Hysteroscopy: Evaluation and Management of the Uterine Septum

Sumathi Kotikela, Eric J. Bieber, Han Ying, Edie L. Derian

Uterine anomalies are a relatively common congenital abnormality, with uterine septum being the most common.1This is even truer in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss, in whom rates of uterine abnormalities may approach 15% to 27%. Historically, the uterine septum has been approached via laparotomy through either a Tompkins or Jones procedure. These successful, but highly morbid, procedures require laparotomy with significant hospital stays, subsequent cesarean delivery, and have carried a high risk of adhesion formation. More recently, this surgery has been supplanted by hysteroscopy or other minimally invasive methodologies. This section focuses on the embryologic development of the genital tract that may lead to müllerian abnormalities. It also discusses the workup of patients before treatment, reviews various modalities of treatment, including modern hysteroscopic approaches, and evaluates the appropriate candidates for surgical procedures, their outcomes, and postoperative recommendations. In addition, complications specific to these procedures are reviewed.

EMBRYOLOGY

It is unclear what the exact rate of müllerian abnormalities is in the general population, because no good cross-sectional studies of healthy patients have been performed. It is believed that the incidence is in the range of 1% to 6%, with the reported prevalence ranges from 0.16% to 10%.2 These disorders are associated with various gestational complications, including spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth restriction, abnormal fetal lie, preterm labor, and preterm birth.3 Of note, women with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) appear to have a much higher incidence of anomalies relative to the general population.

Three-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies is proving to be an effective modality for evaluating patients with and without RPL. Using this technique, Salim et al4 noted an anomaly rate of 1.7% in patients without RPL and a rate of 6.9% in those with 3 or more losses. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the wide range of abnormalities that may occur. Because such a wide range of abnormalities does exist, an accurate classification müllerian duct anomaly (MDAs) is all the more crucial to enabling the clinician to select the most appropriate treatment options, while avoiding unnecessary surgical intervention. To address this issue, in 1988 the American Fertility Society (AFS) (now the American Society for Reproductive Medicine) published a classification system to standardize the nomenclature among surgeons.5,6

The developmental pathways involved in MDAs provide some useful etiological insight. The paired müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts are identifiable by week 6 of development, and they arise from coelomic epithelium along the lateral walls of the urogenital ridge.

These solid tissue structures elongate caudally, cross the wolffian (mesonephric) ducts medially, and fuse in the midline to form the primitive uterovaginal canal. By week 10, the caudal end of the fused müllerian ducts connects with the urogenital sinus. Next, internal canalization of the müllerian ducts occurs, resulting in 2 channels divided by a septum. The septum is subsequently resorbed in the caudal to cephalad direction, with complete resorption by week 20. The fused caudal portion of the müllerian ducts becomes the uterus and upper vagina, and the unfused cephalad portion becomes the fallopian tubes.7

The most prominent theory suggests that the müllerian ducts initially fuse together as one structure and that this begins caudally at the müllerian tubercle and proceeds unidirectionally in a cephalad manner. The ultimate result is one cavity that is divided in the midline by a septum, which is then reabsorbed. Given the wide range of abnormalities, early in the century it was suggested that resorption of the septum may begin anywhere within the septum and proceed in either or both directions. Uterine anomalies were thus attributed to either failures of the müllerian elongation process, abnormal fusion, canalization, or resorption. More recently, several case reports of patients with a uterine septum and cervical duplication with a vaginal septum have been published–cases that would be inconsistent with the aforementioned hypothesis.8,9 Muller et al10 proposed an alternate theory suggesting that, at the beginning of the 10th week, the lowermost portions of the müllerian ducts (between the isthmus cranially and the urogenital sinus caudally) fuse at the medial aspects. This creates a single cavity that comprises the upper vagina, cervix, and isthmus. Interestingly, they suggest that at the upper aspects there is not true fusion, but rather at the triangular junction between the 2 müllerian ducts, there is rapid division of cells that then connects the 2 ducts and converges with the lower septum. As with the original hypothesis, it is believed that resorption then follows. As prior case reports suggest, in this model, even if the initial fusion occurred incorrectly if the upper fusion did occur, a patient might have a vaginal septum and 2 cervices, but still have a unified cavity, separated by a septum. Septum can extend into the cervix or even into the entire length of the vagina. The thickness of the septum can also differ, presenting in either thin or thick variations.

Patients with uterine anomalies may also have associated anomalies of the urogenital tract due to their close relationship during embryologic development. In the case of a unicornuate uterus, it has been estimated that up to 40% of patients may have renal anomalies as well. These are generally noted on the side of the remnant uterine horn.11 In an early report, Valle and Sciarra12 found 2 of 12 patients with uterine septum to have a urologic abnormality. More recently, Heinonen,13 in evaluating patients with a complete septum and vaginal septum, found that 11 of 55 patients (20%) had genitourinary abnormalities, 5 of whom had ipsilateral renal agenesis, while 6 had double ureters.

MORPHOLOGY

The actual morphology of the uterine septum has been suggested as the reason for poor reproductive function in patients with this abnormality. The most common hypothesis suggests a decrease in vascularity to the septum that may lower the likelihood of implantation and functional placenta ionization. Several groups have investigated these tenets to ascertain whether differences exist within the structure of the septum versus normal uterine tissue that might lead to reproductive loss. Sparac et al14 performed resectoscopic biopsy of septa in 63 women undergoing metroplasty. They noted preoperatively that evaluation of the uterine septum with transvaginal color Doppler imaging demonstrated vascularity consistent with radial arteries. Histopathology of the septum specimens demonstrated both connective tissue and myometrial tissue. They proposed that the muscular tissue within the septum might create irregular contractile patterns that may increase the risk of abortion. Fedele et al15 evaluated the ultra structural aspects of the uterine septum, as well as endometrium from the nonseptal lateral wall.

Using scanning electron microscopy, they demonstrated the following changes in the tissue overlying the septum: reduced number of glandular ostia, irregular nonciliated cells, and a decrease in the ciliated/nonciliated ratio. They believe these changes represent a decrease in the sensitivity of the endometrial cells overlying the uterine septum, which might have an impact on the receptivity to embryos.

WORKUP

Many individuals will have a uterine septum diagnosed as part of an evaluation for repetitive loss. In these settings, a complete workup and evaluation for the underlying issues of reproductive loss should be performed.

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is one technique used for identifying a uterine/müllerian abnormality. The test is relatively easy to perform, with low associative costs compared with surgery. Uterine subcavities generally are well visualized, and often the extent of the uterine septum may be estimated.16 Unfortunately, frequent overlap occurs in the HSG imaging findings between certain anomalies. For example, the radiographic appearance of the uterine septum is not significantly different from a bicornuate uterus, which is managed in a much different fashion. One study found only 55% accuracy in differentiating these entities via HSG, with the difficulty being that the uterine fundus cannot be evaluated to assess whether an indentation exists.17 In addition, smaller uterine septa may be missed if a significantly anteverted or retroverted uterus is not brought into an axial plane or if a medium is injected too quickly to outline the uterine cavity.

