Leiomyomas: Uterine Fibroid Embolization

Mahmood K. Razavi, Mojgan Mohammadi

Uterine leiomyomas are the most common solid tumors in the female reproductive tract, occurring in 20% to 40% of women in the reproductive age. They are highly vascular estrogen-responsive benign tumors and frequently increase in size during pregnancy.

Conditions that cause elevated estrogen levels, such as anovulatory states or granulosa– theca cell tumors, increase the incidence and size of fibroids. After menopause, tumor regression occurs, often leading to calcification.

The majority of fibroids are asymptomatic and in the absence of substantial growth should be treated conservatively. Symptoms may include abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, abdominal distention, and impaired fertility. In addition, compression of adjacent organs may cause symptoms, such as urinary frequency, urgency, constipation, back pain, and radiculopathy. Both patients and physicians frequently overlook the correlation between fibroids and the latter 2 symptoms.

Current therapies offered to patients with symptomatic fibroids include medical and surgical treatments. Medical management consists of GnRH agonists. This treatment reduces estrogen levels, thereby leading to a reduction in fibroid number and size.

However, because of the risk of osteoporosis and development of symptoms of menopause, treatment is recommended only for a short time, and following discontinuation, the symptoms may recur. Surgical therapy has mainly consisted of hysterectomy. Of the more than 600,000 hysterectomies performed in the United States annually, leiomyomas are the most common indication, accounting for approximately one third of the cases. Hysterectomies, however, occur at the expense of fertility and have a long recovery period. Despite the reported low mortality of hysterectomy (0.1%), complications like hemorrhage, peritonitis, sepsis, pulmonary embolism, and injury to bowel, bladder, ureter, or adjacent vessels may occur. Furthermore, removal of the uterus in itself may be emotionally distressful for the patient.

Less invasive uterine-sparing procedures, such as myomectomy, are hence attractive alternatives, particularly for women of childbearing age who desire future pregnancy. Potential disadvantages of myomectomy include the relatively high risk of recurrence of fibroids and uterine wall weakening, which may interfere with future delivery. In addition, surgical complications, such as infection, adhesions, bowel obstruction, infertility, and ectopic pregnancies, may result.

Because of the limitations of these surgical approaches, uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) has emerged as an effective, less-invasive alternative therapy. The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of UFE, including preprocedural evaluation, technical principles, postprocedural monitoring, and clinical results.

EMBOLIZATION

The procedure of therapeutic embolization is not new. It has been used to treat various conditions, such as traumatic bleeds, gastrointestinal bleeds, tumors, vascular malformations, and aneurysms, for the past 3 to 4 decades. More recently, the application of embolization as an adjunct to transvascular targeted drug delivery for treatment of cancer is gaining wide acceptance in the field of oncology.

Various embolic agents are commercially available to achieve the desired clinical effect in the wide variety of pathologies to which embolization is applied. These range from large coils and flow occluders for larger vessels to liquid agents and particles microns in diameter for the treatment of vascular malformations and tumors.

The first reported application of embolization in the obstetric field was in 1979.1 In this case, embolization was used to control postpartum hemorrhage in a patient in whom surgical ligation of the internal iliac arteries was unsuccessful. Since then, embolization has been widely used for various conditions, including postpartum, post-cesarean, or postabortion hemorrhage, as well as pre- and postoperative gynecologic hemorrhage.2

UTERINE FIBROID EMBOLIZATION

The features of uterine fibroids that make them suitable targets for embolization therapy are their vascularity and hormone responsiveness. The arteries feeding the fibroids are typically larger in diameter, are more numerous, and have a lower resistance compared with the normal arteries of the muscle of the uterus (spiral arteries). Embolization takes advantage of this pathologic preferential flow to the fibroids. During the procedure, embolic particles of a particular size are selected to preferentially target the tumor vascularity and its blood supply. This has 2 advantages. First, the resultant ischemia causes coagulative necrosis of the fibroid, leading to a decrease in the size of the tumors. Second, the absence of circulation to the fibroids prevents tumor exposure to the systemic hormones and growth stimuli, such as estrogen. Furthermore, lack of flow results in cessation of fibroid-related bleeding.

