure that no structures are included in the stapler that could be damaged when the device is fired. Separation of the adnexa usually causes minimal blood loss. The round ligament is also coagulated and divided. This dissection of the adnexa and round ligament leads to an opening of the vesico-vaginal fold and to an opening of the posterior leaf of the broad ligament. This dissection is usually done sharply by using scissors with minimal cautery, while elevating the uterus out of the pelvis. The minimal dissection needed in this area makes injury of the bladder less likely, but this can be difficult in patients who have had a prior caesarean delivery.

The first laparoscopic part of CISH consists of the following steps:

- Separation of adnexa and round ligament from pelvic sidewall or uterus;

- Dissection of the vesico-uterine peritoneum, opening of the paravesical space;

- Placement of one cervical loop.

After the cervix is exposed, a Roeder O-PDS loop is loosely placed around the isthmus of the cervix ready to be locked after the CURT cylinder is removed. This prevents gas leakage and controls bleeding in the remaining cervical stump (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Roeder loop around cervix.

Figure 8. Roeder loop around cervix.

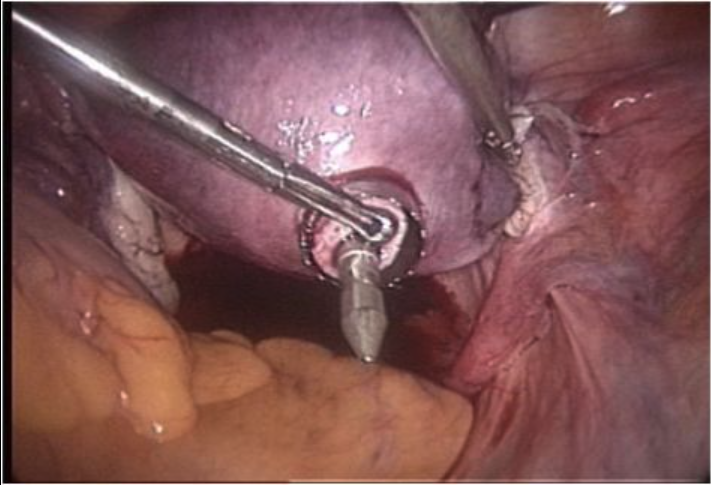

Second Vaginal Step

The fixing screw holding the axial guide rod of the CURT is removed. The cutting tube around the central cylinder is placed as a unit over the axial guide rod, and the chosen cylinder is cored out electrically or manually under endoscopic vision. The tenacula placed at 3 and 9 o’clock are gently pulled, and the motor drive is slowly advanced. An equal pressure is applied to the cutting tube as it is rotated and advanced from the cervix through the endometrium to the fundus. As the cutting tube advances, the calibrated scale along the central cylinder slowly reveals the depth of tissue already cut.