Nevertheless, HSG does provide a few distinct advantages, namely its simplicity of application and its ability to concomitantly evaluate the fallopian tubes. HSG has also been used in postoperative evaluations after septoplasty to determine whether a residual septum is still present. However, this technique is more invasive than other imaging modalities, requiring the insertion of either a canula into the external os or a balloon-tip catheter into the endometrial cavity. More importantly, the external uterine contour cannot be evaluated, which limits the assessment capabilities for müllerian duct anomalies. Moreover, the use of ionizing radiation in a young female patient is an inherent disadvantage. Overall, although HSG plays an integral role in assessing fallopian tube patency in the infertile patient, for the evaluation of MDAs its use provides relatively minimal value, especially in the view of its several significantdisadvantages.6

Yaşar et al18 performed a study of 47 consecutive cases to determine the incision line in the treatment of septate uterus. In all cases, septum incision was performed with a hysteroscopic resectoscope under laparoscopic supervision. Methylene blue 0.25% was injected through a Rubin canula for the assessment of tubal patency. Following the methylene blue injection, a hysteroscopic septum incision was performed by blue line on the top of the cavity, which is observed in 33 of 47 (70.2%) cases. This line (blue line) can be used not only for determining the midline especially before hysteroscopic incision of uterine septum but also for shortening the operation time.

Ultrasonography is the simplest and least invasive methodology for evaluating the uterus, as well as other pelvic structures. More recently, the addition of saline infusion sonohysterography (SHG) has also been used to aid in further evaluating the uterine cavity. Transvaginal ultrasound may be superior to transabdominal ultrasound, although both have been effectively used. As one scans from one cornua to the next, the ultrasound appearance of the septate uterus demonstrates little or no indentation at the fundus. The septum itself appears as a different echogenic area within the endometrium and extending cephalad. Pellerito et al19 noted 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity for diagnosing a uterine septum. Alborzi et al20 performed a small prospective trial and noted the ability of SHG to differentiate a bicornuate from a septate uterus. Given these findings, they questioned whether laparoscopy would be necessary. Most recently, 3-dimensional ultrasound has been suggested as an improved tool for accessing müllerian abnormalities.21 Raga et al22 evaluated 3-dimensional ultrasound and found a 91.6% correlation with laparoscopic findings.

Three-dimensional transvaginal US allows for the creation of 3-dimensional images from a uterine volume acquisition. After the acquisition, the data set can be manipulated to provide 3-dimensional images of the uterus from virtually any angle. This technique allows for the creation of the coronal images, which are essential in the assessment of MDAs, and provides details regarding both the endometrial cavity and serosal surface of the uterus. In experienced hands, a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 100% has been reported in the assessment of MDAs.4Compared with MRI, again in experienced hands,5 important advantages of this technique include its shorter examination time and lower overall costs.

The relatively recent advent of 3-dimensional US has allowed for increasingly accurate evaluation of MDAs, which are best evaluated during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, when the endometrial echo complex is optimally visualized.

Conventional sagittal and transverse images of the uterus, as provided by 2-D technologies, are still important. However, the orthogonal images of the long axis of the uterus, which are crucial for assessing the uterine fundal contour, are significantly enhanced with 3-D imaging. Still, other studies present less compelling evidence concerning the 3-D ultrasound’s ability to add additional information above and beyond that detected with standard 2-dimensional imaging.23

Overall, given the well-documented advantages of SHG, including its high rates of sensitivity and specificity, as well as its relative ease of use, this newer 3-D technology may prove difficult to justify when considering its limited availability, comparatively higher costs compared with SGH, and the paucity of trained sonographers and sonologists with adequate training in 3-D image acquisition and post-processing techniques.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is yet one more imaging modality available for evaluating müllerian abnormalities.8 Several studies have suggested that MRI has a high ability to noninvasively differentiate uterine anomalies, especially in complex anatomic situations.24,25 Fedele et al26 suggest that uterine septa have MRI findings of maximal fundal indentation of ≤10mm and an angle of ≤60° between the medial margins of the hemi cavities. Doyle27 compared ultrasound, HSG, and MRI for diagnosing müllerian abnormalities and noted the correct anatomic diagnosis 96%, 85%, and 6% of the time, respectively. Given the expense of MRI, its use might be most appropriate for situations that are complicated or when multiple anomalies are believed to concomitantly exist.

Septate uteri are classified by whether the septum is complete or partial. A septate uterus is considered complete when the septum extends from the fundus to the external cervical os (Figure 1). The septum can extend even further caudally into the vagina in approximately 25% of cases. In a partial septate uterus, the septum can be of widely variable length. A short septum extends from the fundus and terminates within the body of the uterus (Figure 2), while a longer, incomplete septum may extend beyond the internal cervical os into the endocervical canal, terminating proximal to the external cervical os. In rare instances, the cervix can be duplicated in a septate uterus.6

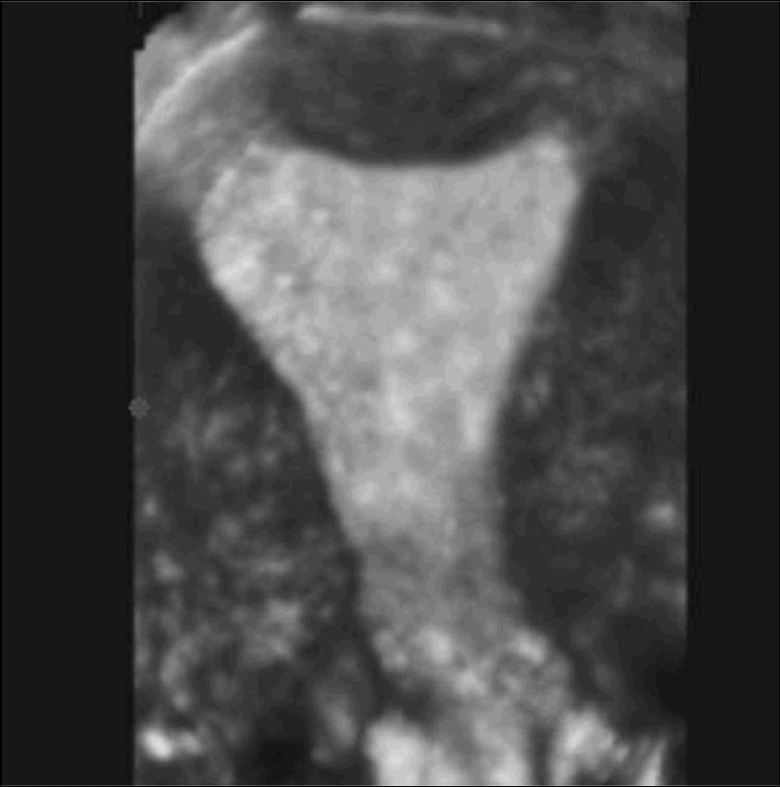

Figure 1. Normal 3-dimentional ultrasound for the uterus. Three-dimentional coronal reconstruction provides an excellent depiction of the endometrium and the external uterine fundal contour.

