Laparoscopic Colon Surgery

Morris E. Franklin Jr, MD, Guillermo Portillo, MD, Karla Russek, MD

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic colon surgery has been performed for a number of years and is widely accepted in the medical community as an alternative for procedures involving benign disease.

For malignant disease, recent studies have shown equal or better oncologic results, favoring the laparoscopic approach, especially when postoperative morbidity is analyzed and careful long-term follow-up is considered.1,2,3

Since early experiences, several intraoperative and postoperative complications have become evident as well as methods and precautions to prevent these often disastrous problems.4,5

PREPARATION

This is an important issue for a successful result in any type of laparoscopic procedure and especially in colon resection.6 A thorough history and physical examination with special emphasis on cardiac and pulmonary problems as well as previous surgeries is mandatory. It is important to perform a complete evaluation of the entire colon, to allow localization of the tumor by means of tattooing or a barium enema and to identify metachronous lesions and disease processes. CT scan and ultrasonography are performed at the discretion of the attending surgeon but are strongly recommended for complete evaluation of not only the colon but also other organs, such as gallbladder and liver lesions. A baseline chemical profile including complete blood count, Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA), preoperative electrocardiogram, and chest X-ray are performed as needed. Pulmonary function tests for patients with compromised respiratory function and additional tests for specific patient’s problems should be appropriately utilized.7,8

The bowel preparation must be modified from those that have been used in past years, because the PEG-3350 and electrolytes for oral solution frequently give inadequate preparation and leave increased fluid in the small bowel. The authors recommend the following guidelines: 5 days prior to the surgery a low-fiber diet should be started; 3 days prior, a full liquid diet, and 2 days before, clear liquids adding 4 tablespoon of milk of magnesia at the middle of the day and another 4 tablespoons 6 hours later. Magnesium citrate (120cc PO q 12hr) and saline enema 8 hours before surgery may be helpful in patients with sluggish colonic activity. Preoperative antibiotics are given at the discretion of the surgeon.7

EQUIPMENT

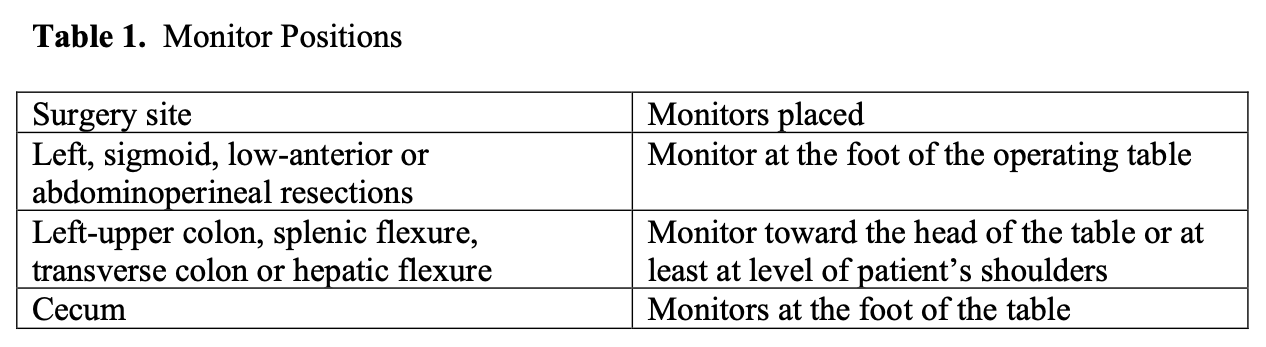

Equipment required for laparoscopic surgery starts with the same basic equipment as that required for laparoscopic cholecystectomy or any advanced laparoscopic procedure. Two monitors placed in accordance with the portion of the colon on which the operation is planned have been found to be extremely helpful (Table 1).

Table 1. Monitor positions.

Table 1. Monitor positions.