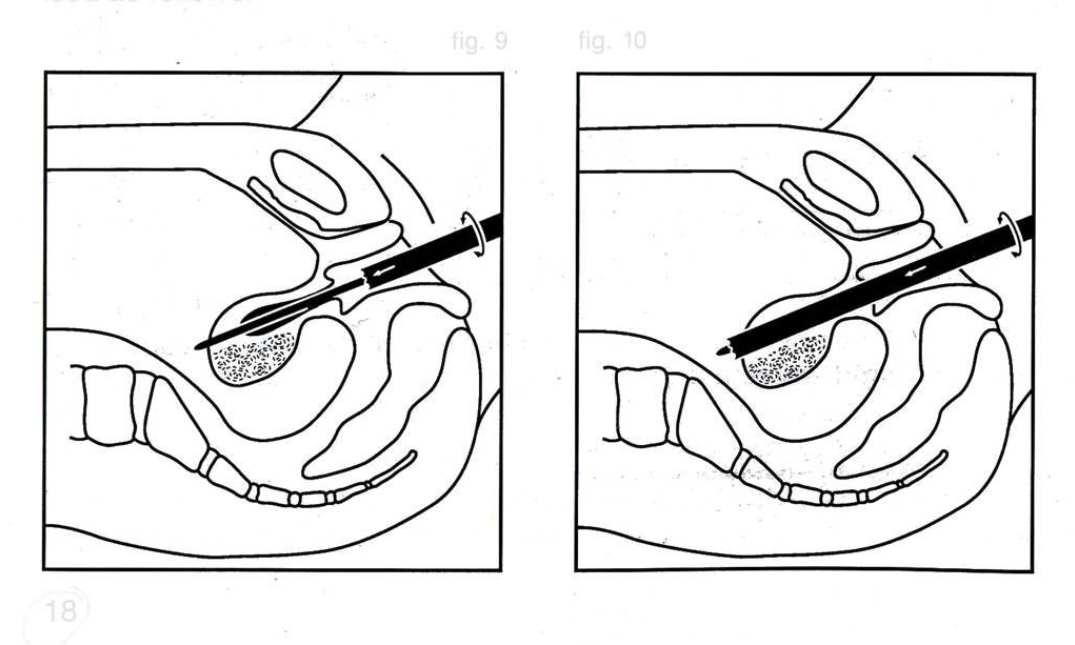

The cutting tube is rotated and slowly cores out a cylinder through the fundal serosa. It is important to ensure that each last thread of tissue has been cut; otherwise, the tissue cylinder cannot be removed transvaginally (Figure 9).

Figure 9. CURT set coring of uterine cavity.

Figure 9. CURT set coring of uterine cavity.

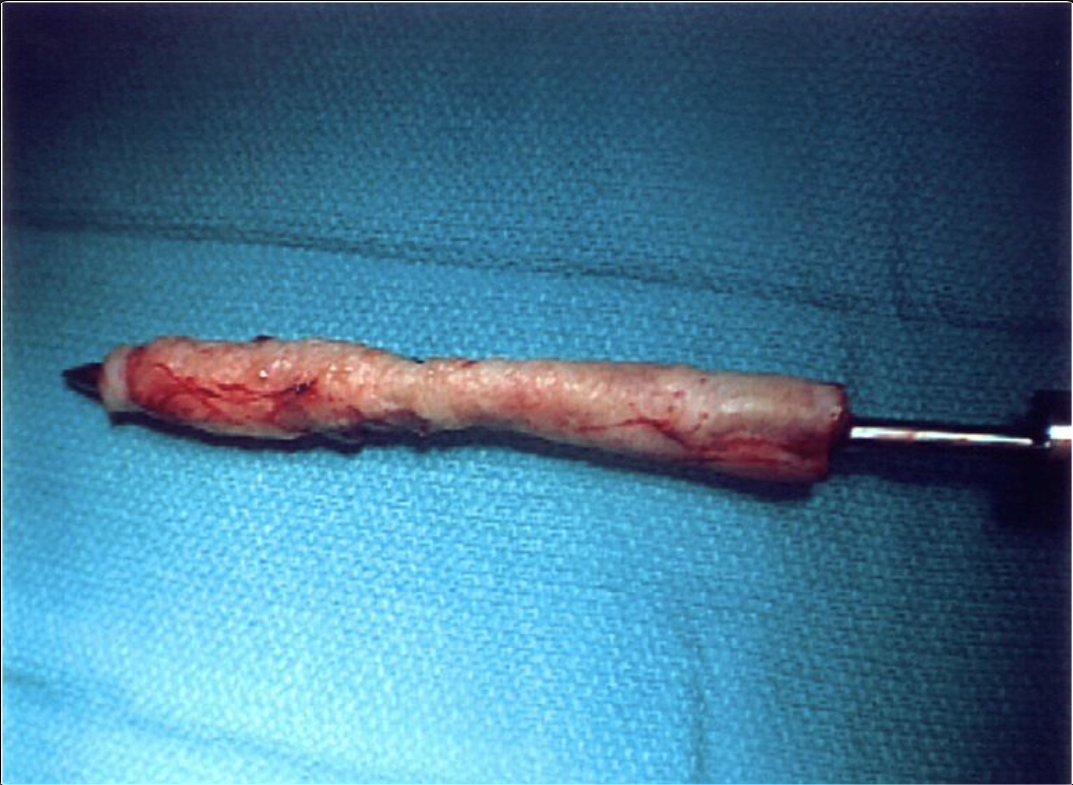

After the tissue cylinder has been completely cored out, it is carefully withdrawn and extracted through the vagina under transabdominal laparoscopic control (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Uterine coring specimen.