Figure 1. Normal 3-dimentional ultrasound for the uterus. Three-dimentional coronal reconstruction provides an excellent depiction of the endometrium and the external uterine fundal contour.

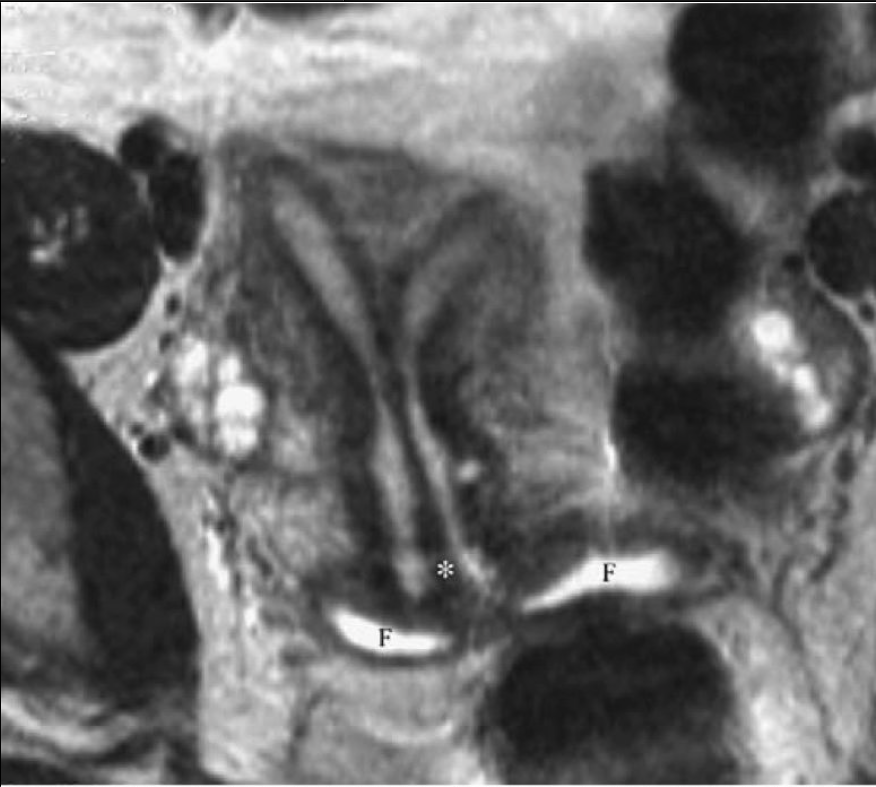

Figure 2. Complete separate uterus. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a prominent midline septum (*) extending from the uterine funds. Cervical os. A small amount of Surgilube is noted within vaginal fornices (F).

Figure 2. Complete separate uterus. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a prominent midline septum (*) extending from the uterine funds. Cervical os. A small amount of Surgilube is noted within vaginal fornices (F).

HSG was historically used for initial imaging assessment of a septate uterus. The size and extent of the septum can be well visualized using this technique (Figure 2). In the past, an intercornual distance of <4cm was a traditional criterion thought to suggest the presence of septate uteri. However, it has proved to be unreliable and is therefore no longer used.

An angle <75° between the uterine horns (intercornual angle) is suggestive of a septate uterus, whereas an angle >105° is suggestive of a bicornuate uterus. However, the intercornual angle often falls between 75° and 105°, leading to considerable overlap between these 2 anomalies when using HSG. The diagnostic accuracy of HSG is limited in the presence of uterine leiomyomata, or any other condition that causes distortion of the myometrium, because the endometrial cavity can be altered, thereby providing misleading results.

Hysteroscopy remains the standard for evaluation of intracavitary abnormalities. Its use is especially practical, as it offers the opportunity for treatment at the time of diagnosis.

Unfortunately, hysteroscopy does not allow evaluation of the external uterine contour, and thus a firm diagnosis of septate versus bicornuate uterus cannot be established simply by hysteroscopy alone. Culdoscopy has also been suggested as an alternative to laparoscopy or other imaging technologies as a means for directly inspecting the uterine contour. Scott and Magos28 reported a case in which ultrasound could not rule out a bicornuate uterus, but with culdoscopy a normal uterine contour was demonstrated and allowed hysteroscopic septoplasty to then be performed in real time. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for evaluation of the uterus and the adnexa and also provides opportunity for concomitant visualization during the operative hysteroscopic procedure.

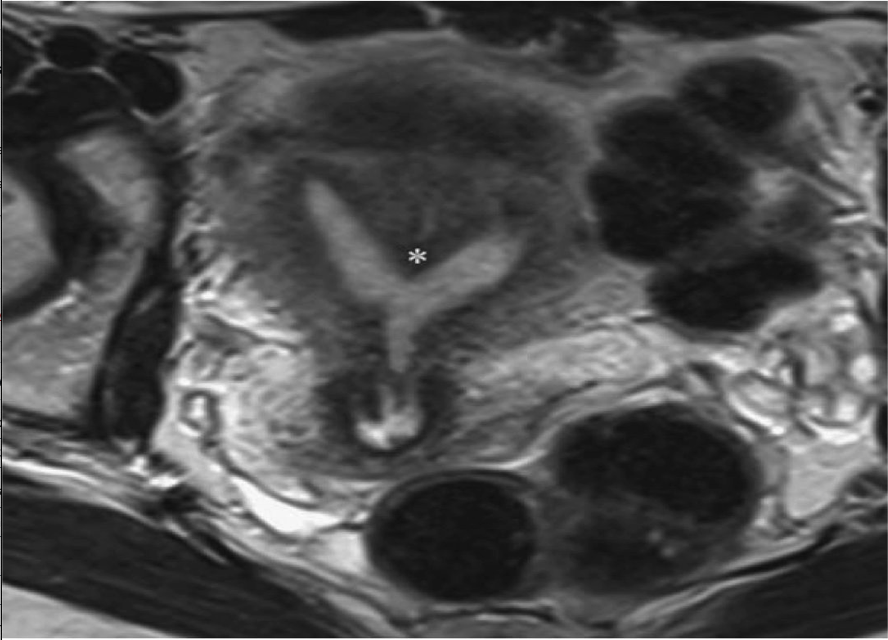

Figure 3. Partial septate uterus. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates prominence of the fundal myometrium with a deep cleft separating 2 fundal endometrial cvaties. A truncated septum (*) terminates within the body of the uterus.

Figure 3. Partial septate uterus. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates prominence of the fundal myometrium with a deep cleft separating 2 fundal endometrial cvaties. A truncated septum (*) terminates within the body of the uterus.