A general rule is to “use as many trocars as needed,” and generally a half circle around the target organ is the best setup for trocar placement.9 Standard graspers and special instruments include long bowel-grasping instruments; 5-mm laparoscopic scissors with cautery attachment, and bipolar instrumentation. Cautery capability is needed, as are newer instruments for vessel control, such as LigaSure or LigaSure Advance coagulator device (Valleylab, Boulder, CO) and Ethicon Endosurgery Enseal. Suction and irrigation devices (5mm and 10mm) with extralong wands should be available for use as needed.

Endo-GIA linear staplers with multiple reloads and circular intraluminal staplers of at least 28mm in diameter may also be used as needed. Clips may control smaller blood vessels; however, the authors prefer the use of the LigaSure device. Nonetheless, extracorporeal and intracorporeal knotting skills are generally considered a prerequisite for a successful laparoscopic colon surgery. The availability to perform a colonoscopy will aid in completing the procedure by identifying resection margins and testing the anastomosis. An ultrasound device enhances evaluation of the liver and para-aortic nodes and should perhaps be available in every case. Should circumstances arise that could mandate an open procedure, an instrument table for opening of the patient also needs to be immediately available.7

While a few reports are reinforcing on the use of single-incision techniques for simple laparoscopic colon procedures, the complexity of these procedures and an increasing number of complications arising with this technique result in an increased number of incisional hernias, violation of commonly accepted surgical principles, creation of unusual and dangerous electrical fields, lack of adequate visualization, and no discernible or demonstrated benefit to the patient.10

Since a gynecologist’s survey over 20 years ago, the cause of injury during laparoscopy has been attributed to trauma or electrical injury. Thompson and Wheeless reported 10 electrically induced bowel burns in a series of 3600 cases. All of the above make these procedures experimental at best and should be most likely reserved for experts in the field.11

ANATOMY

Most surgeons are familiar with the anatomy involved with virtually every type of colon resection performed. However, there is a different view of the anatomy with laparoscopy, and although the anatomy does not change, the view through which the anatomy is seen does.10 Several critical areas should be discussed in regard to anatomy, particularly important is the location of the ureters. It is the authors’ contention that the ureter should be identified very early in every colon surgery involving sigmoid, low anterior, and abdomino-perineal resections. The ureter should be used as a reference point whenever there is a doubt as to the anatomy during the course of the dissection. Avoidance of ureteral injuries is imperative, and nonidentification of the ureters is a clear indication to open as far as we are concerned. The duodenum should be clearly identified early in the dissection for transverse colon resection, right and total colectomies, and can be either accomplished as the colon is reflected inferiorly or through a mesenteric window of the hepatic flexure. The spleen should be readily recognized, particularly with left colon resections, where the splenic flexure is mobilized. The middle hemorrhoidal vessels are frequently more clearly seen with laparoscopic surgery than with traditional open surgery and can be confused with the ureters.

The key in recognizing the anatomy is to back up the camera if one gets lost or if the camera is too close, identifying the anatomy that is clearly evident, and then work back from that point to the area in question. Failure of this principle could lead to unnecessary lesions to other organs or misidentification of easily recognizable anatomy.

PATIENT POSITIONING

Correct patient positioning can greatly enhance the performance of any laparoscopic procedure. A modified lithotomy position provides ready anal access with the legs slightly flexed13; Lloyd-Davis or Allen stirrups and the buttocks near the edge of the table are recommended. The rectum can be elevated by placing the sacrum on a Gel foam pad or slightly tilting the rectum forward. Taping the shoulders of the patient without restricting pulmonary function is a method of stabilizing the patient for the air-planning positional changes, and steep Trendelenburg positioning that may be needed for sigmoid and rectal resections; however, beanbags are also effective. Shoulder stubs or pads should be avoided as a sole means of preventing slippage, because this can result in brachial plexus injury. It is also important to protect all exposed nerve surfaces, particularly those around the elbows and knees. The arms need to be secured by the patient’s side to allow maximum tilt and mobility of the surgical team, because arms spread in the classic position may be an obstruction to movement around the operation table. Sequential compression devices are placed on the patient’s legs to help avoid venous stasis and an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis. A warming blanket should be available to help prevent cooling of the patient, which may occur in prolonged procedures.