In 1995, the first report on the results of the clinical application of uterine artery embolization for fibroids was published in the literature.3 Several other groups reported their results soon after, confirming the technical and clinical merits of this approach.4-8 Since these original publications, there has been a substantial growth in both the clinical volume and scientific evaluation of UFE worldwide.

PATIENT EVALUATION FOR UFE

As with any other medical procedure, the treating physician must perform a complete history and physical examination. Coexistence of other conditions that may cause patients’ symptoms should be investigated. Additionally, comprehensive preprocedural counseling and assessment by the treating physician are essential. Technical details, risks, complications, and postprocedural expectations should be reviewed with patients. Careful assessment of patients’ expectations is essential to establish whether UFE is the appropriate next step.

Medical history, physical examination, imaging, and/or laboratory evaluation are directed toward confirming that symptoms are related to fibroids and ensuring that there are no contraindications to UFE. In addition, a focused vascular examination is also performed. Routine preangiography laboratory tests, such as serum electrolytes, renal panel, and complete blood count, also are obtained.

Contraindications

Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication to UFE. Embolization for the treatment of fibroids should also be avoided in the setting of known or suspected pelvic malignancy. Although frequently used for palliation, embolization is not a replacement for surgery in such cases. Active infection is also a contraindication to UFE, because of the increased risk of abscess formation. With the exception of adenomyosis, UFE may not be of much benefit if the symptoms are the result of causes other than fibroids. Patients must also be evaluated for any contraindications to angiography.

Relative contraindications include presence of large submucosal or pedunculated large subserosal fibroids, desire for cosmetic relief, and unrealistic patient expectations.

Imaging

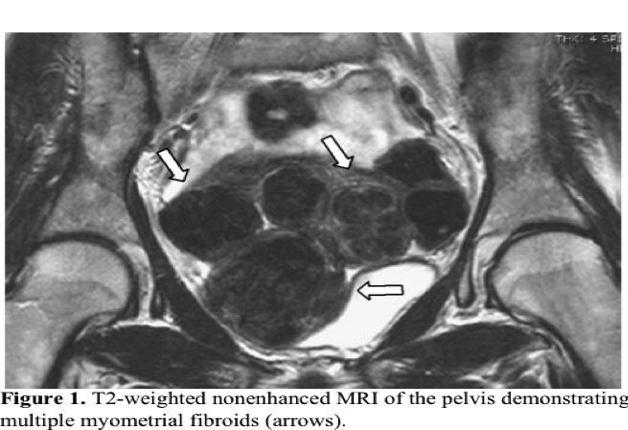

Because of its superior soft tissue resolution, MRI is the imaging modality of choice for women undergoing evaluation for UFE.

Office ultrasound is an insufficient imaging tool for this purpose. MRI confirms the presence of fibroids and provides information on other anatomic and physiologic features that are important correlates of UFE outcome, such as the precise location of the fibroids, degree of vascularity and extrauterine blood supply, and presence of spontaneous infarction (Figure 1). Additionally, other causes of pelvic pain, menorrhagia, uterine/abdominal enlargement, and compression syndrome are excluded. Similarly, uterine volume and other uterine pathologies, such as adenomyosis and malignancy, are better evaluated. Limitations of MRI include increased cost and longer scan duration.

Additionally, claustrophobic patients may have difficulty completing the examination.

UFE TECHNIQUE

Performing UFE requires complete familiarity with angiographic principles and techniques, vascular anatomy of the pelvis and uterus, and the procedure of embolization. Hence, physicians experienced with UFE obtain the best outcome.