PROCEDURE

Preoperative

Once the workup has been completed and a decision made to proceed with surgery, consideration as to the timing of surgery should occur. Generally, we prefer to perform surgery in the follicular phase as early as possible, after the patient has finished menses. At this point, there is minimal endometrial tissue present to obscure visualization during hysteroscopy, as well as limited vascularity. Cervical cultures may be performed on patients who might be at higher risk, and a pregnancy test should be performed if there is any possibility of pregnancy. Endometriosis has been identified in up to 30% of fertile and infertile women with septate uteri.29

Some have proposed the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or agents, such as danazol, before surgery as an alternative to performing surgery during the follicular phase. Results have been mixed with some of these interventions, especially as they relate to metroplasty. Perino et al30 compared the GnRH agonist leuprolide with no treatment preoperatively in patients undergoing septoplasty and noted no difference in operative time, intraoperative bleeding, or use of media between the groups. In contrast, Fedele et al31 compared GnRH agonist with danazol as pretreatment and noted that use of danazol made the procedure simpler and also allowed easier introduction of the resectoscope. Although we did use these agents earlier in our experience, for simple uterine septum cases we now proceed more expediently to surgical correction, because we prefer that our patients avoid enduring the side effects of agents that appear to provide only negligible net gains. There may be, however, unique situations in which pretreatment might still be considered appropriate.

Figure 4. Separate uterus

Figure 4. Separate uterus

Hysterosalpingography demonstrates 2 divergent uterine horms. A bicornuate uterus cannot be definitively exluded based on this study, because the fundal contour cannot be assessed.6

Surgery

The surgical technique for metroplasty has evolved profoundly since the time when the Tompkins of Jones procedure was standard treatment. Currently, hysteroscopic techniques have supplanted open techniques, unless other pathology dictates a laparotomy. However, even in this setting, hysteroscopic treatment of the uterine septum would still be recommended secondary to the decrease in potential subsequent risk.

Multiple methodologies exist for the actual performance of the surgery, including operative hysteroscopy with scissors, resectoscopic incision, laser metroplasty, and bipolar needle electrodes. Not one of these techniques has been demonstrated to be superior to another. When the use of electrosurgery and laser became more prevalent, there were initial concerns that these modalities could cause lateral thermal damage, thereby decreasing healing or increasing the likelihood of subsequent adhesion formation. Fortunately, the uterus and the endometrium in particular, appear to have a high inherent ability to heal, making these concerns largely unfounded. Advantages associated with the use of scissors (or laser) include the ability to use electrolyte-containing isotonic solutions, such as normal saline or lactated Ringer’s, which can only be applied when electrosurgical interventions are not used. In addition, scissors may often be introduced through a relatively small operative hysteroscope, versus the larger caliber of the resectoscope. More recently, the modified urologic resectoscope has become the most widely used instrument for hysteroscopic metroplasty, with either a pointed (Figure 5) or a 0-degree loop electrode being used.32

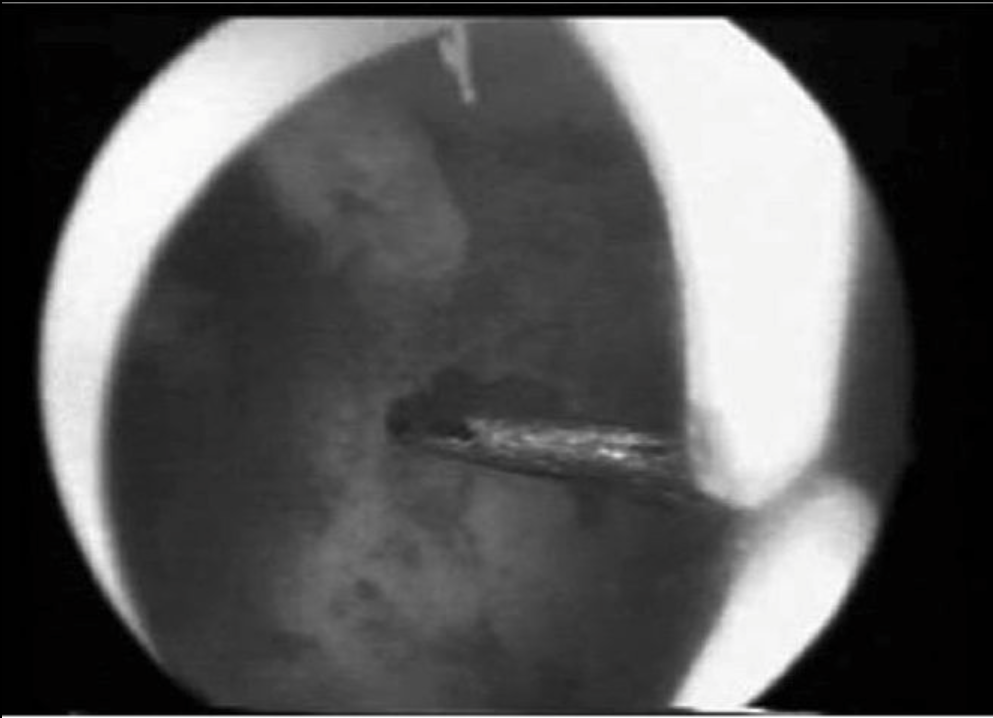

Figure 5. View of the resectoscopic electrical knife tip at the apex of a uterine septum before its incision

Figure 5. View of the resectoscopic electrical knife tip at the apex of a uterine septum before its incision

Alternatively, the 180° loop may be used with the resectoscope. Given its larger diameter, it may facilitate greater disbursement of fluids within the cavity, thus improving visualization.

Inpatient metroplasty carried out with a 5-mm hysteroscope was assessed in a randomized and multicenter trial by Colacurci et al.33 One-hundred and sixty patients with septate uterus were randomly assigned for septum division, either by a bipolar microelectrode or resectoscope with monopolar knife. Operative time, fluid absorption, and complication rates were higher in the resectoscopic arm. No difference in reproductive outcomes between the 2 treatment arms was reported. Similar results were obtained by Litta et al34 in a retrospective controlled trial of 42 patients undergoing inpatient mini-hysteroscopic bipolar metroplasty. An evolution in hysteroscopy practice started with the availability of small-diameter operative hysteroscopes and adaptable mechanical or electrosurgical instruments. Outpatient mechanical polypectomy35 and metroplasty36 have resulted in effective procedures. However, beneficial results have been obtained only in observational and uncontrolled trials. Current data about bipolar electrosurgery in the mini-hysteroscopy approach to endouterine disorders are based on the application of disposable bipolar electrodes. With recent technological improvements in hysteroscopy, the mini-hysteroscopy bipolar surgery now has the potential to replace resectoscopy in most of its applicable fields.37 However, monopolar resectoscopy still represents the current standard in the treatment of endometrial abnormalities, such as uterine septa, myomas, and polyps.38,39 A growing number of studies found hysteroscopy bipolar surgery to be a safe and efficacious alternative. Its safety is indicated by a review of 1822 interventions, among which only one uncomplicated uterine perforation was noted.40 A randomized trial and a retrospective controlled study found that, when used with bipolar systems, small-diameter hysteroscopes, were safer and faster than resectoscopy in the treatment of septate uterus, and reported similar results in reproductive outcomes.18,33 Concerning metroplasty, a retrospective series of 260 patients successfully treated by office mechanical metroplasty was recently reported.36 When subfertility is in the clinical background, it is imperative to treat uterine septum division with the least invasive techniques.41 With this in mind, and in view of these recent findings, we believe that the mini-hysteroscopic approach to metroplasty ought to be considered as the new standard of treatment.