Provisions should be made for warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids, and the routine use of heparin (7500 UI/Lt) in the irrigation fluid may be helpful in preventing large clots from forming as well as aid in reducing tumor cell adhesion to instruments and trocars.14 With resections for cancer, povidone-iodine as an anticarcinogenic irrigation has been recommended to help reduce tumor cells and prevent tumor cell implantation on trocars andincisions.

Wrapping the lower extremities in plastic is also recommended and may prevent at least 1° of temperature loss per hour in a 2-hour or longer procedure. A Foley catheter and a nasogastric tube should be inserted as needed.

The surgeon’s position is recommended contralateral to the resection site with the camera holder on the same side; additional assistants may be placed between the legs for upper abdominal procedures or on the ipsilateral side for the right, sigmoid, and rectal procedures.

It is very important to emphasize that before embarking upon laparoscopic colon resection, proper expertise with intracorporeal suturing, intraextracorporeal knot-tying, good use of both hands, and experience with stapling devices is essential to avoid unneeded conversions to open procedures. The surgeon and surgical team should be thoroughly familiar with advanced laparoscopic techniques and have attended and practiced advanced laparoscopic colon resection techniques. Time with a surgeon who has been performing colorectal procedures beyond the novice stage is a good investment for the successful outcomes of these procedures.

TROCAR PLACEMENT

The trocars need to be placed strategically to allow good mobilization of the colon and creation of the anastomosis, the colostomy, or both the anastomosis and the colostomy. We preferably use smooth trocars and avoid the screw-in type. They are secured to the abdominal wall to prevent dislodgement and the so-called “chimney effect” whereby possibly aerosolized viable tumor cells could pass through the naked skin edges and become adherent to soft tissue, thus theoretically increasing the risk for port-site metastases. This also prevents inadvertent loosening and extraction of the trocar with consequent loss of pneumoperitoneum and increased CO2 absorption. We generally use a 12-mm trocar strategically placed for colon resections, two 5-mm trocars for the surgeon, and two 5-mm trocars for the assistant. The camera is placed at the umbilicus and is generally a 5-mm trocar.

After insufflation with a Veress needle and placement of the initial trocar in a nonmidline position, a 5-mm scope is introduced and the remaining trocars are placed under direct vision. After these are placed, we initially evaluate the abdominal cavity, looking for prominent lymph nodes, implantation of tumor cells in the omentum, and visualization of the colon, especially in the splenic flexure to ascertain the difficulty of its mobilization, should it be required. The liver is thoroughly examined, and use of laparoscopic ultrasonography can accurately show the presence of metastatic disease to the liver. This may indeed modify the extent of the dissection for a given patient.

The manipulation of the tumor is avoided by gasping the entire circumference of the bowel, with specific bowel handling instruments (eg, Laparoscopic Glassman clamps, and others). Sharp instruments for handling bowel or mesentery are to be avoided if possible.

It is preferable to hold the mesentery or appendices epiploica rather than the bowel itself if specific bowel instruments are not available. The use of smaller instruments frequently results in laceration of the bowel and can convert a clean controlled case into a contaminated surgery.

MOBILIZATION

Frequent use of the Trendelenburg position, often severe, reverse Trendelenburg, left and right tilt, can allow visualization and mobilization of almost any segment of the colon with much less effort than without the help of gravity. The operating table must allow left and right tilt as well as a steep Trendelenburg position. When grasping fat and the colon itself, we recommend the use of blunt instruments, such as Glassman clamps and blunt Babcocks, in colon mobilization. The scissors need to be sharp and possess electrocautery capability.

The authors also prefer to push the colon and other organs out of the way rather than pull them, because pulling, particularly with torquing, tends to injure the colon and other organs. It is necessary to meticulously avoid grasping the bowel that is not to be resected and very carefully avoid grasping the tumor in cancer cases. Blunt dissection is always better than sharp dissection, unless one can actually see through the tissue being dissected.