Figure 10. Uterine coring specimen.

The endocervical wound is coagulated up to a maximum of 2.5cm into the resection canal. After the CURT cylinder has been resected, there is very little bleeding; however, as a prophylaxis against later bleeding, the inner part of the remaining cervical cylinder has to be coagulated, preferably with an endocoagulator at 120°C or with bipolar coagulation forceps.

In patients who have an extremely large uterus and the guide rod and CURT set are not long enough to reach the fundus of the uterus, an alternative approach makes CISH feasible laparoscopically. After the lateral aspects of the uterus are cleared and the bladder flap created, an O-PDS suture is inserted into the abdominal cavity brought around the cervical isthmus and back out of the abdomen, and an extracorporeal Roeder knot tied and secured at the cervical isthmus. The uterine body can then be cut from the cervix, the ascending branches of the uterine artery individually ligated with Endoloops, and the previously placed O-PDS suture cut and removed. This achieves adequate hemostasis, and an O-PDS Endoloop can then be reapplied at the cervical isthmus, and the coring of the endocervical canal can proceed as described above with the CURT set.

If the CURT set is not used, the remaining endometrial and endocervical canal can be removed from the abdomen by using cautery after a high cervical conization. This accomplishes the complete removal of the transition zone and endocervical canal, the integral unique part of the CISH procedure.

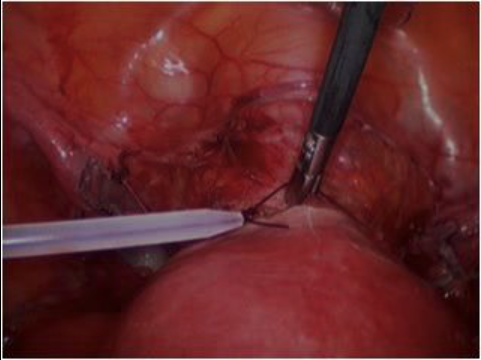

Second Laparoscopic Step

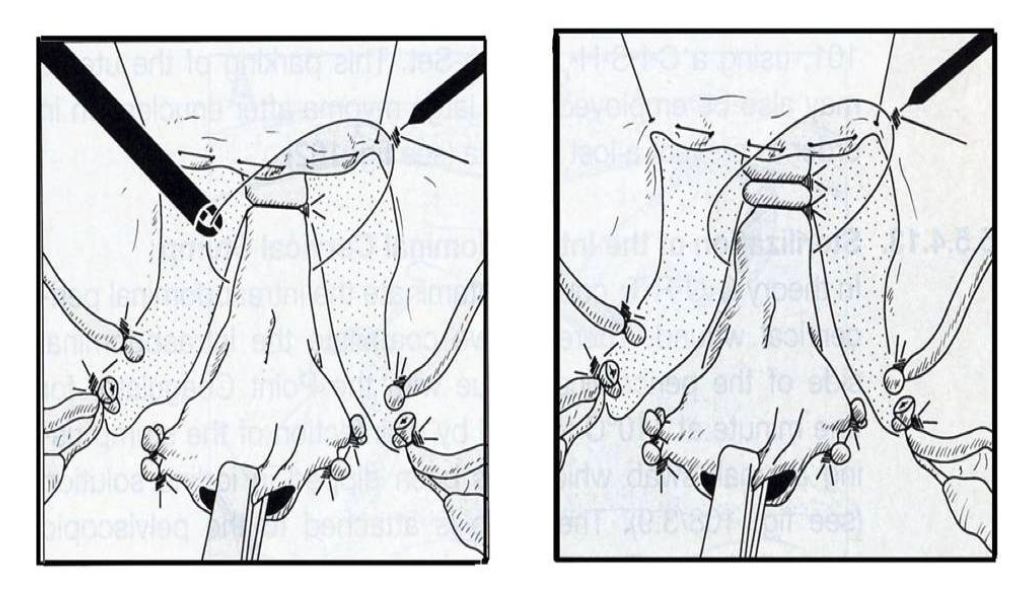

With a 10-mm claw forceps, the uterus is grasped and pulled in the direction of the umbilicus. The prepositioned Roeder loop is placed as deep as possible and closed similar to a tourniquet around the cervix (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Placement of Roeder loop at cervix.