Further, hysteroscopic metroplasty has been demonstrated to significantly improve the live birth and miscarriage rates to approximately 80% and 15%, respectively.1 When the uterine septum is implicated in RPL, or when there is second trimester loss, malpresentation, or preterm delivery, the hysteroscopic approach is preferred due to its safety, simplicity, and excellent post treatment results.41 Concomitant laparoscopy enables evaluation of the pelvis and external uterine contour and guides the extent of septum resection. Traditionally, the cervical portion of a complete septum is left intact due to the risk of cervical incompetence.44,45 53,54 However, a recent small randomized study46found that resection of the cervical septum was associated with a less complicated surgical procedure and equivalent reproductive outcomes.

Postoperative formation of intrauterine synechiae is rare. Therefore, routine use of an intrauterine balloon catheter, estradiol supplementation, or antibiotics has not been shown to be necessary. A follow-up examination should be performed 1month to 2 months after the procedure; ultrasonography, HSG, and hysteroscopy are reasonable approaches.41

Although data suggest it is possible to perform metroplasty without a laparoscopy in patients in whom the diagnosis of a uterine septum is assured, many surgeons still prefer to have a laparoscope in place to guide the procedure. Initially, it must be ascertained whether the patient also has a concomitant vaginal septum. This may be removed in the same setting, allowing easier access to the subcavities.24 Assessment should have already been performed to evaluate whether the patient has 1 or 2 cervices. Diagnostic evaluation may then be performed to evaluate the extent of the septum, thickness of the septum, position of the ostia, and relative size of the 2 subcavities, and whether other concomitant pathologies, such as polyps, leiomyomata, or intrauterine adhesions, exist. Depending on their position within the cavity, it might be necessary to first deal with these issues before beginning the septoplasty. It is particularly important to understand the position of the uterus and, preferably, through the use of a tenaculum, to bring the uterus into a midaxial position. Once the anatomy has been well defined, incision of the septum may be started. Historically, it was believed that the septum would need to be resected. It is now apparent that, in almost all patients, even those with thick septum, removal is rarely required. As the septum is slowly incised, the tissues will retract anteriorly and posteriorly, thus obviating the need for resection or removal. It is crucial to stay in the midsection of the septum as the incision proceeds. It is relatively easy to begin incising ever more posteriorly and eventually into the endo- or myometrium. By making slow progress with the incision and continuously backing away from the septum and reassessing progress, it may be easier to maintain the correct area of incision. As the procedure progresses, it is also critical to continuously monitor the position of the ostia to best appreciate how far cephalad to carry the incision. Some authors have suggested that most uterine septa are relatively avascular, and thus the upper margin of the incision may be reached, until or unless a point of bleeding occurs. Unfortunately, the previously presented data regarding the morphology of uterine septa do not exactly correlate with this clinical picture of minimal bleeding and avascularity. If a laparoscope is in place, this may also help to elucidate the breadth of the incision. Occasional transillumination will demonstrate the relative thickness of the remaining myometrium. Unfortunately, there is no foolproof method for gauging whether the incision has been made far enough or whether a residual septum will result, possibly requiring additional surgery, versus extending the incision too far into the myometrium and increasing the risk of subsequent uterine rupture.

Allowing the intrauterine pressure to decrease will provide the surgeon another means for assessing whether additional incisions are needed and whether there are bleeding points that need to be controlled. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of the procedure is the determination of the end point. This point is achieved when the hysteroscope can be moved freely from one ostium to the other, when the ostia are simultaneously visible from the upper regions of the cavity, and, less importantly, when the uterine fundus seems uniform.

However, dissection should be terminated if significant bleeding is encountered, even when complete transection of the septum has not been achieved, for such an event suggests that the myometrium has been violated.32 This margin of safety is especially crucial to consider, because many studies demonstrate that septal remnants of <1cm may not worsen the reproductive prognosis, although the veracity of this observation has recently been debated.43 It is still preferable to leave a small portion of septum rather than damage the myometrium or perforate the uterus, because any remaining portions of the septum could always be resected with a subsequent procedure if necessary.

In the case of a complete septum, with or without duplicated cervices, it will be more difficult to begin the procedure. In these situations, a Foley catheter bulb may be placed in one of the subcavities and an incision will be required from one subcavity to the other through the septum.44 Although some authors have advocated avoiding incisions to unify cervices, more recent data have suggested this is unnecessary and may increase the duration, as well as difficulty, of the procedures without a substantive change in outcome.42

It is critical during septolysis that fluid input and output be continuously measured. This is true for all cases, but is especially true if using electrosurgery and hypotonic media such as glycine or sorbitol. Although most metroplasty procedures will be of relatively short duration, if a venous sinus is entered, fluid may be lost at a much faster pace.

Intravenous antibiotics may be used during metroplasty, although little good evidence exists to support this practice in patients who have negative cervical cultures. However, as most patients undergoing these procedures are desirous of subsequent fertility, risk of subacute infection may cause many surgeons to administer a broad-spectrum antibiotic during surgery, as well as for a period of time postoperatively.

Bipolar and monopolar resectoscopic loops were compared in one randomized study and showed similar efficacy and safety. Inpatient mini-hysteroscopy by microelectrodes is effective in interventions, usually accomplished by resectoscope. The only randomized trial comparing operative outcomes of monopolar and bipolar loops was reported by Berg et al.45

In this study, 200 patients were randomized to groups undergoing myomectomies or endometrial resections in 3 arms using a monopolar loop (Olympus, 4-mm deep and 5- mm wide) and 2 bipolar loops of different sizes (Olympus, 3-mm deep, 5-mm wide, and Gynaecare, 2-mm deep, 4-mm wide). This is the only randomized study comparing monopolar and bipolar resectoscopic interventions, demonstrating significantly lower serum sodium changes with bipolar devices. The surgical efficacy of larger bipolar loops does not differ with respect to standard monopolar loops. In this study, bipolar metroplasty proved to be safer and more effective than resectoscopes.

Although outpatient operative hysteroscopy is still a developing field, retrospective reports have demonstrated its effectiveness and safety.

Gyneco-radiologic Procedures

Karande and Gleicher46 reported an alternate method of treatment of the uterine septum using fluoroscopic techniques. They reported on 14 patients who underwent incision of their septa with hysteroscopic scissors and a special balloon cannula or microlaparoscopy scissors and a cervical cannula. They were able to successfully complete these procedures in an ambulatory setting. Unfortunately, this is only a small case series and long-term results are not known. The advantage of avoidance of anesthesia and complications of fluid media must be weighed against the exposure to ionizing radiation and the limited experience.

Postoperative Management

Postoperatively, patients may require little, if any, specific treatment. Historically, balloon catheters or occasionally inert intrauterine devices (IUDs) were placed within the uterine cavity in an effort to keep the denuded areas where the septal incision was performed from adhering together. Limited specific data exist to support or refute these practices. Fortunately, in the majority of cases, few adhesions will exist postoperatively and rarely will the walls fuse together.