If there is any doubt as to tissue or anatomy, change the lens or the position of the lens until you can clearly delineate what is being dissected.

It is very important to use gravity as an advantage rather than a disadvantage during mobilization of the colon.

ANASTOMOSIS

Laparoscopic anastomoses can be constructed with either an intracorporeal or extracorporeal technique. The decision on what type of anastomosis to perform depends mostly on the surgeon’s expertise. It has been proven that intracorporeal anastomoses result in shorter incision length and may decrease wound-related complications, but the type of anastomosis does not influence short-term outcomes.15

The basic principles to ensure a viable anastomosis are the same, regardless of the type of procedure.16 Handling of the colon should always be in a gentle way. One should try to avoid direct grabbing of the bowel, and, whenever possible, grab an appendix epiploica to mobilize the specimen, as mentioned earlier in this chapter.

After performing the anastomosis, it is of uttermost importance to be sure of the colon alignment. One should revise the anastomosis site to ensure that the distal and proximal taenias are aligned. An adequate blood supply should always be ensured at the anastomosis site.13

We strongly recommend the use of intraoperative colonoscopy to see the anastomosis from the inside of the colon and ensure there are no bleeding spots. In cases of malignant disease, we irrigate the colon with a dilute Betadine solution. After placing 2 Bulldog laparoscopic clips and irrigating the area, we insufflate the colon and perform an air-leak test.7,17

Suture line reinforcement was introduced a few years back and has been proven to lower the anastomosis leak rate, as well as bleeding and postoperative stenosis, so it should be considered when an anastomosis is being creating.18

The use of a diverting stoma for anastomosis protection has been a controversial subject. We strongly believe there are specific cases where a stoma is needed, for example, whenever an anastomosis is created <5cm from the anal margin, in patients with risk factors that result in a diminished immunological response, cases where the procedure itself was cruent and the leak risk is high. We favor the use of loop ileostomies whenever possible.19

SPECIMEN HANDLING AND REMOVAL

Oncologic principles should always be respected when laparoscopic colon surgery is performed.20,21 This includes specimen handling and removal. After the distal resection of the specimen, we recommend the use of endoloops to prevent the spillage of the colon contents and possible neoplastic implants throughout the abdominal cavity. After the complete isolation of the specimen, we use a bag for its removal. Premade commercial bags are available, but we usually use our own plastic bag that comes with a purse string for easier handling.

The extraction site varies depending on the diagnosis, size of tumor, and patient characteristics.22 Whenever possible, we try to use a natural orifice site for extraction: anal extraction for left colectomies and transvaginal extraction for right colectomies. It has been proven that the use of natural orifices lowers wound-site complications like infection and postincisional hernias.4

In cases of transanal extraction for benign disease, trimming of the mesentery is possible in order to prevent posterior anal sphincter malfunction.

Whenever a natural orifice is not suitable for extraction, we perform a 5-cm incision as an extraction site, always using wound protection.

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

In all our patients, the postoperative medications are the standard agents used in colon resections. The IV fluid administration is based on the patient’s requirements to maintain a urine output of 1mL/kg/hr.

The decision to place a nasogastric tube is made intraoperatively, depending on the manipulation of the bowel, length of surgery (risk for prolonged ileus), and age of the patient. The patient is given IV antibiotics for 24 hours. We prefer cefotaxime, metronidazole, or cefepime, which are known to cover colon flora.

Additional medications include analgesia in restriction but enough to maintain good pain control and medication for the undesirable postoperative nausea. Obviously, other previous medical conditions need to be treated, and medications, such as antihypertensives, diabetic medications, cardiac medications, and others, don’t need to be suspended.

We recommend waiting at least 6 hours to start a diet, but in aging patients the waiting time recommended is 12 hours; however, most patients will tolerate clear liquids the next day. The indication for a full diet should be after the patient has begun to have bowel movements and passage of gas.