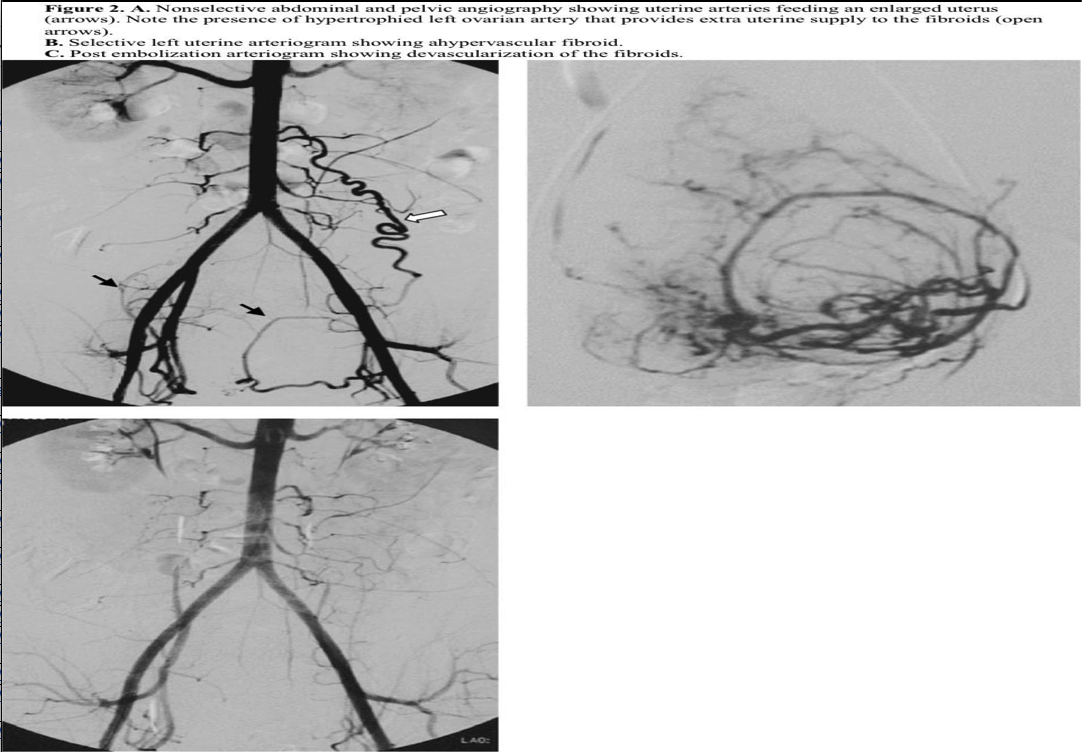

The procedure is most commonly performed by placing a standard 5F introducer sheath in one of the common femoral arteries. A nonselective pelvic arteriogram should first be obtained to evaluate the number and size of the arterial feeders to the uterus and fibroids. This is usually accomplished by placing a pigtail catheter at the level of the renal arteries and performing digital subtraction angiography (Figure 2). An initial nonselective injection of contrast typically identifies any potential ovarian or other extrauterine blood supply to the fibroids. Uterine arteries are then selected individually using one of many selective catheters (Figure 2). In cases of uterine arteries with a small caliber or very tortuous proximal course, microcatheters are used in a coaxial fashion. The catheter tip is usually placed in a position distal to the cervicovaginal branch of the uterine artery, and embolic particles are injected.

The choice of embolic particle size depends on the type of particle chosen. A variety of embolic particles and sizes are available for this purpose. The most common embolic agents used are either polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or trisacryl gelatin microsphere (Embosphere, BioSphere Medical, Rockland, MD, USA). These are considered to be permanent embolic particles that preferentially reside in the microvasculature of the tumor and occlude the flow.

The commonly accepted end point of embolization is stasis of flow in the main uterine arteries (Figure 2).

Following adequate embolization, the catheter and introducer sheath are removed and hemostasis obtained at the puncture site.

EFFICACY OF UFE

A high technical success rate has been reported for UFE, exceeding 98%. Technical success rate is defined as the ability to catheterize and embolize the fibroid blood supply. Clinical efficacy of UFE in the early studies was reported to be between 80% and 95% and depended on the nature of the symptoms.4-9 Relief from menorrhagia has the highest consistent success rate of 90% to 95% with UFE and is immediate. This is hardly surprising, because fibroids become devoid of vasculature after UFE. Recurrence of pelvic bleeding may be the result of incomplete embolization of the existing fibroid, presence of extrauterine blood supply, growth of new fibroids, or causes other than myomas.

Resolution of dysmenorrhea and bulk-related symptoms has been reported to be in the 80% to 90% range. The potential reasons for lack of complete response in these patients are discussed below.

In a recent study of 2112 eligible patients, a change in symptom severity and health- related quality of life among patients treated with UFE was reported.10 At 12 months, symptom improvement was observed in 94.53% of patients, with the mean symptom score improving from 58.61 to 19.23 (P=0.001). The mean health-related quality-of-life score improved from 46.95 to 86.68 (P=0.001). Hysterectomy was required in only 2.9% of patients in the first 12 months.