Estrogen has also been administered after septoplasty in an effort to promote endometrial regrowth into the denuded areas. Typically, in patients who did not otherwise have a contraindication to estrogen, a relatively high dose of daily conjugated estrogen 1.25mg to 5.0mg would be prescribed for 1 month to 2 months, followed by progestin on the last 10 days. More recently, Dabirashrafi et al47 evaluated this practice by performing a randomized prospective trial on 50 patients undergoing septoplasty. At follow-up postoperative examination, no patients in either the estrogen treatment or the no- treatment group were noted to have intrauterine adhesions or septal fusion. Nawroth et al48similarly retrospectively evaluated postoperative treatment via cyclical hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or an IUD, HRT alone, or no treatment. Similar subsequent ongoing pregnancy rates were seen between the groups, and the authors suggest no need for specific postoperative treatment.

After several months, patients may be reevaluated with HSG or hysteroscopy to assess the completeness of septal removal. It has generally been believed that a small residual septum ≤1cm may have only a negligible impact on subsequent reproductive outcomes. Fedele et al49 evaluated this issue, studying the subsequent reproductive history in patients with residual septum between 0.5cm and 1cm in size. In this trial, they noted no difference in outcome between the groups with a normal cavity versus a larger defect.

Kormanyos et al50 evaluated this issue prospectively by studying 94 patients who had 2 or more miscarriages and were undergoing hysteroscopic metroplasty. In 62%, the septum could be removed in its entirety with the initial surgery. Follow-up of the group of patients with normalized cavities versus those with a residual septum demonstrated a significant difference in reproductive loss in the residual group. Given these numbers, it is worthwhile to make patients aware that more than one procedure may be required to completely restore the cavity tonormal.

RESULTS

Multiple studies have retrospectively evaluated the impact of septolysis on reproductive outcome. Unfortunately, no prospective, randomized trials exist to help better define whether a particular group of patients should not be treated. Many of these trials contain a cornucopia of patients, ranging from those with primary infertility to multiple pregnancy losses. One of the largest reported trials evaluated 10 years of an Italian experience.51 They noted that, in the late 1980s, procedures were evenly divided between use of scissors and the resectoscope. Since then, the majority of procedures have been performed resectoscopically. In reporting on pregnancy outcome after metroplasty, they note 78% of patients reached term, 14% had miscarriages at 12 weeks or earlier and 4% had miscarriages after 12 weeks gestation. Of interest, 88 of 808 patients had a postoperative evaluation that demonstrated a fundal notch ≥1cm in size. Valle56 reported on 124 patients with uterine septa (115 of whom had reproductive loss and 9 of whom had infertility) who underwent hysteroscopic treatment. Preoperatively, pregnancy results were poor, with 258 prior miscarriages (86.6%) and 28 preterm births (9.6%). After hysteroscopic treatment, results were markedly improved, with 81% of patients achieving pregnancy; of these, 83% were term, 7% were preterm but viable, and only 12% ended in first-trimester losses. Valle52 also reported favorable results in a small subset of patients who had a septum that continued through the cervix. Homer et al41 reported on an analysis of multiple studies published in the literature and found a miscarriage rate of 88% in 658 patients prior to septoplasty, with a term delivery rate of only 3%. After surgery, this improved to a term delivery rate of 80%, with 14% miscarriages and 6% preterm. These results are typical of the many smaller trials that are reported throughout the literature.53-57

Most recently, Parsanezhad et al42 performed a randomized trial in patients with a complete septum extending to the cervix, comparing incision versus preservation of the cervical septum. They noted that preservation of the cervical septum was associated with longer operating times, greater fluid loss during surgery, and several cases of significant bleeding and pulmonary edema that were not seen in the group that had the cervical septum removed. Additionally, no differences were subsequently seen in reproductive function.

What remains unclear is whether surgery is necessary in a nulligravid patient who is considering pregnancy and has been diagnosed with a uterine septum. Undoubtedly, many such patients are never diagnosed with an abnormality and carry their pregnancies uneventfully. Unfortunately, there again are no good data on how to best manage this scenario. When treatment has required a laparotomy, and even early on in the hysteroscopic experience, many investigators have recommended that patients have at least 3 miscarriages before entertaining treatment. As the technique has evolved, with excellent results and low morbidity, the prior recommendations have decreased to the present time, when some would advocate for the patient mentioned previously to undergo surgery to decrease the potential risk of miscarriage. Contrary to this opinion, investigators in Finland retrospectively evaluated 67 patients with a complete septate uterus and longitudinal vaginal septum.13 In this cohort, only 36 of the patients had their vaginal septum incised, and only 4 underwent metroplasty. Eight of 51 women (15.7%) attempting conception were diagnosed with nonuterine infertility, whereas 49 women who did not undergo metroplasty had 115 pregnancies (live birth, 72%; preterm, 12%; and miscarriages, 27%). In an in vitro fertilization (IVF) unit in Israel, a 29-year-old patient with a complete uterine septum had one embryo placed in each subcavity, with subsequent pregnancies in both.21 Interestingly, at the time of cesarean delivery, metroplasty was attempted, but subsequent evaluation demonstrated a residual septum through 40% of the cavity.

Although there is reasonable agreement that uterine septa increase pregnancy wastage, there remain questions regarding the impact of a septum on fertility itself. Pabuccu and Gomel58 evaluated this issue in a prospective observational study on the impact of hysteroscopic metroplasty in 61 patients with primary unexplained infertility. They reported that after surgery, 41% conceived within 8 months to 14 months, with 29.5% of the group having live births. They concluded that surgery might benefit this cohort of patients.

A further question is the issue of management before assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatments. Dicker et al59 studied 144 women who had elevations in human chorionic gonadotropin-beta (hCG-b) after treatment, but no other clinical evidence of pregnancy, in other words, what appeared to have been instances of preclinical spontaneous abortions. Hysteroscopy demonstrated that 14 of 144 of these patients (9.7%) had at least small uterine septa. Lavergne et al60 evaluated the pregnancy rates in patients undergoing ART treatments who were confirmed to have congenital uterine anomalies. Compared with a control group with a normal uterus, the pregnancy rate per embryo transfer for this group was decreased from 24.9% to 13.6%, while the implantation rate decreased from 11.7% to 5.8%. They note that implantation rates increased when the underlying anomaly could be surgically treated. These data might support intervention before attempted ART in this higher-risk group.