The patient’s progress determines the disposition of the patient; the requisites for a satisfactory discharge are for the patient to be able to tolerate a diet, have regular bowel movements, medical problems need to be under control, no fever registered at least for 24 hours. The patient needs to have tolerated ambulation whenever possible, pain is under control, and the wounds are clean and healing. All drains should also be removed. This period of time averages 3.5 days in patients <50 years and 5.5 days in patients >50 years for most colon surgeries.

The timing to return to normal activity is a gray area and is very loosely determined depending on the individual practitioner.23 Most of the patients are able to return to normal activity within 14 days. We do not recommend returning to work any sooner than 5 days to 10 days after surgery, unless the patient has a sedentary occupation. Most patients tolerate the return to full activity, work, or both, within 7 days to 10 days. Some patients who have particular problems may not be able to return to work sooner than 2 weeks. Patients with very heavy labor-related occupations require at least 10 days to 2 weeks before they can return to full, unrestricted work activities.

It is very important to advise patients about fecal urgency and frequency. To help diminish this, we recommend the use of bulky or high-fiber supplements.

COMPLICATIONS

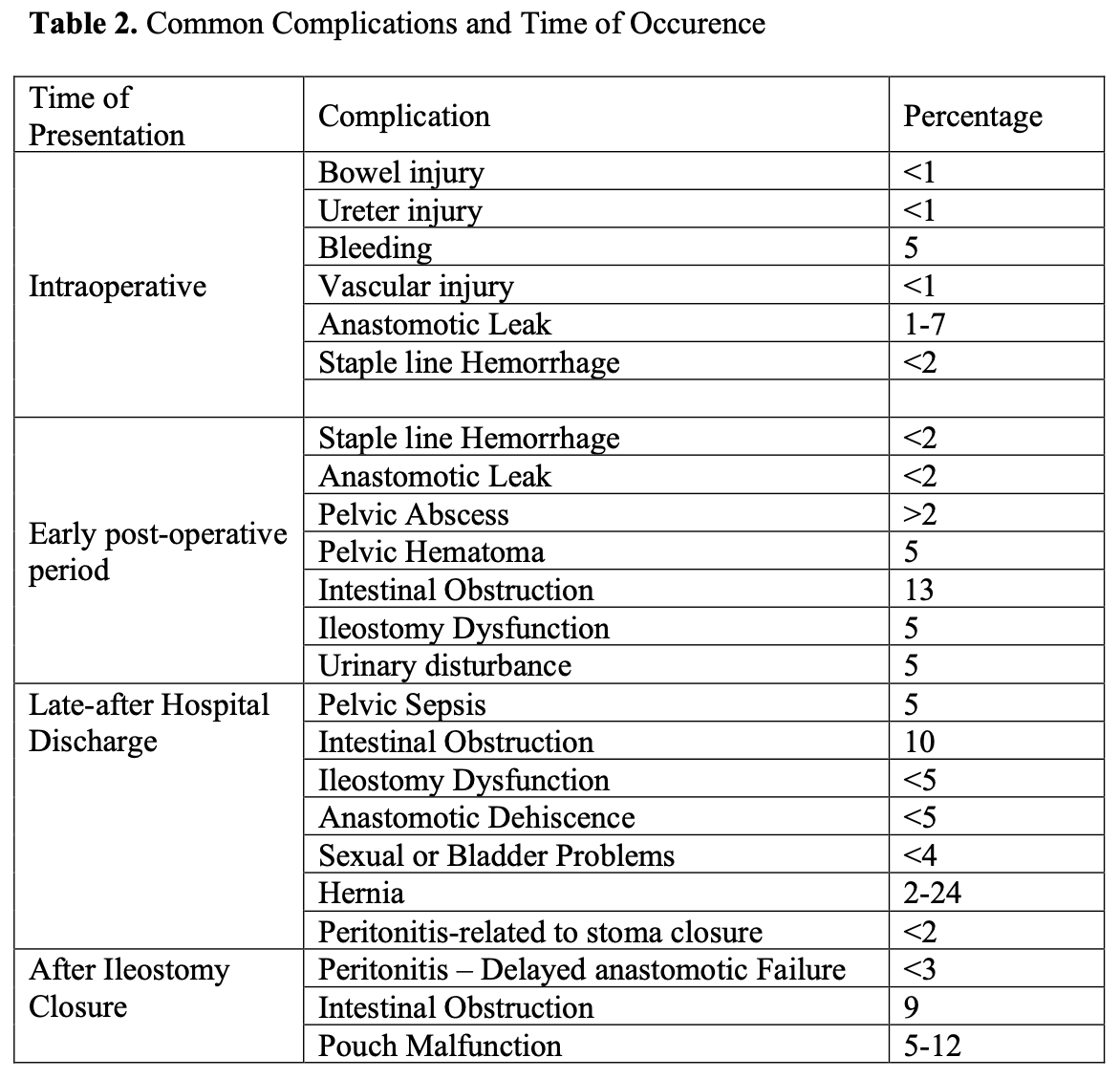

The postoperative complications associated with laparoscopic colorectal surgery are essentially the same as those for open surgery. Certain other complications, such as port- site hernia, are specific to the laparoscopic approach. The overall rate of complications is approximately 11%. Ileus and small bowel obstruction are the most common causes for readmission (in about 4% of cases).24

In Table 2, we show the most frequent complications expected with respective time of occurrence.

Table 2. Complications

Table 2. Complications

Bowel Injury

Inadvertent bowel injuries may occur at any point in the procedure, but most commonly occur during extensive lysis of adhesions with either mishandling of the bowel or with excessive use of energy devices. Inadequate bowel preparation can also prevent adequate exposure, resulting in missed bowel injury.25