Figure 11. Placement of Roeder loop at cervix.

This technique was already recommended by Rubin in 1951 as a temporary ligature around the ascending branches of the uterine artery for myoma enucleations.

The Double Cervical Ligature

A subsequent ligature is placed over the cervix to closely tie the ascending branches of the uterine artery and its collaterals. If the ligature is not set tightly enough, it is possible that after resecting the uterus, the fascial tissue could invaginate and loosen the ligatures securing the uterine arteries. The cervical stump can be left open for healing by secondary intention, or bleeders coagulated and the defect sutured with absorbable suture. Use of polyglactin suture allows good closure of the stump, reduces the incidence of significant early postoperative bleeding, and is usually absorbed within 4 weeks.

Vasopressin solution can be injected into the cervix before resection as an aid to hemostasis. The incidence of early (<21 days) bleeding requiring intervention is low (1.5%) and is usually handled with topical hemostatics or packing.10

Resecting the Uterus

When the pericervical fascial tissue has been ligated by using the double loop ligation technique, the uterus is regrasped with the forceps and pulled in the direction of the umbilicus. It may then be resected with a monopolar loop above the ligatures, with hook scissors, a laser, or a monopolar current hook. The remaining stump should be at least 2cm to 3cm.

Sterilization of the Intraabdominal Cervical Stump

Disinfection is performed with iodine, and the bipolar forceps are applied to coagulate the surface of the stump.

Peritonealization

When the cervical stump clearly shows the ascending branches of the uterine artery, these may be coagulated and the tourniquet released if desired. The 2 remaining PDS threads may remain on the cervical isthmus and are not a hindrance. The stump may be covered by placing the vesicouterine peritoneum over the tissue pedicles. In addition, the round ligaments may be sutured to the cervical stump intraabdominally to aid in support of the cervical stump and thus support of the vagina. This step is not necessary, but does add extra security for vaginal support. The reperitonealization step is also optional but does close the cervical stump intraabdominally, reducing exposure to dense adhesion formation from bowel to the cervical myometrium (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Reperitonealization.

Figure 12. Reperitonealization.

The pelvis is then irrigated with 1 liter to 2 liters of Ringer’s lactate, and a careful supervision of the whole abdomen is carried out.

Morcellation of the Uterus

The large claw forceps grasp the uterus that is then morcellated from the left lateral incision point through the morcellator. We usually dilate up to the required morcellator size. The Storz Rotocut is ideal for this purpose. It is imperative that all of the myometrial tissue be removed during and after morcellation. There have been reports of severe adhesions and abscess formation in conjunction with retained myometrium. For further hemostasis and adhesion prevention, the remaining cervical stump is coagulated with the bipolar forceps if needed.

The second laparoscopic part of CISH consists of the following steps:

- Closing of 2 ligatures around the cervix;

- Separation of cervix from uterus;

- Coagulation of cervical stump;

- Morcellation;

- Peritonealization of the stump.

Histopathology of CISH Specimens

A normal nonelongated cervix measures 2.5cm to 3cm in length. It is separated into an ectocervix and an endocervix. The ectocervix is covered with stratified squamous epithelium. The epithelium changes from ecto- to endocervix, from a squamous epithelium to columnar epithelium. The epithelium is quite granular, and in the area of the endocervix the so-called endocervical glands may be found.

The cervical sections are analyzed as to whether a hyperplastic cervical mucosa is present and are checked for any remaining glandular components. The distal cervical segment, as it progresses to the isthmus, is analyzed in cross sections. This is performed to demonstrate the outer circumference of the cervix and to allow the pathologist to check for possible mesonephric duct remnants. The uterine cavity segment is also sectioned in a longitudinal manner. The procedure allows for an absolutely correct and accurate histopathological assessment of all the uterine tissue. It is vitally important that the surgeon speaks with the pathologist prior to CISH hysterectomy to inform him or her of the nature of the procedure and the different specimens that will be sent. This also allows for an accurate histological evaluation.