Concomitant laparoscopy enables evaluation of the pelvis and external uterine contour and guides the extent of septum resection. Traditionally, the cervical portion of a complete septum is left intact, due to the risk of cervical incompetence. However, a recent small randomized study demonstrated that resection of the cervical septum is associated with a less complicated surgical procedure and equivalent reproductive outcomes.25,42

Prophylactic hysteroscopic metroplasty in infertile women or women without a history of adverse reproductive outcomes is a controversial procedure because many women with a septate uterus can have reasonable pregnancy outcomes, and there is no established causal relationship between a septate uterus and infertility.61-62 After hysteroscopic metroplasty in women with unexplained infertility, a modest improvement in pregnancy and live birth rates is demonstrated in nonrandomized trials. These rates are significantly higher after metroplasty in women with RPL, which highlights the difference in fertility between these 2 populations.58

Many of these women can have normal reproductive outcomes, but intervention is recommended in the event of poor obstetric outcomes. Moreover, due to the ease and low morbidity associated with hysteroscopic metroplasty for a septate uterus and demonstrated improvement in obstetric outcomes, this procedure should be considered in infertile women with a septate uterus prior to advanced fertility treatment.7

A retrospective comparative study in 31 women who had a term pregnancy from January 1996 through December 2004 after hysteroscopic metroplasty for septate uterus (group A) were studied. A control group (group B) of 62 women who had term pregnancies but no history of hysteroscopic metroplasty was selected from the same database. Obstetric complications at term and neonatal outcomes after hysteroscopic metroplasty were compared between these 2 groups. The results of this study suggest that patients with a previous hysteroscopic metroplasty for septate uterus are at increased risk for fetal malpresentation at term, low birth weight infants, and caesarean delivery. Therefore, these patients should be informed of these risks before delivery.63

Complications

Complications for hysteroscopic metroplasty include not only the general complications of hysteroscopy, as previously detailed throughout the text, but also those associated with fluid media and traumatic and hemorrhagic complications. Kazer et al64 reported on 2 cases involving the uncommon complication of late hemorrhage after metroplasty. In one of the larger series to be published on operative hysteroscopic complications Propst et al65 noted a complication rate of 9.5% for uterine septum resection. Unfortunately, there were only 21 metroplasties in this case series, 2 of which involved complications.

One recognized complication of septoplasty is subsequent rupture. It is felt that the general risk of this complication is low given that the active myometrium is likely minimally disrupted. For this reason, cesarean delivery is not usually recommended unless an obstetric indication exists. However, there are now several case reports of uterine rupture after prior hysteroscopic resection. Interestingly, they include cases in which no electrosurgery was used and no evidence of uterine perforation was found at the time of surgery. Conturso et al66 reported on a patient who had undergone a hysteroscopic resection of a septum that was complicated by fundal perforation. In the subsequent pregnancy, at 28 weeks, the patient was noted to have a uterine rupture with protrusion of the amniotic sac. In another report, Angell67 described a patient who underwent an uncomplicated hysteroscopic metroplasty with scissors. Subsequent evaluation demonstrated a residual septum, suggesting that the procedure did not involve active entry into the myometrium. Nevertheless, during the patient’s subsequent pregnancy, a perforation of the fundus from cornua to cornua was noted, causing exteriorization of the fetus and placenta. Given these reports, it is advisable to monitor patients who have undergone prior uterine surgery with a heightened sense of concern during labor. Should there be abnormalities in fetal heart patterns or maternal abdominal pelvic pain, consideration should be given to the possibility of uterine rupture, with appropriate intervention if necessary.

The potential risk of a uterine septum must also be considered in cases of intrauterine contraception. If the diagnosis has not been previously made, an IUD may be placed into one subcavity. Dikensoy et al68 reported on a pregnant patient in whom the IUD was readily visible in the one subcavity, while the pregnancy was visible in the other.

CONCLUSION

The management of the uterine septum has changed dramatically in the last quarter- century, with patients definitely benefiting from the evolution of minimally invasive techniques. In spite of these advances, many questions remain regarding which patient should undergo treatment and at what point. Recent case reports have demonstrated that prior embryogenesis hypotheses may have questionable applicability, a change that requires a continued, reevaluation of these older theories. Given the wide variety of manifestations that may be seen with urogenital anomalies, the astute clinician will need to continually readdress his or her thinking on these relatively common entities.

Overall, due to the ease and low morbidity associated with hysteroscopic metroplasty for a septate uterus, as well as its demonstrated association with improved obstetric outcomes, this procedure should be considered in infertile women with a septate uterus prior to advanced fertility treatment. Diagnosis and classification of müllerian anomalies are facilitated by the availability of excellent imaging techniques; hence, current data on reproductive outcomes with uterine anomalies should be assessed.7

References

- Troiano RN. Magnetic resonance imaging of mullerian duct anomalies of the uterus. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;14:269-279.

- Troiano RN, McCarthy SM. Mullerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical Radiology. 2004;233:19-34.

- Deutch RD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies: a review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:4113-423.

- Salim R, Regan L, Woelfer B, Backos M, Jurkovic D. A comparative study of the morphology of congenital uterine anomalies in women with and without a history of recurrent first trimester miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:62-166.

- The American Fertility Society. Classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49;944-955.

- Olpin JD, Heilbrun M. Imaging of müllerian duct anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(1):40-56.

- Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with müllerian anomalies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(3):229-237.

- Hundley AF, Fielding IR, Hoyte L. Double cervix and vagina with septate uterus: an uncommon mullerian malformation. Obstet Gynecol. 200l;98:982-985.

- Chang AS, Siegel CL, Moiey KH, Ratts VS, Odem RR. Septate uterus with cervical duplication and longitudinal vaginal septum: a report of five new cases. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1133-1136.

- Muller P, Musset R, Netter A, Solal R, Vinourd IC, Gillet JY. State of the upper urinary tract in patients with uterine malformations. Study of 133 cases. Press Medical. 1967;75(26):1331-1336.

- Fedeie L, Bianchi S, Agnoli B, Tozzi’ L, Vignali M. Urinary tract anomalies associated with unicornuate uterus. Urology. 1996;155:847-848.

- Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Hysteroscopic treatment of the septate uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:253-257.

- Heinonen PK. Complete septate uterus with longitudinal vaginal septum. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:700-705.

- Sparac V, Kupesic S, Ilijas M, Zodan T, Kurjak A. Histologic architecture and vascularization of hysteroscopically excised intrauterine septa. J Am Assoc Gyneco Laparosc. 2001;8:111-116.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Marchini M, Franchi D, Tozzi L, Dorta M. Ultrastructural aspects of endometrium in infertile women with septate uterus. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:570-572.

- Proctor JA, Haney AF. Recurrent first trimester pregnancy loss is associated with uterine septum but not with bicornuate uterus. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1212-1215.

- Reuter KL, Daly DC, Cohen SM. Septate versus bicornuate uteri: errors in imaging diagnosis. Radiology. 1989;172:749-752.

- Yaşar L, Sönmez AS, Savan K, Ekin M, Özdemir A, Güngördük K. A practical guide to determine the incision line in the treatment of septate uterus: “Süha Levent’s Sign.” Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(6):809-811. Epub 2008 Oct 21.

- Pellerito JS, McCarthy SM, Doyle MB, Glickman MG, DeCherney AH. Diagnosis of uterine anomalies relative accuracy of MR imaging, endovaginal sonography, and hysterosalpingography. Radiology. 1992;183:795-800.

- Alborzi S, Dehbashi S, Parsanezha E. Differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus by sonohysterography eliminates the need for laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:176-17B.

- Weissman A, Eldar I, Malinger G, Sadan O, Glezerman M, Levran D. Successful twin pregnancy in a patient with complete uterine septum corrected during cesarean section. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):494.e11-4.

- Raga F, Bonilla-Musoles F, Blanes J, Osborne NG. Congenital müllerian anomalies: diagnostic accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasound. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(3):523-528.