Virtually no energy source should be used within 1cm of the surface of the bowel. Additionally, a dissected or roughly handled section of bowel should be reexamined at the conclusion of a procedure looking for a possible injury.

Ureter Injury

A ureter may be injured because of failure of the surgeon to recognize the structure secondary to severity of the disease process, inadequate dissection techniques, or a lack of knowledge of anatomical relationships. No structure should be divided in the pelvis or near the pelvic brim without identification of the ureter along its entire course.

Ureter injuries are more commonly observed after sigmoid colon resection, low anterior resection, and abdominoperineal resection, but can be observed after right hemicolectomy. Ureter identification can be accomplished by identification of the iliac artery; the ureter will always cross over it. Ureter peristalsis will help differentiate the ureter from the gonadal vessels. The former will contract.26

The use of ureter stents will not prevent the injury but will certainly help with structure identification. Light stents can be used and might help in the identification of the ureter, but the laparoscopic light source should be attenuated to allow the intermittent light to be seen.

After the ureter has been injured, the first step is to recognize the injury and proceed with the laparoscopic repair if possible. The repair starts with the placement of a sitting suture to bring both ends together. After both ends are together, an end-to-end anastomosis is constructed with 3 or 4 interrupted 4/0 sutures, followed by placement of a JJ catheter and a Jackson-Pratt drain. If properly identified and repaired, ureter injuries have a very low morbidity rate.

Vascular Injuries

Major vascular injury during the initiation of pneumoperitoneum is a much-feared complication of laparoscopic procedures. Vascular injury is a major cause of death from laparoscopy, with a reported mortality rate of 15%. Major vascular injury can occur when the Veress needle is inserted prior to insufflation, or when a trocar is inserted after insufflation.

The reason for these injuries is the close proximity of the anterior abdominal wall to the retroperitoneal vascular structures. In thin people, this distance can be as little as 2cm. The distal aorta and right common iliac artery are particularly prone to injury. This is not surprising, given the fact that the take off of the right common iliac artery lies directly below the umbilicus.