LASH (LAPAROSCOPIC SUPRACERVICAL HYSTERECTOMY) TECHNIQUE

For the LASH technique, only a few reusable instruments are necessary: bipolar coagulation clamp or any other modern hemostasis technology, such as thermofusion and UltraCision, scissors, 2 to 3 grasping forceps, needle holders, a unipolar hook or loop as well as a suction-irrigation system. Let us describe here the simple procedure of using bipolar forceps and subsequent dissection with the hook scissors:

- Positioning of an intrauterine manipulator for the circular movement of the uterus;

- Mobilization of the uterus by coagulating the round ligament, the fallopian tubes, and the ovarian ligaments. In those cases that include bilateral adnexectomy, the infundibulo- pelvic ligament is also coagulated. Coagulation is followed by dissection with the hook scissors;

- Incision of the bladder peritoneum and delineation of the peritoneum by undermining and cutting the peritoneum with scissors. The bladder is pushed caudally;

- Coagulation and dissection of the ascending branches of the uterine vessels;

- Final pushing away of the bladder and dissection of the upper third of the uterine body, cranial to where the uterosacral ligaments leave the cervix;

- Step-by-step dissection of the cervix with a unipolar hook. Smoke can be evacuated by using the suction tube. Constant application of bipolar forceps for hemostasis. It is sometimes difficult to identify the cervical canal. In these cases, the uterus has to be rotated;

- Final suction-irrigation and coverage of the cervical stump with peritoneum by means of a continuous purse-string suture, including the uterosacral ligaments. If the peritoneum is not closed, a stitch is not necessary, because the ligaments have not been detached from the cervical stump;

- Morcellation: The uterus is morcellated by using one of the modern electronic morcellators, available in diameters between 10mm and 25mm, and equipped with a protective shield.

The individual steps are described in the attached video. The LASH technique has the advantage of being easy, safe, and not a lengthy procedure. It provides a minimally invasive alternative to all other methods of total hysterectomy in benign conditions, and has a low perioperative morbidity.10-21

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Experience with CISH now dates back to 1990. The technique is easy to perform, can be carried out on smaller and larger uteri, and leaves the pelvic floor intact. It has a short rehabilitation time and high patient acceptance. It is very cost effective and has a low complication rate.9-14

CISH is an advanced laparoscopic procedure that is initially technically challenging but has a quick learning curve. It can be easily performed by 2 surgeons with 3 hands for the surgery and 1 hand to hold the camera. Every evaluation postulates that patients undergoing laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy compared with total hysterectomy have shorter operation times, shorter hospital stays, and less morbidity than those who underwent laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy.15 The practice of routine cervicectomy at laparoscopic hysterectomy should be reconsidered. In 2001 Okara et al14 published data related to the cervical stump, requiring further surgery following a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. These data, however, could not be verified in our own retrospective evaluation11,15 or in data published by colleagues using the LASH technique.16,17 In the series reported by Morrison and Jacobs in 2001,10 the procedures that were done to the cervical stump after CISH were few (<1.5%) and usually minor in nature. LASH is an easier surgical method than CISH is and fulfils the same purpose. Thus, CISH can be considered a simple subtotal hysterectomy. It has all the advantages of a subtotal hysterectomy and additionally includes the coring of the inner cervix.10 This prevents the occurrence of cervical stump cancer, which after CISH only appears in 1 of 5 million cases.

Surgical complications and clinical outcome proved to be acceptable even in large uteri.18,19 In cases of large uteri, the procedure is possible via laparoscopy. Uterus and fibroids are dissected and morcellated in situ.

In a random evaluation of 253 nonselective cases, the entire excoriated tissue cylinder specimens obtained at hysterectomy in our department were histologically re-examined. In all cases, the transitional zone, from the ectocervix to the endocervix (from squamous to columnar epithelium) was completely removed. In only 6 cases could endocervical glands be found at the cutting margins (2.3% = 0.02% coincidence). If cervical carcinoma were to develop in all of these cases, the incidence rate of cervical carcinoma post-CISH would be 0.02 cases per 100 000, which is a frequency of 1 in 5 million.

COMPLICATIONS

Because the laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy, and especially the supracervical approach, results in decreased postoperative pain and a quicker return to normal activities, the basic disease process must be considered. Every wound can lead to an infection, hemorrhage, hematoma, or retarded healing. Careful wound handling, precise dissection, and hemostasis are of utmost importance. At morcellation, all of the resected uterus must be removed.