Reduction in the volume of the fibroids depends on the tumor’s initial size, vascularity, and presence or absence of previous spontaneous infarcts. It averages around a 50% to 60% decrease in volume and is continuous over time, with the maximum rate of shrinkage occurring in the first 6 to 12 months postembolization.8 The degree of reduction in the volume of leiomyomas after UFE is unpredictable and cannot be guaranteed in any one patient. For this reason, we recommend surgery to women who seek cosmetic relief from fibroids. Despite the emphasis of many physicians and patients on the size of fibroids, there appears to be no correlation between reduction in fibroid volume and degree of relief from symptoms after UFE.

Studies addressing the long-term efficacy of UFE have confirmed the durability of this procedure in patients with symptomatic fibroids. Spies et al11 followed 200 consecutive patients who had undergone UFE. Of the 182 patients with complete follow-up data, 73% remained symptom-free at 5 years.

Although UFE results in a decrease in fibroid size and stops the pathologic preferential flow away from the muscle of the uterus, its role in the treatment of fibroid-related infertility has not been comprehensively studied to date. For this reason, UFE is not recommended for treatment of infertility until more data become available.

CAUSES OF UFE FAILURE

Clinical failure of UFE occurs in a relatively small number of patients. There are several causes for failure, including coexistence of other pelvic pathologies not responding to UFE, unrealistic patient expectations, and inadequate embolization leading to suboptimal fibroid infarction, which may be the result of extrauterine arterial flow to the fibroids.

Ovarian arteries are the most important source of such collateral flow.

The majority of vascular communications between the uterus and ovary are too small to be visualized at angiography and do not affect the outcome of UFE. However, 3 main types of ovarian-to-uterine artery anastomosis that are of prognostic significance have been described at angiography.12

The most common anastomosis is type I, which occurs in approximately 28% of women with symptomatic fibroids. The ovarian artery connects to the intramural uterine artery via the tubal segment, with flows toward the uterus. Type I anastomosis is a substantial source of collateral flow to the uterus and fibroids. In this type, ovarian artery supply is not a likely source of UFE failure, because the embolization typically occurs distal to the point anastomosis. Fibroid devascularization is hence unaffected. Disruption of flow at any point proximal to these anastomoses, which may occur with uterine artery ligation, will not cause fibroid infarction and lasting symptom relief in women with this type of anastomosis.

In type II anastomosis, direct parasitization of the flow from the ovarian arteries to the fibroids occurs. Although connections to the intramural uterine artery may exist, flow to the fibroid is anatomically independent of uterine artery. This occurs in approximately 8% of women and may be an important cause of procedural failure after UFE.12

Conversely, in type III anastomosis, the ovarian supply is mainly from the uterine artery through the tubal arteries. Independent ovarian arteries are not seen. At angiography, the observed flow is therefore toward the ovary. This pattern of flow has been observed in approximately 6% of arteries. This pattern of flow will not change the efficacy of fibroid devascularization but may be a cause of ovarian failure.