Given the high risk of injury to a major vessel or bowel injury at the time of the first trocar insertion, we prefer to use a right or left upper quadrant approach whenever possible.7

Minor vascular injuries are named so because they are injuries to vessels of lesser importance than the aorta, inferior vena cava, and iliac vessels. It is not because these injuries are minor in nature. By far the most common minor vascular injury is to the inferior epigastric vessels. Injury to these vessels is reported to occur in up to 2.5% of laparoscopic hernia repairs. There were 76 cases of minor vascular injuries involving the epigastric vessels identified in a review of 10 837 patients undergoing hernia operation.27 Injuries of the epigastric vessels can be related to carelessness during the operative procedure. These injuries invariably occur during placement of secondary trocars, which should be placed under direct vision and with prior transillumination of the abdominal wall.

An endoloop should always be available and ready to use, because this can prevent the conversion of the procedure or can even be lifesaving.

Anastomotic Complications

Perhaps the most challenging procedures in surgery are those that include construction of an anastomosis, especially in colon and rectal surgery.28 Not only are these procedures technically demanding, but there is an ever present potential risk for anastomotic leak and stenosis. The success of these procedures is most often related to the technique used, but occasionally failure occurs even when excellence in technique is achieved. Of all the complications associated with colorectal surgery, the most devastating and constant, despite all techniques being performed properly is anastomotic leakage, which creates a significant increase in morbidity-mortality and frequently a permanent stoma.29 The reasons for this inevitable leakage are numerous but include bacterial count, preoperative radiation, chemotherapy, immunocompromised patients, malnutrition, and presence of co-morbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary artery disease. However, not uncommonly, a discrete cause is obscure. Multivariate analysis has shown that preoperative leukocytosis, intraoperative septic conditions, difficulties encountered during anastomosis, colo-colic anastomosis, low anastomosis, and postoperative blood transfusion are independent factors associated with increased anastomotic leak rates. A diverting ostomy can be a lifesaver in these patients.30

The recent use of anastomotic reinforcement has been associated with a decreased anastomotic leak rate.18

Wound-Related Problems

The 2 most common wound complications are infection and incisional hernia formation. Virtually both can be prevented with proper surgical technique and with the use of muscle splitting incisions.31 All 10-mm or larger trocar sites must be closed.

Port-site metastasis must be avoided by all means. With over 2000 laparoscopic colonic procedures, we have zero port-site metastasis. The steps we follow as a routine in all cases of laparoscopic colorectal cancer are (a) fixation of trocars to the abdominal wall, (b) avoidance of touching the tumor, (c) high vascular ligation, (d) intraoperative colonoscopy and intraluminal irrigation with 5% iodine povidone, (e) specimen isolation before extraction from the abdominal cavity, and (f) intraperitoneal and trocar-site irrigation with a tumoricide solution.

CONCLUSIONS

A laparoscopic approach for benign and malignant colon disease is safe, feasible, and effective. Although thorough understanding of anatomy and laparoscopic principles of surgery is mandatory, oncological principles must always be respected.32,33,34

There is a promising future in laparoscopic colorectal surgery, which will be enhanced by the development of new techniques to improve outcomes for the benefit of the patient. As surgery advances, patients will demand newer and less-invasive procedures.35

References

-

- American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons position statement on laparoscopic colectomy for curable cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:A1.

- Chen HH, Wexner SD, Weiss EG, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy for benign colorectal disease is associated with a significant reduction in disability as compared with laparotomy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1397-1400.

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina D, et al. Prospective comparison of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma: five-year results. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:S35-S46.

- Fowler DL, White SA. Laparoscopy-assisted sigmoid resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:183-188.

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Norem RF. Prospective evaluation of laparoscopic colon resection versus open colon resection for adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:811-816.

- Clinical Outcomes of surgical therapy Study Groups. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Eng J Med. 2004;350(20):2050-2059.

- Franklin ME, Ramos R, Rosenthal D, Schussler W. Laparoscopic colonic procedures. World J Surg. 1993;17:51-56.

- Monson JRT, Darzi A, Carey PD, Guillou PJ. Prospective evaluation of laparoscopic-assisted colectomy in an unselected group of patients. Lancet. 1992;340:831-833.