After the surgical intervention, the following complications can occur: tissue damage, abdominal wall injuries, vascular injuries, and visceral injuries. Hemoglobin levels of the patients have to be observed as well as possible infections and perioperative problems. A systematic postoperative examination should be carried out even when the patient is discharged on the day of surgery. After CISH and LASH operations, monitoring by vaginal ultrasonography is necessary after 14 days. The cervical stump with the remaining canal can be well seen by vaginal ultrasonography. In more than 1200 cases, we observed only 2 stump infections and 5 cases of severe bleeding outside of the stump. Seven second-look laparoscopies had to be performed, and in 2 cases an additional coagulation of the remaining cervix was carried out.

As particular complications of LASH and CISH, hematomas have been known to occur after the stump is covered with peritoneum or if the peritoneum is left open. If the peritoneum is closed, it is advisable to leave a small gap on both sides to allow bleeding to drain into the abdominal cavity. A partial closure of the peritoneum appears to be the optimal procedure. In a few cases of LASH and CISH performed on large uteri, a hidden descensus was revealed that in one case required a cervical stump sacropexy.

Long-Term Cervical Stump Issues

Late Bleeding

Bleeding at <30 days is a frequently discussed issue with supracervical hysterectomy. The incidence can range from 0.6% to 25%. In a large series by Morrison and Jacobs,10 5 patients presented with bleeding from the remaining cervical stump, and the time for presentation ranged from 2 years to 5 years postoperatively. Four of these patients underwent surgery, and histologic evaluation of the specimen failed to show any endometrial tissue or other pathologic findings to account for the bleeding. The remaining patient did not wish to have any further surgery.

Chronic Pain

In the cervical stump, chronic pain was seen in 0.6% of patients and resolved with removal of the residual cervical tissue. The patients presented from 1 year to 9 years postoperatively with no pathologic finding at examination found to account for the pain.

Retention of the cervical myometrium could be a source for leiomyoma formation at a later date, and we have seen one patient with leiomyoma found in the cervical stump 6.5 years postoperatively. This was removed without incidence. One patient also presented with endometriosis involving the cervical stump 4 years postoperatively, and this was also successfully removed.

Mucocoele formation of the cervical stump was found in 1.8% of patients at long-term follow-up. These cysts were usually found on routine physical examination with no complaints by the patients. Some patients stated that they felt pressure type symptoms in their pelvis, and these mucocoeles were discovered.

Most of the patients requested marsupialisation of the mucocoele cyst, usually done as an outpatient, and histology of the tissue showed findings consistent with Nabothian cyst formation. There were no recurrences after marsupialisation.

Long-term follow-up of the cervical stump after CISH has demonstrated some issues, but retained cervical myometrium does not appear to be of a significant issue or concern; however, continued long-term follow-up is needed.

Because the uterus has much significance as the “bearer of the fruit of love,” organ- preserving procedures are very important during a female’s reproductive years. If total hysterectomy is not advisable because of morbidity or age, CISH and LASH as the least traumatic minimally invasive operative techniques are carried out to preserve the quality of life. New technologies provide better opportunities for that. Many patients need psychological support. It is of utmost importance to explain to them that with the supracervical hysterectomy a part of the uterus, the cervix, remains. This is particularly important for Arabic women.

To sum up the possibilities of complications, let me clearly express that laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy has fewer complications than total hysterectomy has and is better accepted psychologically by the majority of females; however, it can only be performed if no pathology exists on the cervix.

CONCLUSIONS

Even in the case of uterine fibroids, larger than the 24th gestational week in size, a laparoscopic CISH procedure is possible and a total hysterectomy not indicated. Taking into account the remaining cervical concept, a laparotomic CISH is an alternative procedure for larger fibroids. This alteration of the laparoscopic technique delivers the advantages of pelvic floor and vaginal support, while removing endocervical and endometrial tissue. In these cases, the classic supracervical hysterectomy is first performed by laparotomy, followed by coring of the cervix. The transformation zone is cored out transvaginally using the CURT after the uterus has been subtotally resected.