UFE VERSUS SURGERY

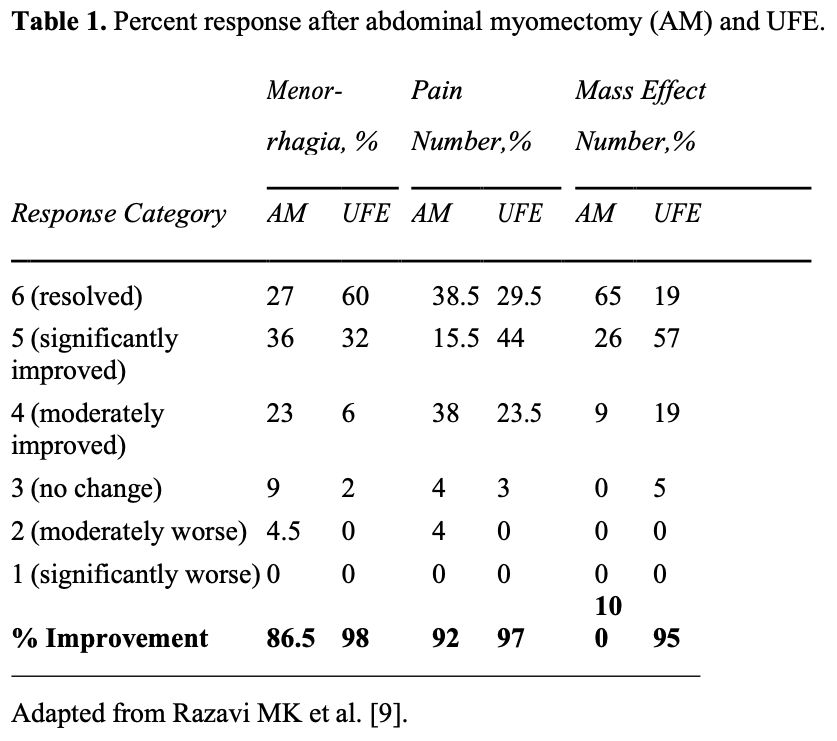

Several studies have compared UFE with surgery, either abdominal myomectomy or hysterectomy. In the first such study, the outcomes of 2 uterine-sparing procedures (UFE and abdominal myomectomy) were retrospectively compared in 111 patients.9 Efficacy, complication, and recovery periods were the main study outcome measures of this analysis. Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Statistical analysis of these results revealed that UFE is significantly better than myomectomy in relieving menorrhagia, with both procedures being equally effective in controlling pelvic pain. There was a trend toward better improvement in symptoms of mass effect, such as urinary frequency and constipation, after myomectomy.

Comparison of other outcome measures, such as postprocedural pain, recovery period, and complications, all favored UFE (Table 2). The need for secondary interventions during the study period was similar in both groups.

The complications included nonautologous blood transfusion (n=3), wound infection (n=2), adhesion (n=2), readmission for ileus (n=1), and chronic pelvic pain (n=2) among the myomectomy patients. Complications in the fibroid embolization group included endometritis requiring readmission for intravenous antibiotics (n=1), readmission for pelvic pain (n=1), and menopause (n=4). All those who experienced menopause after fibroid embolization were older than 46 years.

In a prospective randomized study of 63 women with intramural fibroids >4cm who desired future fertility, Mara et al13 compared UFE with myomectomy. Similar to the study by Razavi et al,9 UFE was associated with fewer hospital days, procedure time, blood loss, and disability period. Complication rate and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were similar at 6 months, although the UFE group reported a lower rate of symptom relief.

UFE has also been compared with hysterectomy. Pinto et al14 conducted a prospective analysis of hysterectomy versus UFE in 60 patients. UFE was associated with fewer complications and a shorter hospital stay. Spies et al,15 in a prospective multicenter trial of UFE versus hysterectomy, reported similar results. In this study, pain relief was more common among those with hysterectomy, with both groups experiencing marked improvement in other symptoms and quality-of-life scores, with no difference between them. Complications were more frequent in the hysterectomy group (50% vs. 27.5%). In a cost-effectiveness analysis, Beinfeld et al16 developed a decision model to compare the costs and effectiveness of UFE and hysterectomy. They concluded that UFE is less expensive and more effective than hysterectomy. In their model, however, when the quality-of-life adjustment was eliminated, the 2 procedures were equally effective.

UFE AND PREGNANCY

The issue of pregnancy after UFE has been addressed in only a small number of studies. Kim et al17 reviewed their experience in 94 patients and concluded that UFE with PVA particles does not seem to affect fertility among women who do not use contraception.

Based on their study of 671 women who underwent UFE, Carpenter et al18 observed no increased obstetric-associated risk, with the exception of the number of patients who underwent cesarean deliveries. In a similar large multicenter clinical registry of 555 patients with a mean age of 43 years, the enrolled women were followed prospectively.19 Thirty-one percent of the patients were younger than 40 years. Although it is unclear as to what fraction of women who were trying to get pregnant actually did, 24 pregnancies were reported in women who were an average age of 34 years. There were 4 spontaneous abortions and 4 preterm deliveries. Abnormal placentation was seen in 3 women. The authors concluded “women are able to achieve pregnancies after uterine artery embolization, and most resulted in term deliveries and appropriately grown newborns.” Close monitoring of placental status, however, was recommended in this study.

In comparison with myomectomy, McLucas et al20 and Goldberg et al21 reached opposite conclusions. The McLucas group observed no difference in pregnancy outcome between those who underwent UFE versus those who had myomectomy, whereas the Goldberg group reported a higher incidence of complications in UFE patients. It should be noted that both these studies suffer from major methodologic flaws, and their results should be interpreted with caution.