- Ayida G, Harris P, Kennedy S, Seif M, Barlow D, Chamberlain P. Hysterosalpingo- contrast to neography (HyCoSy) using Echovist-200 in the outpatient investigation of infertility patients. Br Radiol. 1996:69:9l0-913.

- Carrington BM, Hricak H, Nuruddin RN, Secaf E, Laros RK Jr, H ill EC. Mullerian duct anomalies: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 1990;176:715-720.

- Patton PE, Novy MJ, Lee DM, Hickok LR. The diagnosis and reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal septum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1669-1675.

- Fedele L, Dorta M, Brioschi D, Massari C, Candiani GB. Magnetic resonance evaluation of double uteri. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:844-847.

- Doyle MB, Magnetic resonance imaging in müllerian fusion defects. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:33-38.

- Scott P, Magos A. Culdoscopy to examine the contour of the uterus before hysteroscopic metropolasty for uterine septum. BJOG. 2002;109:591-510.

- Nawroth F, Rahimi G, Nawroth C, et al. Is there an association between septate uterus and endometriosis? Hum Reprod. 2006;21:542-544.

- Perino A, Chianchiano N, Petronio M, Cittadini E. Role of leuprolide acetate depot in hysteroscopic surgery: a controlled study. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:507-510.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Gruft L, Bigatti G, Busacca M. Danazol versus a gonadotropin- releasing hormone agonist as preoperative preparation for hysteroscopic metroplasty. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:186-188.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G. Septums and synechiae: approaches to surgical correction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(4):767-788.

- Colacurci N, De Franciscis P, Mollo P, et al. Small-diameter hysteroscopy with Versapoint versus resectoscopy with a unipolar knife for the treatment of septate uterus: a prospective randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:622-627.

- Litta P, Spiller E, Saccardi C, et al. Resectoscope or Versapoint for hysteroscopic metroplasty. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;101:39-42.

- Garuti G, Centinaio G, Luerti M. Outpatient hysteroscopic polypectomy in postmenopausal women: a comparison between mechanical and electrosurgical J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:595-600.

- Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Nappi L, et al. Office hysteroscopic metroplasty: three “diagnostic criteria” to differentiate between septate and bicornute uteri. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:324-328.

- Garuti G, Luerti M. Hysteroscopic bipolar surgery: a valuable progress or a technique under investigation? Curr Op Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:329–334.

- Sardo AD, Mazzon I, Bramante S, et al. Hysteroscopic myomectomy: a comprehensive review of surgical techniques. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:101–119.

- Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systemic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

- Lindheim SR, Kavic S, Shulman SV, Sauer MV. Operative hysteroscopy in the office setting. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:65-69.

- Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID. The septate uterus: a review of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1-14.

- Parsanezhad ME, Alborzi S, Zarei A, et al. Hysteroscopic metroplasty of the complete uterine septum, duplicate cervix, and vaginal septum. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1473-1477.

- Kormanyos Z, Molnar BG, Pal A. Removal of a residual portion of a uterine septum in women of advanced reproductive age: obstetric outcome. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1047- 1051.

- Rock JA, Roberts CP, Hesla JS. Hysteroscopic metroplasty of the Class Va uterus with preservation of the cervical septum. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:942-945.

- Berg A, Sandvik L, Langebrekke A, Istre O. A randomized trial comparing monopolar electrodes using glycine 1.5% with two different types of bipolar electrodes (TCRis, Versapoint) using saline in hysteroscopic surgery. Fertil Steril. 2009; 91:1273- 1278.

- Karande VC, Gleicher N. Resection of uterine septum using gynaecoradiological techniques. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1226-1229.

- Dabirashrafi H, Mohammad K, Moghadami-Tabrizi N, Zandinejad K, Moghadami- Tabrizi M. Is estrogen necessary after hysteroscopic incision of the uterine septum? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:623-625.

- Nawroth F, Schmidt T, Freise C, Foth D, Tomer T. Is it possible to recommend an “optimal” postoperative management after hysteroscopic metroplasty? A retrospective study of 52 infertile patients showing a septate uterus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:55-57.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Marchini M, Mezzopane R, Di Nola G, Tozzi Residual uterine septum of less than 1 cm after hysteroscopic metroplasty does not impair reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod. 1996:11:727-729.

- Kormanyos Z, Molnar BG, Pal A. Removal of a residual portion of a uterine septum in women of advanced reproductive age: obstetric outcome. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1047- 1051.

- Colacurci N, DePlacido G, Perino Am Mencaglia L, Gubbini G. Hysteroscopic metroplasty. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5:171-174.

- Valle RF. Hysteroscopic treatment of partial and complete uterine septum. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1996;41:310-315.

- Saygili-Yildiz S, Erman-Akar M, Akyuz G, Yilmaz Z. Reproductive outcome of septate uterus after hysteroscopic metroplasty. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-292.

- Valli E, Vaquero E, Lazzarin N, Caserta D, Marconi D, Zupi E. Hysteroscopic metroplasty impro0ves gestational outcome in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:240-244.

- Venturoli S, Colombo FM, Vianello F, Seracchioli R, Possati G, Paradisi R. A study of hysteroscopic metroplasty in 141 women with septate uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;266:157-159.

- Grimbizis G, Camus M, Clasen K, Tournaye H, De Munck L, Devroey P. Hysteroscopic septum resection in patients with recurrent abortions or infertility. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1188-1193.

- Litta P, Pozzan C, Merlin F, et al. Hysteroscopic metroplasty under laparoscopic guidance in infertile women with septate uteri: follow-up of reproductive outcome. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:274-278.

- Pabuccu R, Gomel V. Reproductive outcome after hysteroscopic metroplasty in women with septate uterus and otherwise unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1675-1678.

- Dicker D, Ashkenazi J, Dekel A, et al. The value of hysteroscopic evaluation in patients with preclinical in-vitro fertilization abortions. Human Reprod. 1996;11:730- 731.

- Lavergne N, Aristizabal J, Zarka V, Erny R, Hedon B. Uterine anomalies and in vitro fertilization: what are the results? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;68:29- 34.

- Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G. Septums and synechiae: approaches to surgical correction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:767-788.

- Heinonen PK. Complete septate uterus with longitudinal vaginal septum. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:700-705.

- Aqostini A, De Guibert F. Adverse obstetric outcomes at term after hysteroscopic metroplasty. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:454-457.

- Kazer RR, Meyer K, Valle RF. Late Hemorrhage after transcervical division of a uterine septum: a report of two cases. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:930-932.

- Propst AM, Oberman RF, Harlow BL, Ginsburg ES. Complications of hysteroscopic surgery: predicting patients at risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:517-520.

- Conturso R, Redaelli L, Pasini A, Tenore A. Spontaneous uterine rupture with amniotic sac protrusions at 28 weeks subsequent to previous hysteroscopic Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;107:98-100.

- Angell NF, Tan Domingo J, Siddiqi N. Uterine Rupture at term after uncomplicated hysteroscopic metroplasty. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1098-1099.

- Dikensoy E, Kutlar I, Gocmen A, Graves CR. Two cases of uterine septum with intrauterine device. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:952-943.