- Fielding GA, Lumley J, Nathanson L, Hewitt P, Rhodes M, Stitz R. Laparoscopic colectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:745-749.

- Bokey EL, Moore JWE, Keating JP, Zelas P, Chapius PH, Newland RC. Laparoscopic resection of the colon and rectum for cancer. Br J Surg. 1997;84:822-825.

- Wheeless CR Jr, Thompson BH. Laparoscopic sterilization. Review of 3600 Obstet Gynecol. 1973 Nov;42(5):751-758.

- Kockerling F, Schneider C, Reymond MA. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery study group (LCSSG). Early results of a prospective multicenter study on 500 consecutive cases of laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12: 37-41.

- Bergamaschi R, Arnaud JP. Intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis following laparoscopic left colon resection. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:800-801.

- Kockerling F, Reymond MA, Schneider C, et al, The Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery Study Group. Prospective multicenter study of the quality of oncologic resections in patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:963-970.

- Hellan M, Anderson C, Pigazzi A. Extracorporeal versus intracorporeal anastomosis for laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. JSLS. 2009;13:312-317.

- MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Handsewn vs. stapled anastomoses in colon and rectal surgery: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:180-189.

- Feingold DL, Addona T, Forde KA, et al. Safety and reliability of tattooing colorectal neoplasms prior to laparoscopic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:543- 546.

- Franklin ME Jr, Berghoff KE, Arellano PP, Trevino JM, Abrego-Medina D. Safety and efficacy of the use of bioabsorbable seamguard in colorectal surgery at the Texas Endosurgery Institute. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005 Feb;15(1):9-13.

- Phillips EH, Franklin M, Carroll BJ, Fallas MJ, Ramos R, Rosenthal Laparoscopic colectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;216:703-707.

- Greznlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J 2000;50:7-33.

- Laparoscopic surgery for stage III colon cancer: long-term follow-up. Surg 2000;14:612-616.

- Puente I, Sosa JL, Sleeman D, Desai U, Tranakas N, Hartmann R. Laparoscopic assisted colorectal surgery. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1994;4(1):1-7.

- Jacobs M, Verdeja G, Goldstein D. Minimally invasive colon resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:144-150.

- Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Seshadri PA, Cadeddu M, Gregoire R, Poulin EC. Defining a learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:217-222.

- Levy BS, Soderstrom RM, Dali DH. Bowel injuries during laparoscopy. Gross anatomy and histology. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:168.

- Stocchi L, Nelson H. Laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer: trial update. J Surg Onc. 1998;68:255-267.

- Khalili TM, Fleshner PR, Hiatt JR, et al. Colorectal cancer: comparison of laparoscopic with open approaches. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:832-838.

- Ulrich AB, Seiler C, Rahbari N, Weitz J, Buchler MW. Diverting stoma after low anterior resection: more arguments in favor. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Mar; 52(3):412- 418.

- Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, et al. Postoperative complications of laparoscopic-assisted colectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:119-122.

- Kockerling F, Rose J, Schneider C, et al, Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery Study Group (LCSSG). Laparoscopic colorectal anastomosis: risk of postoperative leakage: results of a multicenter study. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:639-644.

- Ziprin P et al. Ridgway PF, Peck DH, Darzi AW. The theories and realities of port- site metastases: a critical appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:395-408.

- Cohen SM, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer: the Cleveland Clinic Florida experience. Surg Oncol. 1993;2 (Suppl 1):35-42.

- Lord SA, Larach SW, Ferrara A, Williamson PR, Lago CP, Lube MW. Laparoscopic resections for colorectal carcinoma: a three-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:148-154.

- Whelan RL. Laparotomy, laparoscopy, cancer, and beyond. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:110-115.

- Dunker MS, Stiggelbout AM, van Hogezand RA, Ringers J, Griffioen G, Bemelman WA. Cosmesis and body image after laparoscopic-assisted and open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1334-1340.