COMPLICATIONS OF UFE

Serious complications after UFE are rare. In a large prospective multicenter study of 3160 patients enrolled in 72 sites, major in-hospital complications occurred in 0.66% of patients.22 The 30-day complication rate was 4.8%, with no reported deaths. The most common complication was inadequate pain control requiring a hospital visit by 2.4% of patients. One percent required additional surgical procedures within the first 30 days, with 0.1% undergoing hysterectomy. Multivariate analysis showed modest increased odds for an adverse event for African Americans, smokers, and those with prior leiomyoma procedures.22

Endometritis has been reported to occur in 1% to 4% of patients after UFE. The most common risk factors for infection are the presence of large submucosal fibroids or the preexistence of an undetected or incompletely treated pelvis infection. In these patients, aggressive therapy with antibiotics is warranted to prevent further progression, which may lead to sepsis and/or hysterectomy.

A long-term complication of UFE is ovarian failure and early menopause. The risk of ovarian failure is age dependent and highest in women over the age of 45. Review of the literature reveals that <1% of women under the age of 40 develop menopause after UFE. This risk increases to 15% for those older than 45 years.12,23

Other, less common complications occurring in <1% of patients include vessel injury, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.

POSTPROCEDURAL CARE AND FOLLOW-UP

As mentioned above, the most common reason for postprocedural physician visits after UFE is inadequate pain control. Because of the less invasive nature of UFE, occasionally the treating physicians have a tendency to underprescribe pain medications. According to the published studies, women will experience pelvic discomfort for an average of 3 to 4 days after the procedure and may require oral analgesics. The degree of pain is highly variable, with no reliable preprocedural indicator. Rarely, pain may last longer, but persistent pelvic discomfort for a period longer than 3 weeks or recurrence of pain after an initial abatement requires evaluation.

Postembolization syndrome is a constellation of symptoms including nausea, low-grade fever, and malaise, and is common after UFE. This syndrome may last for 4 to 7 days postprocedure, and the treatment is supportive, including the use of antiemetic and anti- inflammatory medications.

A self-limiting vaginal spotting with a brownish discharge is also a common finding and may occur for several weeks after embolization. In fewer than 10% of women, the discharge may be associated with passing of tissue and clot, which have been shown histologically to be fibroid fragments. Transcervical expulsion of leiomyomas may occur in 1% to 2% of patients and is associated with pain and bleeding. These are typically submucosal fibroids, which detach into the uterine cavity about 4 to 12 weeks after embolization. Incomplete passage is associated with a high risk of infection and may require hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics. Delayed passage of leiomyomas for up to a year after UFE has also been reported.24

After the initial postprocedural follow-up, patients are seen in follow-up approximately 3 months later. Follow-up MRI is obtained 6 to 12 months later.

Temporary amenorrhea occurs in approximately 5% to 8% of women during the first 3 months following the procedure. Menses resumes in the majority of these women, with no permanent sequela. No specific therapy is prescribed in these patients. If amenorrhea persists, a serum FSH may be obtained to evaluate for menopause.

Myometrial pregnancy represents a rare subtype of ectopic pregnancy. Leyder et al25 reported a case of intramyometrial ectopic pregnancy in an ICSI patient following uterine artery embolization.

Although the presence of an intrauterine device (IUD) has been traditionally considered a risk factor for post rocedural infection in patients undergoing uterine artery embolization (UAE), presence of an IUD might not be considered a contraindication for UAE.26

SUMMARY

UFE is a uterine-sparing alternative to hysterectomy that has been shown to be an effective therapy for women with fibroids. By permanently eliminating the blood flow to the fibroids, UFE alleviates symptoms and reduces fibroid volume and uterine size.

Advantages include the elimination of surgical risks, treatment of the entire fibroid burden with one therapy, preservation of fertility, and reduction of hospitalization and recovery times. Although the role of UFE in the treatment algorithm for leiomyomas remains controversial, it should be offered to women who do not desire surgery or those who have failed medical or less-invasive surgical therapies before hysterectomy is advised.

References

- Brown BJ, Heaston DK, Poulson AM, Gabert HA, Mineau DE, Miller FJ Jr. Uncontrollable postpartum bleeding: a new approach to hemostasis through angiographic arterial embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54(3):361-365.