The advantages of the CISH method using CURT can be summarized as follows:16

Surgical benefits:

- Secure transvaginal coring out of the cervical mucosa including the glandular component;

- Preservation of the cardinal ligament;

- Preservation of the pericervical network of nerves;

- Protection of the ureters, uterine artery, bladder, and rectum, and others;

- No colpotomy;

- The vagina is not shortened;

- No danger of abdominal infection through contamination from vaginal bacteria;

- Elimination of the method with associated secondary healing of the vaginal cuff;

- Minimal traumatization and little blood loss;

- Elective suspension of the ligaments on the cervical fascial stump as opposed to the vaginal cuff.

Medical benefits:

- Prophylaxis against cervical stump carcinoma;

- Complete preservation of the pelvic floor anatomy through preservation of the support function of the cardinal ligament;

- Reduced physical stress for the patient;

- Reduction in the time for convalescence;

- Complete preservation of sexual function with regard to subjective vaginal and cervical components;

- Complete preservation of the functionability of the vagina as regards partner contact;

- Earlier return to sexual activity;

- No change in the perception of sexual contact by the partner.

Psychological benefits:

- Better quality of life through CISH despite hysterectomy;

- Very low incidence of cervical stump carcinoma compared with that in subtotal hysterectomy via laparoscopy without coring of the inner cervix and total hysterectomy.

References

- Freund WA. Bemerkungen zu meiner Methode der Uterusextirpation. Zbl Gynäkol. 1878;2:497-500.

- Tervilä I. Carcinoma of the cervical stump. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1963;42:200.

- Semm, K. Hysterektomie per laparotomiam oder per pelviscopiam. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 1991;51:996-1003.

- Semm K. Morzellieren und Nähen per pelviskopiam – kein Problem mehr. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 1991;51:843-846.

- Semm K. Prophylaxe der Sterilität durch minimal invasive Chirurgie. Der Frauenarzt. 1994;35:944-954.

- Mettler L, Semm K, Shah A, Shah P. Intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy without colpotomy and transuterine mucosal resection by pelviscopy and laparotomy – our first 200 cases. Curr Invest Gynecol Obstet. 1993;9:359-362.

- Mettler L, Semm K, Lüttges J, Panadicar D. Pelviskopische intrafasciale Hysterectomie ohne Kolpotomie (CISH). Gynäkol Prax. 1993;17:509-526.

- Mettler L, Alvarez-Rodas E, Lehmann-Willenbrock E, Lüttges J, Semm K. Intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy without colpotomy and transuterine mucosal resection by pelviscopy and laparotomy. Diagn Therap Endoscosc. 1995;1:201-207.

- Mettler L, Semm K, Lehmann Willenbrock E, Shah A, Shah P, Sharma R. Comparative evaluation of classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy (CISH) with transuterine mucosal resection as performed by pelviscopy and laparotomy – our first 200 cases. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:418-423.

- Morrison JE Jr, Jacobs VR. 437 classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomies in 8 years. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):558-567.

- Mettler L, Semm K. Subtotal versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;164(Suppl):88-93.

- Kim DH, Bae DH, Hur M, Kim SH. Comparison of classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy with total laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5:253-260.

- Lyons TL. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:441-450, ix.

- Okaro EO, Jones KD, Sutton C. Long term outcome following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. BJOG. 2001;10:1017-1020.

- Milad MP, Morrison K, Sokol A, Miller D, Kirkpatrick L. A comparison of laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy vs. laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;3:286-288.

- Mettler Manual for Laparoscopic and Hysteroscopic Gynecological Surgery. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2006.

- Salfelder A, Lueken RP, Bormann C, et al. Die suprazervikale Hysterektomie in neuem Licht. Wiederentdeckung als minimalinvasive Methode. Frauenarzt. 2003;44:1071-1075.

- Bojahr B, Raatz D, Schonleber G, Abri C, Ohlinger R. Perioperative complication rate in 1706 patients after a standardized laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy technique. J Minimal Invas Gynecol. 2006;13(3):183-189.

- Lyons TL, Adolph AJ, Winer WK. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy for the large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:170-174.

- Learman LA, Summitt RLL, Varner RE. A randomized comparison of total or supracervical hysterectomy: surgical complications and clinical outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:453-462.

- Gorlero F, Lijoi D, Biamonti M, et al. Hysterectomy and women satisfaction: total versus subtotal technique. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(5):405-410.