- Vedantham S, Goodwin SC, McLucas B, Mohr G. Uterine artery embolization: an underused method of controlling pelvic hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(4):938-948.

- Ravina JH, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, et al. Arterial embolisation to treat myomata. Lancet. 1995;346:671-672.

- Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, Kim J, Levy EB, Gomez-Jorge J. Uterine artery embolization for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:29-34.

- Goodwin SC, McLucas B, Lee M, et al. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata: midterm results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1159-1165.

- Worthington-Kirsch RL, Popky GL, Hutchins FL Jr. Uterine arterial embolization for the management of leiomyomas: quality-of-life assessment and clinical response. Radiology. 1998;208:625-629.

- Hutchins FL Jr, Worthington-Kirsch R. Embolotherapy for myoma-induced menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:397-405.

- Spies JB, Roth AR, Jha RC, et al. Leiomyomata treated with uterine artery embolization: factors associated with successful symptom and imaging Radiology. 2002;222:45-52.

- Razavi MK, Hwang G, Jahed A, Modanloo S, Chen B. Abdominal myomectomy versus uterine fibroid embolization in the treatment of symptomatic uterine AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(6):1571-1575.

- Spies JB, Myers ER, Worthington-Kirsch R, Mulgund J, Goodwin S, Mauro M; the FIBROID Registry Investigators. The FIBROID Registry: symptom and quality-of-life status 1 year after therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1309-1318.

- Spies JB, Bruno J, Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Magee ST, Ascher SA, Jha RC. Long- term outcome of uterine artery embolization of leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5):933-939.

- Razavi MK, Wolanske K, Hwang G, Sze D, Kee S, Dake M. Angiographic classification of ovarian to uterine artery anastomoses: incidence and significance in UFE. Radiology. 2002;294:707-712.

- Mara M, Fucikova Z, Maskova J, Kuzel D, Haakova L. Uterine fibroid embolization versus myomectomy in women wishing to preserve fertility: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126(2):226-233.

- Pinto I, Chimeno P, Romo A, et al. Uterine fibroids: uterine artery embolization versus abdominal hysterectomy for treatment – a prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trial. Radiology. 2003;226(2):425-431.

- Spies JB, Cooper JM, Worthington-Kirsch R, Lipman JC, Mills BB, Benenati JF. Outcome of uterine embolization and hysterectomy for leiomyomas: results of a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):22-31.

- Beinfeld MT, Bosch JL, Isaacson KB, Gazelle GS. Cost-effectiveness of uterine artery embolization and hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. Radiology. 2004;230(1):207- 213.

- Kim MD, Kim NK, Kim HJ, Lee MH. Pregnancy following uterine artery embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles for patients with uterine fibroid or adenomyosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28(5):611-615.

- Carpenter TT, Walker WJ. Pregnancy following uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: a series of 26 completed pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(3):321-325.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, Vilos G, Common A, Vanderburgh L; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):67-76.

- McLucas B, Goodwin S, Adler L, Rappaport A, Reed R, Perrella R. Pregnancy following uterine fibroid embolization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74(1):1-7.

- Goldberg J, Pereira L, Berghella V, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after treatment for fibromyomata: uterine artery embolization versus laparoscopic myomectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):18-21.

- Worthington-Kirsch R, Spies JB, Myers ER, et al; FIBROID Investigators. The Fibroid Registry for outcomes data (FIBROID) for uterine embolization: short-term outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):52-59.

- Chrisman HB, Sakter MB, Ryu RK, et al. The impact of uterine fibroid embolization on resumption of menses and ovarian function. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:699-703.

- Spies JB, Spector A, Roth AR, Baker CM, Mauro L, Murphy- Skrynarz K. Complications after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):873-880.

- Leyder M, De Vos M, Popovic-Todorovic B, Dujardin M, Devroey P, Fatemi, Intramyometrial ectopic pregnancy in an ICSI patient following uterine artery embolization. Reprod. Biomed Online. 2010, Jun 20(6):831-835.

- Smeets, AJ, Nijenhuis RJ, Boekkooi PF, Vervest HA, van Rooij WJ, Lohle PN. Is an intrauterine device a contraindication for uterine artery embolization? A study of 20 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010 Feb;21(2):272-274.